Edward S Kraus, M.D.

- Professor of Medicine

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/profiles/results/directory/profile/0000620/edward-kraus

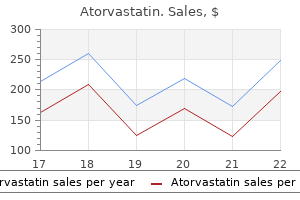

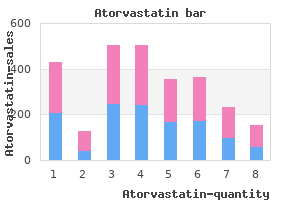

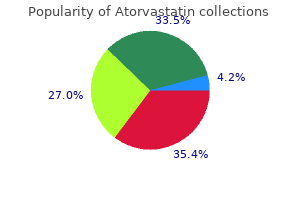

This was up from 17 percent in 2015 cholesterol and stress cheap atorvastatin 20mg with amex, assessment is a short medical evaluation for 549 549 16 percent in 2014 and 8 percent in 2011 cholesterol levels very low order 20 mg atorvastatin mastercard. What barriers to brief cognitive assessments exist cholesterol medication gout purchase atorvastatin, and how might they be overcome Knowledge of the overall usage cholesterol levels chart canada purchase atorvastatin 20mg line, procedures and outcomes of brief cognitive assessment in older adults is quite sparse cholesterol ratio of 1.9 purchase atorvastatin 40 mg fast delivery, and most of the limited data that does exist is at least a decade old cholesterol hdl levels purchase atorvastatin paypal. A22 were required to have practiced for at least 2 years, spend seniors are being assessed and just one in seven is getting at least half of their time in direct patient care, and have regular brief cognitive assessments. This number is in a practice in which at least 10 percent of their patients sharp contrast to the high percentages of seniors who are age 65 and older. A total of 1,954 provided by Medicare, but just one-third know that an individuals completed the survey by phone or online. Less than a third (28 percent) testing not definitive enough to make a diagnosis, instead have ever been assessed for cognitive problems. This view is consistent with recent data indicating that brief structured assessment In fact, just one in seven seniors (16 percent) receives instruments are imperfect tools and comprise just one regular cognitive assessments for problems with memory 557-558 aspect of the diagnostic process. Of those Cognitive Assessment Toolkit or the American who report performing brief cognitive assessments Academy of Family Physicians Cognitive Care Kit. For example, structured cognitive Of the 28 percent of seniors who report ever having assessment tools are incorrectly scored or reported in had a cognitive assessment, 89 percent say they were 561-562 one-quarter to one-third of cases. Additional sociodemographic risk factors such as race or sex concerns about the impact of a diagnosis on the patient, in deciding whether or not to assess a patient. Fifty-four percent also note that treatment Attitudes Toward Cognitive Assessment options are limited. Furthermore, believe that early detection of cognitive decline is mostly one in nine seniors (11 percent) say that these changes beneficial. A26 Only 2 percent of seniors believe that early interfere with their ability to function in activities such as detection of cognitive impairment is mostly harmful, cooking, getting dressed and grocery shopping. Forty and the top reasons focus on the negative psychological eight percent of seniors report doing activities or hobbies impact it may have. This contrasts with the 84 percent and early detection, a substantial minority (up to one who reported spending time doing activities that are third) also express concerns about assessment and beneficial for brain health in a 2006 telephone survey testing: 29 percent believe that tests for thinking or conducted by the American Society on Aging and the memory problems are unreliable; 24 percent agree MetLife Foundation of attitudes and awareness of brain 545 that the idea of all seniors being tested for thinking or health involving 1,000 adults age 42 and older. Among impairment, and 58 percent say it is very important those who have, 37 percent talked to their primary (Figure 16). Among the entire population of seniors impairment, and 87 percent consider it very important. Most 60 (54 percent) also say they try to make full use of their 50 benefits, getting all the tests, assessments and doctor visits available to them. Conversely, 46 percent say they 40 use their Medicare benefits only when they are having a 30 problem or need medical care. This represents an important opportunity is detected (61 percent versus 57 percent). With four of five seniors indicating dementia care experts with health care providers. Studies of these programs, in clinical trials or other forms of research as an important which involved small sample sizes, had mixed results. Food and Drug diagnosis and disclosure process in all care settings, Administration to assist clinicians in the diagnosis of particularly in primary care. As new diagnostic tools become available for clinical practice, physician and consumer attitudes and practices with respect to brief cognitive assessments may also evolve. Trends of Hope Despite significant challenges to improving brief cognitive assessments in the primary care setting, there are a number of encouraging signs that the United States is moving toward better and more numerous assessments, and better awareness of cognitive decline. Census Bureau 7,901 people from the Framingham Study who had survived report for July 2018. The model was updated by the Lewin Group in telephone usage; the second stage of this weight balanced January 2015 (updating previous model) and June 2015 the sample to estimated U. Detailed A weight for the caregiver sample accounted for the information on the model, its long-term projections and its increased likelihood of female and white respondents in methodology are available at alz. Sampling weights were also created of the data presented in this report, the following parameters of to account for the use of two supplemental list samples. The the model were changed relative to the methodology outlined at resulting interviews comprise a probability-based, nationally alz. This using the seasonally adjusted average prices for medical care is slightly lower than the total resulting from multiplying services from all urban consumers. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Report: these data come hours of unpaid care (18. A survey of 17,000 employees of a respondent if the beneficiary is not able to respond. Fifty-one percent had a primary medical specialty of Figures pertain only to Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older. Additional structured assessments used by primary care this question were accepted. Diagnosis of cognitive impairment may be stigmatizing (25 percent); Early diagnosis does not provide benefits (19 percent). One reason that the per-person costs estimated by for performing an assessment (21 percent); Follow-up care for Hurd and colleagues are lower than those reported in Facts diagnosed patients would strain primary care resources (17%). Lack of confidence or expertise: Disclosing results is difficult (44 percent); Specialists are better equipped to discuss A22. The survey was offered in English and Business Concerns: Lack of time during visits (40 percent); Spanish and as either an online Web survey or a phone survey. Follow-up care for diagnosed patients would strain primary care the 1,954 respondents had the following demographics: resources (24 percent); Lack of financial reimbursement for time 55 percent were female and 45 percent were male. Difficulties with Patients: percent were age 75 and older, 33 percent were age 65-69, and the patient refusal rate for follow up testing is high (44 percent); 26 percent were age 70-74. Thirty-eight percent resided in the Managing patients with cognitive impairment is difficult or time South, 22 percent in the West, 21 percent in the Midwest, and consuming (36 percent). Forty-two percent had an annual household income below $40,000, 30 percent had an income A26. Additional reasons seniors believe early diagnosis is important: between $40,000 and $74,999, and 28 percent had an income Additional responses, ranked by the percentage of participants above $75,000. Seventy-seven percent of respondents identified who selected that choice: It allows for earlier treatment of as white and non-Hispanic, 9 percent as black and non-Hispanic, symptoms with medication or other interventions (93 percent); and 8 percent as Hispanic. Seventy-six percent were retired, and A person can begin health measures to preserve existing cognitive 17 percent were working. The primary care physician survey was function for as long as possible (92 percent); It helps to understand conducted by Versta Research from December 10, 2018, through what is happening (91 percent); It allows the person and their family January 8, 2019. Of the 1,000 respondents, 68 percent spent less to plan for the future (91 percent); It allows the person to be tested than 90 percent of their professional time in direct patient care, and treated for reversible causes of thinking or memory problems while 32 percent spent between 90 and 100 percent of their (91 percent); It helps a person address potential safety issues time in direct patient care. On average, 49 percent of their ahead of time (90 percent); It encourages the person and his or patients were age 18-64 and 42 percent were age 65 and her family to seek support and education (89 percent); It allows for older. Thirty-two percent had been in practice for 15-24 years, more time to assemble medical and caregiving teams (83 percent); 31 percent for fewer than 15 years, 24 percent for 25-34 years, It relieves concerns about other things that might be wrong and 14 percent for 35 years or more. Eighty-four percent had (76 percent); It allows the person to participate in clinical trials and office-based practices, and 14 percent had hospital-based other research (71 percent). Participants were allowed to select more than one answer, so percentages do not add up to 100. Dement Geriatr Cogn analysis in young adults at genetic risk for autosomal dominant Disord Extra 2013;3:320-32. Brain disease, Lewy body, vascular and frontotemporal dementia, and 2009;132:1355-65. Stages of the neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 cognitive impairment. Introduction to the recommendations from of effectiveness from randomised controlled trials. Neuropathology of cognitively normal cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical elderly. Physical activity interventions in preventing cognitive Neurology 2009;72(17):1519-25.

Epilepsy is cholesterol and membrane fluidity order atorvastatin 10mg with visa, to a certain extent cholesterol ratio more important than total generic atorvastatin 40mg online, a problem of brain connectivity that results in cycles of neuronal activity that feed on themselves cholesterol test kit price generic 5 mg atorvastatin fast delivery. This surgical procedure interrupts the flow of currents in the brain and is a dramatic but effective way of putting paid to these cycles and nutrition cholesterol lowering foods buy cheap atorvastatin 10mg on-line, with them cholesterol ratio ldl hdl calculator order atorvastatin 40mg line, epilepsy cholesterol levels elevated buy atorvastatin once a day. What happens to the language, emotions and decisions of a body governed by two hemispheres that no longer communicate with each other Without the corpus callosum, the information available to one hemisphere cannot be accessed by the other. The right hemisphere only sees the left part of the world and also controls the left part of the body. Additionally, a few cognitive functions are fairly compartmentalized in each hemisphere. Typical cases are language (left hemisphere) and the ability to draw and represent an object in space (right hemisphere). So if patients with separated hemispheres are shown an object on the left side of their visual field, they can draw it but not name it. Conversely, an object to the right of their visual field is accessed by the left hemisphere and as such can be named but not really drawn. Imagine the following situation: patients with separated hemispheres are given an instruction in their left visual field; for example, that they will be paid money to lift up a bottle of water. Since it was presented to the left visual field, this instruction is only accessible to the right hemisphere. They put forth reasons, such as that they were thirsty or because they wanted to pour water for someone else. So the conscious mind acts not only as a front man but also as an interpreter, a narrator who creates a story to explain in hindsight our often inexplicable actions. Their way of putting free will in check is the show business equivalent of the project begun by Libet. Of course, the scientist does so using sleight of hand so that the switch is imperceptible. Again they resort to fiction; again our interpreters create a story in retrospect to explain the unknown course of events. In Buenos Aires, I set up, with my friend and colleague Andres Rieznik, a combination of magic and research to develop our own performiments, performances that are also experiments. Andres and I were investigating psychological forcing, a fundamental concept in magic that is almost the opposite of free will. It uses a set of precise tools to make spectators choose to see or do what the magician wants them to . In his book Freedom of Expression, the great Spanish magician Dani DaOrtiz explains exactly how the use of language, pacing and gaze allows magicians to make audience members do what they want them to . Approximately one second after a choice, the pupil dilates almost four times more when people choose the forced card. So our eyes are more reliable indicators of the true reasons behind a decision than our thoughts. These experiments deal with the old philosophical dilemma of responsibility and, to a certain extent, question the simplistic notion of free will. At this point we can only make conjectures about the answers to these questions, as Lavoisier did with his theory of the caloric. The prelude to consciousness We saw that the brain is capable of observing and monitoring its own processes in order to control them, inhibit them, shape them, halt them or simply manage them, and this gives rise to a loop that is the prelude to consciousness. Now we will see how three seemingly innocuous and mundane questions can help us to reveal and understand the origin of and reason for this loop, and its consequences. Charles Darwin, the great naturalist and father of contemporary biology, took on this question in depth and with rigour. His idea was that tickling only works if one is taken by surprise, and that unexpected factor disappears when we do it to ourselves. The detail that converted the game into science is the ability to change the intensity and delay in its action. When the tickler works with a scarce half-second delay, the tickling is felt as if someone else were doing it. When some time passes between our actions and their consequences, that produces a strangeness which makes them be * perceived as being performed by others. If our eyes are moving all the time, why is the image they construct in our brains still The stabilization of the image depends on two mechanisms that are now being tested out in digital cameras. The first is saccadic suppression; the brain literally stops recording when we are moving our eyes. This can be shown in a quick experiment at home: stop in front of a mirror and direct your gaze to one eye and then the other. That is the consequence of the microblindness that occurs in the exact moment that our eyes are moving. After a saccade, the image should move the way it does in home movies or in Dogme films, when the frame instantly shifts from one point in the image to another. That generates a smooth perceptive flow, in which the image remains static despite the frame constantly shifting. This is one of many examples of how our sensory apparatus reconfigures drastically according to the knowledge that the brain has of the actions it is going to carry out. Which is to say, the visual system is like an active camera that knows itself and changes its way of recording depending on how it is planning to move. While in a very different framework, this is the same idea that governs the impossibility of tickling ourselves. The brain foresees the movement it will make, and that warning creates a sensory change. In schizophrenia, this dialogue melds with reality in thoughts plagued with hallucinations. But if the same speech is played back and heard in a different context, it generates a cerebral response of greater magnitude. This difference is not observed in the auditory cortices of schizophrenics, whose brains do not distinguish when their voices are presented in real time or in a replay. How can someone perceive their inner mental conversations as if they were external voices Yet there is a space in which almost all of us make the same mistake, again and again: in dreams. They are also fictions created by our imagination, but dreams exercise their own sovereignty; it is difficult, almost impossible, for us to appropriate their stories. In some sense, then, dreams and schizophrenia have similarities, since they both revolve around not recognizing the authorship of * our own creations. In short: the circle of consciousness these three phenomena suggest a common starting point. In order to be able to stabilize the camera, in order to be able to recognize inner voices as its own. This mechanism is called efferent copy, and it is a way that the brain has of observing and monitoring itself. We have already seen that the brain is a source of unconscious processes, some of which are expressed in motor actions. Shortly before being carried out, they become visible to the brain itself, which identifies them as its own. A useful analogy here might be how, when a company decides to launch a new product, it lets its different departments know so that they can coordinate the process: marketing, sales, quality control, public relations, etc. For example, the purchasing group observes that there is less availability of some raw material and has to guess the reason because it is not aware of the new product launch. In the same way, due to the lack of internal information, the brain comes up with its idea of the most plausible scenario for explaining the state of things. It serves to convey the image of how delusions arise from a deficit in an internal communication protocol. But it sets a prerequisite of consciousness when it begins to inform itself of its own knowledge and its own states in a way that can be broadcast to different sections. However, this discussion may become less rhetorical and more concrete in the near future, when we build machines that can express all the features of consciousness. The physiology of awareness We live in unprecedented times, in which the factory of thoughts has lost its opacity and is observable in real time. In one case we consciously recognize the stimulus: we can talk about it and report on it. Sensory information arrives, for example, in the form of light to the retina, and turns into electrical and chemical activity that spreads through the axons to the thalamus, in the very centre of the brain. From there, the electrical activity spreads to the primary visual cortex, located in the back of the brain, near the nape. This delay is not only due to the conduction times in the brain but also to the construction of a cerebral state that codifies the stimulus.

20 mg atorvastatin amex. Long Live la Cholesterol.

Close inspection reveals cholesterol test fasting or not cheap atorvastatin 40mg with mastercard, however cholesterol foods to lower generic 20mg atorvastatin with visa, that at the level of their microstructure total cholesterol lowering foods cheap atorvastatin 10 mg otc, shared features are present both within and between repertoires (gure 3 usda cholesterol in eggs buy atorvastatin 10 mg with mastercard. Each song in the repertoire contains phrases drawn from a large pool that recur again and again cholesterol content of foods buy atorvastatin 10 mg visa, but in each song type they are arranged in a different sequence definition du cholesterol generic atorvastatin 5 mg without a prescription. Evidently what happens when a young male learns to sing is that he acquires a set of songs from the adults he hears and breaks them down into phrases or segments. He then creates variety and enlarges his repertoire by rearranging these phrases or segments in different patterns. Two sections are marked with dots and arrows to illustrate sharing of large segments between songs, clearly the result of recom bining sections of learned songs during development. Some of the most complex songs of all are found in birds that, as they acquire and develop their repertoire, take this process to extreme. Mock ingbirds and their relatives create hundreds of distinctive sequences using phrases that are both invented and acquired not only from their own species, but from other species as well, all recast into mockingbird form and tempo (Boughey and Thompson 1976; Baylis 1982). The record is held by a male brown thrasher, a relative of the mockingbird, with an individual repertoire of over 1,000 distinct songs (Kroodsma and Parker 1977). At some primitive level, the accomplishments of these songsters are reminiscent of our own speech behavior. The more accomplished song birds create huge vocal repertoires, making extensive use of the same basic process of syntactical recombination or phonocoding that we use to create words. Song sequences are not meaningfully distinct, in the referen tial sense; they are rich in affective content, but lacking in symbolic content. Each of the thousands of winter wren songs that exist means basically the same thing. Each serves as a kind of badge or emblem, a sign that denotes identity, population membership, and social status. Such functions are important enough from a communicative point of view, and there may be others. Many wood warblers have two distinct classes of songs, one associated more with sex and the other more with male-to male interactions and aggression, as though there is a contrast in the quality or nature of the underlying emotional state (Kroodsma 1988). But as far as I know, no one has suggested that they are in any way sym bolically distinct. The variety introduced by the generation of repertoires serves not to enrich meaning but to create sensory diversity. We could think of repertoires as providing aesthetic enjoyment or as alleviating boredom in singer and listener. But in these learned birdsongs, phonocoding does not augment the knowledge conveyed, in the symbolic sense, as is so obviously the case in our own speech behavior. On the other hand, symbolic functions are less at issue in music, and something like phonological syntax is also involved in musical composition. Could it be that more parallels with music than with language are to be found in the communicative behavior of animals If it is at all true that phonocoding in animals has some relationship, however remote, to the creation of human music, where in the animal kingdom should the search begin The potential for the unusually rich exploitation of phonological syntax that generates the wonderfully diverse sound patterns of birdsong seems to depend in turn on their learnability. Phonocoding does occur in innate songs of both birds and mammals (Craig 1943; Robinson 1979, 1984), but never on the elaborate scale that we nd in some learned birdsongs. The only other case in which something remotely similar is to be found in animals is in the learned songs of the humpback whale (Payne,Tyack, and Payne 1983; Payne and Payne 1985). Note that the only animal taxa for which we know for sure that vocal learning shapes the development of naturally occurring vocal behavior are birds and cetaceans. With the possible exception of bats (Boughman 1998), other animals, including nonhuman primates, have vocal repertoires that are innate. We can infer that the ability to learn new vocalizations, evident in no primate other than humans (Snowdon and Elowson 1992), greatly facilitated the emergence and rich exploita tion of phonocoding, employed subsequently as a basic step in the evo lution of speech behavior. On this basis I would argue that human music may have predated the emergence of language (see chapter 1 and Merker, this volume). What gave the human brain the capacity for lan guage was more than the ability to learn and produce new sounds in an in nite number of combinations. Much more remarkable was the com pletely novel ability of our immediate ancestors to attach new meanings to these sounds and recombine them into a multitude of meaningful sen tences, something that no other organism has achieved. So if what birds and whales can tell us about the evolution of language is so limited, it is not unreasonable to wonder if they have more to say about the origins of music. The fact that many animal calls are fundamentally affective and non symbolic augurs well for the prospect of some kind of commonality between those sounds and music. Both are immensely rich in emotional meaning, but generally speaking, neither animal song nor, except in very special cases, human music is usually viewed as meaningful in the strict, referential, symbolic sense. So rather than referential alarm and food calls of animals, we would be more likely to gravitate to animal songs if we were looking for roots for human music. I focus here on one basic theme, namely, creativity, which I take to be a fundamental requirement for the origins of music. Adopting once more a reductionistic stance, I 42 Peter Marler concentrate on one ingredient of the creative aspect of music, essential for composers, performers, and other makers of music, and for those who delight in listening to music performed by others: the ability to create acoustic novelty. Both chim panzees and gibbons are close relatives of humans, and vocalizations of both are considered as protomusical (Wallin 1991). I will make no effort to review their entire repertoires, which are well documented (Goodall 1986; Mitani 1994; Marler and Tenaza 1977; Geissmann 1993). This is a loud, rhyth mical hooting, typically about ten seconds in duration, beginning softly and working up to an almost screamlike climax (Goodall 1986; Marler and Hobbett 1975). As recorded from different individuals and from the same individual in different circumstances, variation is substantial, but typically consists of four parts: introduction, build-up, climax, and let down. One pant-hoot includes anything from fteen to thirty distinct sounds, characterized as hoots, screams, and whimpers, some on pro duced on inhalation, some on exhalation. Rather like birdsong, it is used as an affective, nonsymbolic display in many different situations, especially during intergroup encoun ters, when excited, after prey capture, to assert dominance, and, often in chorus, to keep in touch in the forest (Goodall 1986). The key point here is that, despite variations, each individual chimp always pant-hoots in Fig. Variation is considerable and probably meaningful, but it is always based on a single modal form. As far as I know, no one in the eld who has studied the behavior of chimpanzees, in the wild or in captivity, ever hinted at the possibility that an individual chimpanzee has a reper toire of several consistently distinct patterns of pant-hooting. Again, this is an emotive, nonsymbolic signal used in dif ferent forms by both sexes for locating each other in the forest and for maintaining territories (Tenaza 1976; Geissmann 1993). As with chim panzee pant-hooting, a lot of variation exists, but each individual has its own distinctive, modal song pattern (gure 3. As far as I know, there is no recorded case from any of the ten species of gibbons of an indi vidual repertoire of more than one basic song type, although several gibbons perform interesting male-female duets (Lamprecht 1970; Geiss mann 1993). In both chimpanzees and gibbons the basic patterning of these complex calls appears to be innate, and develops normally in social isolation and, as Geissmann (1993) showed in gibbons, in intermediate or mixed form in hybrids. These elaborate and highly individualistic sequences of patterned sounds, although clearly candidates for consideration as animal songs, are quite constrained from an acoustic point of view. Each individual has one fundamental modal pattern, stable over long periods of time, around which all of its variants are grouped. This is a much more complex pattern, more elaborate than anything that an ape ever produced. These are assembled during develop ment as a collage of learned phrases and notes, in a number of different, set sequences, to create the repertoire of multiple song types (Kroodsma 1980; Kroodsma and Momose 1991). How does this compare with the songs of gibbons and the pant hooting of chimpanzees They are all affective, nonreferential displays, given in a state of high arousal, and used especially for achieving and modu lating social contact and spacing. They are all highly individualistic, within limitations imposed by phonocoding rules that prevail in each species. Ape song reper toires are limited to one pattern per animal, supplemented by a range of Fig. Each male has a reper toire of maybe ten song types and the winter wren is only a beginner as wrens go; other wren species have repertoires numbered in the hundreds (Kroodsma and Verner 1978). Some songbirds with learned songs have individual repertoires that are huge; repertoires of monkeys and apes are strictly limited. If we examine the way in which large birdsong repertoires develop, we nd an ontogenetic principle operating that is either feeble or simply lacking in nonhuman primates. Songbirds, with their learned songs, have a developmental strat egy with all the hallmarks of a truly creative process. As far as I know, phonocoding with this degree of richness has never been recorded in any animal with innate vocalizations. In a classic manifestation of phonolog ical syntax, wrens and other songbirds display a remarkable ability to rearrange learned phrases, seemingly doing so almost endlessly in some species. Many different sequences are created, generating, in effect, a kind of animal music. The sequences are not random but orderly, orga nized by de nable rules and structured in such a way as to yield many stable, repeatable, distinctive patterns, the precise number varying from species to species and bird to bird. Together with whale songs, also learned (Payne, Tyack, and Payne 1983; Payne, this volume), these bird songs are an obvious place to look for insights into what underlying aes thetic principles, if any, are shared between animal and human music. I draw two modest conclusions from this overview of animal commu nication, language and music. From a reductionistic point of view, a convenient basis for animal-human comparisons is provided by the realization that the potential for phonocoding is a critical requisite for the emergence not only of speech and language but also of music. I suggest that we can already see a version of such a process in operation, albeit in primordial form, in some learned songs of animals, especially songbirds. An obvious next step would be to analyze phonocoding rules that birds use when they sing. A minimalist de nition of music, at least of the Western, tonal variety, might be couched in terms of notes with speci c pitches, intervals, and distinctive timbres combined into phrases that are repeated with additions and deletions, assembled into series with a par ticular meter and rhythm, and so constituting a song or melody. One approach to the human-animal comparison would be to see whether any animal sounds conform to similar taxonomic criteria, all of which are potentially studiable in animals. Are correlations seen among lifestyle, tempera ment, and song tempo in different bird species It is my conviction that 46 Peter Marler the vocal behavior of birds will prove to be as pro table to study as that of our much closer relatives, monkeys and apes, as we explore them for insights into the origins of music. Food-elicited vocalizations in golden lion tamarins: Design features for representational communication. The relation between food preference and food-elicited vocalizations in golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rasalia). Species speci city and individual variation in the songs of the brown trasher (Toxostoma rufum) and catbird (Dumetella carolinensis). The vocal repertoire of the red junglefowl: A spectrographic classi cation and the code of communication. Toque macaque food calls:Semantic communication concerning food dis tribution in the environment. Food-calling and audience effects in male chickens,Gallus gallus: Their relationships to food availability, courtship and social facilitation. Food calling in the domestic fowl (Gallus gallus):The role of external referents and deception. Semantics of an avian alarm call system:The male domestic fowl: Gallus domesticus. Song types and their use: Developmental exibility of the male Blue-winged Warbler. Does a sender communicate information about the quality of a food referent to a receiver Species-universal microstructure in the learned song of the swamp sparrow (Melospiza georgiana). Progressive changes in the songs of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae):A detailed analysis of two seasons in Hawaii. An analysis of the organization of vocal communication in the titi monkey Callicebus moloch. Syntactic structures in the vocalizations of wedge-capped capuchin monkey, Cebus nigrivittatus. Vocalizations in response to predators in three species of Malaysian Callosciurus (Sciuridae). Biomusicology: Neurophysiological, Neuropsychological and Evolutionary Perspectives on the Origins and Purposes of Music.

Enco ura ge mo the rto co ntinue M usculo s eleta l system bre a st dingsinc thiswillhe lp to o ve rco me the o bstructio n le cholesterol definition order generic atorvastatin. W ha this sta the ca n cer Thisisusua lly a na de no ca rcino ma tha ta riss f ro m the pe riphe ra lzo ne o f the pro sta t gla nd cholesterol medication niacin cheap atorvastatin 10 mg fast delivery. S inusve no sus S mo o th pa rto f righta trium; M P The ea r t E xa m les fdefects co ro na ry sinuso blique ve ino f l ta trium cholesterol in food bad discount atorvastatin 20mg overnight delivery. Tr ea t en t the re isno spe ciictre a tme nt o rthisdisa s P re dniso lo ne a ndcre a tinine re pla c me ntma y be co nside re d cholesterol levels equivalent atorvastatin 10mg low price. P a tintwillbe whe lcha irbo unda t~1 ye a rsre rto o ccupa tio na lthe ra py a ndphysio the ra py cholesterol ratio of 2.9 buy atorvastatin 20mg with amex. Thisisa ra re X linke dre c ssive diso rde rtha tca ussa build up o urica cidinthe bo dy cholesterol food chart 40 mg atorvastatin otc. Thisisa ne uro de ve lo pme nta ldiso rde ro f bra ingre y ma ttr Thisisa nX linke dre c ssive co nditio ninwhich the re ispa rtia lo r a co mpl t a bsnc o the co rpusca llo sum. R rra lto spe ch a ndla ngua ge I vestiga ti s the ra py, ne uro psycho lo gistne uro lo gy a ndphysio the ra py. Tre a tco mo rbiditissuch a sde pre ssio n, S ign sa n d sym t s which isco mmo ninthisgro up. Thisco nditio nca ussno nma ligna nttumo ursto gro w ina va rity o o rga ns Thisisa diso rde ro co nne ctive tissue due to a bno rma l ibrillin o rma tio n. Thisisa na uto so ma lre c ssive co nditio ntha tca ussne ura l Thisisa na uto so ma lre c ssive disa s inwhich l ve lso f de ge ne ra tio n. U L A he rnia isthe pro trusio no f a viscus Typ es o rpa rto f a viscusthro ugh a we a ke ning the re a re two type so inguina lhe rnia: initsco nta iningca vity. H T U L Typ es a uses the re a re two type so f hia tushe rnia: slidinga ndro lling. Over 100 maps are organised by body system, with a concluding section of miscellaneous examples. Both works gave expression to long-standing curiosity on the part of a musicologist regarding what light modern neuroscience might shed on questions such as the origins, evolutionary development, and purposes of music, questions that he felt were incompletely dealt with by his dis cipline. Ever since his student days, this musicologist had been on a quest for a musicological paradigm to complement traditional approaches. Since the Second World War, and more particularly in recent decades, the neurosciences and behavioral biology have made signi cant strides in areas relevant to the foundations of musicology. One result of this was the creation of the Foundation for Biomusicology and Acoustic Ethology, with its executive organ the Institute for Biomusicology, in March 1995. The Institute is located in the town of Ostersund, situated close to the geographic midpoint of Scandinavia. As part of its efforts to stimulate biomusicological research, the Institute sketched a series of international workshops to be held in Flo rence, Italy, a place where in the late sixteenth century the scholastically oriented music theory of the Middle Ages started to give way to more empirically oriented musicology, represented among others by Vincenzo Galilei, the father of Galileo Galilei. These Florentine Workshops in x Preface Biomusicology were to deal with the origins (phylogeny) of music, with its ontogeny, and with the interaction of biology and culture in music, respectively. We have the pleasure of thanking all contributors, including those who were not with us in person in Florence, for their great interest in and commitment to the topics and issues of the workshop, questions that for the greater part of this century have been discussed only rarely, and never before in a framework of joint discussions among representatives of most of the disciplines that reasonably can be expected to have some thing to contribute to the elucidation of the evolutionary history and biological roots of music. Almeida of its editorial staff for their interest and efforts in making these studies available to an international audience. Frayer and Social Evolution Department of Anthropology University College London University of Kansas London, England Lawrence, Kansas Jean Molino Walter Freeman Ecublens, Switzerland Division of Neurobiology Bruno Nettl University of California University of Illinois at Urbana Berkeley, California Champaign Thomas Geissmann Urbana, Illinois Institute of Zoology Chris Nicolay Tieraerzliche Hochschule Department of Anthropology Hannover Kent State University Hannover, Germany Kent, Ohio Marc D. Hauser Bruce Richman Departments of Psychology and Cleveland Heights, Ohio Anthropology Katharine Payne Harvard University Bioacoustic Research Program Cambridge, Massachusetts Cornell Laboratory of Michel Imberty Ornithology Department of Psychology Ithaca, New York Universite de Paris X Peter J. Slater Nanterre, France School of Environemental and Harry Jerison Evolutionary Biology Department of Psychiatry and University of St. Wallin Abstract In this introduction to the new eld of evolutionary musicology, we see that the study of music origins provides a fresh and exciting approach to the under standing of human evolution, a topic that so far has been dominated by a focus on language evolution. The language-centered view of humanity has to be expanded to include music, rst,because the evolution of language is highly inter twined with the evolution of music, and, second, because music provides a spe ci c and direct means of exploring the evolution of human social structure, group function, and cultural behavior. Music making is the quintessential human cul tural activity, and music is an ubiquitous element in all cultures large and small. The study of music evolution promises to shed light on such important issues as evolution of the hominid vocal tract; the structure of acoustic-communication signals; human group structure; division of labor at the group level; the capacity for designing and using tools; symbolic gesturing; localization and lateralization of brain function; melody and rhythm in speech; the phrase-structure of lan guage; parent-infant communication; emotional and behavioral manipulation through sound; interpersonal bonding and synchronization mechanisms; self expression and catharsis; creativity and aesthetic expression; the human af nity for the spiritual and the mystical; and nally, of course, the universal human attachment to music itself. Music Origins and Human Origins What is music and what are its evolutionary origins Such questions were the among the principal areas of investigation of the members of the Berlin school of comparative musicology of the rst half of the twentieth century, as represented by such great gures as Carl Stumpf, Robert Lach, Erich von Hornbostel, Otto Abraham, Curt Sachs, and Marius Schneider. How this came to pass entails a long and very political history, one that has as much to do with rejection of racialist notions present in much European schol arship in the social sciences before the Second World War as with the rise of the cultural-anthropological approach to musicology in America during the postwar period. Musicology did not seem to need an of cial decree, like the famous ban on discussions of language origin by the Societe de Linguistique de Paris in 1866, to make the topic of music origins unfashionable among musicologists. And with that, musicology seemed to relinquish its role as a con tributor to the study human origins as well as any commitment to devel oping a general theory of music. The current volume represents a long-overdue renaissance of the topic of music origins. If its essays suggest nothing else, it is that music and musical behavior can no longer be ignored in a consideration of human evolution. Music offers important insight into the study of human origins and human history in at least three principal areas. First, it is a universal and multifunctional cultural behavior, and no account of human evolution is complete without an understanding of how music and dance rituals evolved. Even the most cursory glance at life in tradi tional cultures is suf cient to demonstrate that music and dance are essential components of most social behaviors, everything from hunting and herding to story telling and playing; from washing and eating to praying and meditating; and from courting and marrying to healing and burying. Therefore the study of music origins is central to the evolu tionary study of human cultural behavior generally. Second, to the extent that language evolution is now viewed as being a central issue in the study of human evolution, parallel consideration of music will assume a role of emerging importance in the investigation of this issue as it becomes increasingly apparent that music and language share many underlying features. Therefore, the study of language evolu tion has much to gain from a joint consideration of music. This includes such important issues as evolution of the human vocal tract, the hominid brain expansion, human brain asymmetry, lateralization of cognitive function, the evolution of syntax, evolution of symbolic gesturing, and the many parallel neural and cognitive mechanisms that appear to under lie music and language processing. Third, music has much to contribute to a study of human migration patterns and the history of cultural contacts. In the same way that genes and languages have been used successfully as markers for human migra tions (Cavalli-Sforza, Menozzi, and Piazza 1994), so too music has great potential to serve as a hitherto untapped source of information for the study of human evolution. This is because musics have the capacity to blend and therefore to retain stable traces of cultural contact in a way that languages do only inef ciently; languages tend to undergo total replacement rather than blending after cultural contact, and thus tend to lose remnants of cultural interaction. In summary, these three issues, the universality and multifunctionality of music, the intimate relationship between music evolution and language evolution, and the potential of music to shed light on patterns of cultural interaction, are important applications of evolutionary musicology to the study of human origins and human culture. Evolutionary musicology deals with the evolutionary origins of music, both in terms of a comparative approach to vocal communication in animals and in terms of an evolutionary psychological approach to the emergence of music in the hominid line. Neuromusicology deals with the nature and evolution of the neural and cognitive mechanisms involved in musical production and perception, as well as with ontogenetic devel opment of musical capacity and musical behavior from the fetal stage through to old age. Comparative musicology deals with the diverse func tional roles and uses of music in all human cultures, including the con texts and contents of musical rituals, the advantages and costs of music making, and the comparative features of musical systems, forms, and per formance styles throughout the world. This eld not only resuscitates the long-neglected concept of musical universals but takes full advantage of current developments in Darwinian anthropology (Durham 1991), evo lutionary psychology (Barkow, Cosmides, and Tooby 1992), and gene culture coevolutionary theory (Lumsden and Wilson 1981; Feldman and Fig. It comprises three principal branches, as described in the text: evolutionary musicology, neuromusicology, and comparative musicology. The synthetic questions that evolutionary musicology (the subject of this volume) addresses incorporate all three branches, as elab orated in the rest of the chapter. Not shown in the gure is a series of more practical con cerns that fall under the purview of applied biomusicology (see text). Wallin Laland 1996) in analyzing musical behavior from the standpoint of both natural selection forces and cultural selection forces. To complete this picture of biomusicology, it is important to point out that each of these three major branches has practical aspects that con tribute to what could be referred to as applied biomusicology, which attempts to provide biological insight into such things as the therapeutic uses of music in medical and psychological treatment; widespread use of music in the audiovisual media such as lm and television; the ubiqui tous presence of music in public places and its role in in uencing mass behavior; and the potential use of music to function as a general enhancer of learning. The theme of the current volume falls within the evolutionary musi cology branch of biomusicology. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to providing an overview of the major issues and methods of evolution ary musicology. To those who are coming across these ideas for the rst time (which, we suspect, is most readers), our overall message is quite simple: it is time to take music seriously as an essential and abundant source of information about human nature, human evolution, and human cultural history. Major Issues in Evolutionary Musicology this section presents some of the major topics in evolutionary musicol ogy. It serves as an overview of these topics, allowing ensuing chapters to provide detailed theoretical perspectives on them. For every structural feature that can be claimed as being a de ning feature of music, one can always nd (or dream up) a musical style that lacks this property.

References

- Bharati S, Lev M: Embryology of the heart and great vessels. In: Mavroudis C, Backer CL (eds): Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. St Louis, CV Mosby, 1994, pp 1-Gow RM, Hamilton RM: Developmental biology of specialized conduction tissue. In: Freedom RM, Benson LN, Smallhorn JF (eds): Neonatal Heart Disease. London, Springer-Verlag, 1992, pp 65-Walls EW: The development of the specialized conducting tissue of the human heart. J Anat 1947; 81:93-00.

- Micali, S., Silver, R.I., Kaufman, H.S. et al. Measurement of urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase to assess renal ischemia during laparoscopic operations. Surg Endosc 1999;13:503-506.

- Lown B, Perlroth MG, Kaidbey S, et al: Cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 269:325-331, 1963.

- Cervigni M: Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and glycosaminoglycans replacement therapy, Transl Androl Urol 4(6):638n642, 2015.