Simon G. Stacey

- Consultant Anaesthetist & Intensivist, Bart's Heart Centre, Bart's and The London NHS Trust, London, UK

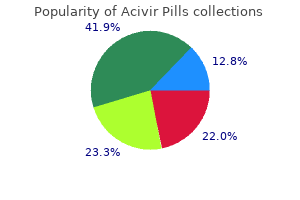

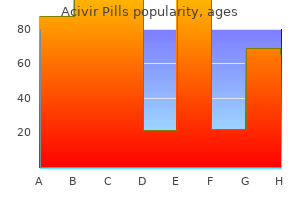

The preceding inequality states that the sum is increased by evidence that is more compatible with the hypotheses under study hiv aids infection process 200 mg acivir pills mastercard. It is noteworthy that enhancement suggests that people are inappropriately responsive to the prior probability of the data viral anti-gay protester dies order acivir pills from india, whereas base-rate neglect indicates that people are not sufficiently responsive to the prior probability of the hypotheses hiv infection rate namibia buy acivir pills 200mg lowest price. The following schematic example illustrates an implication of enhancement and compares it with other models hiv infection rate united states purchase acivir pills online. In the absence of any specific evidence hiv infection via eye 200 mg acivir pills for sale, assume that all suspects are considered about equally likely to have committed the crime hiv infection rate by country cheap acivir pills 200mg with amex. Suppose further that a preliminary investigation has uncovered a body of evidence. According to the Bayesian model, the probabilities of all of the suspects remain unchanged because the new evidence is nondiagnostic. However, the probability that the murder was committed by a particular suspect (rather than by any of the others) is expected to increase with the amount of evidence. For this reason, we first describe several new studies that have tested both parts of the unpacking principle within the same experiment, and then we review previous research that provided the impetus for the present theory. We asked Stanford undergraduates (N= 120) to assess the likelihood of various possible causes of death. The subjects were informed that each year approximately 2 million people in the United States (nearly 1% of the population) die from different causes, and they were asked to estimate the probability of death from a variety of causes. Half of the subjects considered a single person who had died recently and assessed the probability that he or she had died from each in a list of specified causes. They were asked to assume that the person in question had been randomly selected from the set of people who had died the previous year. The other half, given a frequency judgment task, assessed the percentage of the 2 million deaths in the previous year attributable to each cause. In each group, half of the subjects were promised that the five most accurate subjects would receive $20 each. Each subject evaluated one of two different lists of causes, constructed such that he or she evaluated either an implicit hypothesis. Each type had three components, one of which was further divided into seven subcomponents. To avoid very small probabilities, we conditioned these seven subcomponents on the corresponding type of death. To provide subjects with some anchors, we informed them that the probability or frequency of death resulting from respiratory illness is about 7. Mean Probability and Frequency Estimates for Causes of Death in Study 1: Comparing Evaluations of Explicit Disjunctions with Coextensional Implicit Disjunctions Note: Actual percentages were taken from the 1990 U. Specifically, the former equals 58%, whereas the latter equals 22% + 18% + 33% = 73%. This index, called the unpacking factor, can be computed directly from probability judgments, unlike w, which is defined in terms of the support function. Subadditivity is indicated by an unpacking factor greater than 1 and a value of wless than 1. It is noteworthy that subadditivity, by itself, does not imply that explicit hypotheses are overestimated or that implicit hypotheses are underestimated relative to an appropriate objective criterion. An analysis of medians rather than means revealed a similar pattern, with somewhat smaller differences between packed and unpacked versions. Comparison of probability and frequency tasks showed, as expected, that subjects gave higher and thus more subadditive estimates when judging probabilities than when judging frequencies, F (12, 101) = 2. The judgments generally overestimated the actual values, obtained from the 1990 U. The only clear exception was heart disease, which had an actual probability of 34% but received a mean judgment of 20%. Because subjects produced higher judgments of probability than of frequency, the former exhibited greater overestimation of the actual values, but the correlation between the estimated and actual values (computed separately for each subject) revealed no difference between the two tasks. The following design provides a more stringent test of support theory and compares it with alternative models of belief. Suppose A1, A2, and B are mutually exclusive and exhaustive; A = (A1 A2);A is implicit; and A is the negation of A. Consider the following observable values: Different models of belief imply different orderings of these values: support theory, = Bayesian model, = = = belief function, = = regressive model, = =. Support theory predicts and due to the unpacking of the focal and residual hypotheses, respectively; it also predicts = due to the additivity of explicit disjunctions. The Bayesian model implies = and =, by extensionality, and =, by additivity. The observation that < could also be explained by a regressive model that assumes that probability judgments satisfy extensionality but are biased toward. However, this model predicts no difference between and, each of which consists of a single judgment, or between and, each of which consists of two. Thus, support theory and the regressive model make different predictions about the source of the difference between and. To contrast these predictions, we asked different groups (of 25 to 30 subjects each) to assess the probability of various unnatural causes of death. All subjects were told that a person had been randomly selected from the set of people who had died the previous year from an unnatural cause. The hypotheses under study and the corresponding probability judgments are summarized in Table 25. The first row, for example, presents the judged probability that death was caused by an accident or a homicide rather than by some other unnatural cause. In accord with support theory, = 1 + 2 was significantly greater than = 1 + 2, p <. Before turning to additional demonstrations of unpacking, we discuss some methodological questions regarding the elicitation of probability judgments. It could be argued that asking a subject to evaluate a specific hypothesis conveys a subtle (or not so subtle) suggestion that the hypothesis is quite probable. Subjects, therefore, might treat the fact that the hypothesis has been brought to their attention as information about its probability. To address this objection, we devised a task in which the assigned hypotheses carried no information so that any observed subadditivity could not be attributed to experimental suggestion. Subjects were asked to write down the last digit of their telephone numbers and then to evaluate the percentage of couples having exactly that many children. They were promised that the three most accurate respondents would be awarded $10 each. As predicted, the total percentage attributed to the numbers 0 through 9 (when added across different groups of subjects) greatly exceeded 1. Thus, subadditivity was very much in evidence, even when the selection of focal hypothesis was hardly informative. Subjects overestimated the percentage of couples in all categories, except for childless couples, and the discrepancy between the estimated and the actual percentages was greatest for the modal couple with 2 children. Furthermore, the sum of the probabilities for 0, 1, 2, and 3 children, each of which exceeded. The observed subadditivity, therefore, cannot be explained merely by a tendency to overestimate very small probabilities. In sharp contrast to the subadditivity observed earlier, the estimates for complementary pairs of events were roughly additive, as implied by support theory. The finding of binary complementarity is of special interest because it excludes an alternative explanation of subadditivity according to which the evaluation of evidence is biased in favor of the focal hypothesis. Subadditivity in Expert Judgments Is subadditivity confined to novices, or does it also hold for experts. Redelmeier, Koehler, Liberman, and Tversky (1995) explored this question in the context of medical judgments. They presented physicians at Stanford University (N= 59) with a detailed scenario concerning a woman who reported to the emergency room with abdominal pain. Half of the respondents were asked to assign probabilities to two specified diagnoses (gastroenteritis and ectopic pregnancy) and a residual category (none of the above); the other half assigned probabilities to five specified diagnoses (including the two presented in the other condition) and a residual category (none of the above). Subjects were instructed to give probabilities that summed to one because the possibilities under consideration were mutually exclusive and exhaustive. Consistent with the predictions of support theory, however, the judged probability of the residual in the two diagnosis condition (mean =. One scenario, for example, concerned a 67-year-old man who arrived in the emergency room suffering a heart attack that had begun several hours earlier. Each physician was asked to assess the probability of one of the following four hypotheses: patient dies during this hospital admission (A); patient is discharged alive but dies within 1 year (B); patient lives more than 1 but less than 10 years (C); or patient lives more than 10 years (D). Throughout this chapter, we refer to these aselementary judgments because they pit an elementary hypothesis against its complement, which is an implicit disjunction of all of the remaining elementary hypotheses. After assessing one of these four hypotheses, all respondents assessed P(A, B), P(B, C), and P(C, D) or the complementary set. We refer to these as binary judgments because they involve a comparison of two elementary hypotheses. The means of the four groups in the preceding example were 14% for A, 26% for B, 55% for C, and 69% for D, all of which overestimated the actual values reported in the medical literature. In problems like this, when individual components of a partition are evaluated against the residual, the denominator of the unpacking factor is taken to be 1; thus, the unpacking factor is simply the total probability assigned to the components (summed over different groups of subjects). In sharp contrast, the binary judgments (produced by two different groups of physicians) exhibited near-perfect additivity, with a mean total of 100. Further evidence for subadditivity in expert judgment has been provided by Fox, Rogers, and Tversky (1996), who investigated 32 professional options traders at the Pacific Stock Exchange. These traders made probability judgments regarding the closing price of Microsoft stock on a given future date. Microsoft stock is traded at the Pacific Stock Exchange, and the traders are commonly concerned with the prediction of its future value. Nevertheless, their judgments exhibited the predicted pattern of subadditivity and binary complementarity. Subadditivity in expert judgments has been documented in other domains by Fischhoff et al. Review of Previous Research We next review other studies that have provided tests of support theory. Tversky and Fox (1994) asked subjects to assign probabilities to various intervals in which an uncertain quantity might fall, such as the margin of victory in the upcoming Super Bowl or the change in the Dow Jones Industrial Average over the next week. Further evidence for binary complementarity comes from an extensive study conducted by Wallsten, Budescu, and Zwick (1992), who presented subjects with 300 propositions concerning world history and geography. True and false (complementary) versions of each proposition were presented on different days. We next present a brief summary of the major findings and list both current and previous studies supporting each conclusion. Unpacking an implicit hypothesis into its component hypotheses increases its total judged probability, yielding subadditive judgments. For each experiment, the probability assigned to the implicit hypothesis and the total probability assigned to its components in the explicit disjunction are listed along with the resulting unpacking factor. All of the listed studies used an experimental design in which the implicit disjunction and the components of the explicit disjunction were evaluated independently, either by separate groups of subjects or by the same subjects but with a substantial number of intervening judgments. The probabilities are listed as a function of the number of components in the explicit disjunction and are collapsed over all other independent variables. Results of Experiments Using Qualitative Hypotheses: Average Probability Assigned to Coextensional Implicit and Explicit Disjunctions and the Unpacking Factor Measuring the Degree of Subadditivity Note: the number of components in the explicit disjunction is denoted by n. The fact that subadditivity is observed both for qualitative and for quantitative hypotheses is instructive. Subadditivity in assessments of qualitative hypotheses can be explained, in part at least, by the failure to consider one or more component hypotheses when the event in question is described in an implicit form. The subadditivity observed in judgments of quantitative hypotheses, however, cannot be explained as a retrieval failure. For example, Teigen (1974b, Experiment 2) found that the judged proportion of college students whose heights fell in a given interval increased when that interval was broken into several smaller intervals that were assessed separately. Results of Experiments Using Quantitative Hypotheses: Average Probability Assigned to Coextensional Implicit and Explicit Disjunctions and the Unpacking Factor Measuring the Degree of Subadditivity Note: the number of components in the explicit disjunction is denoted by n. The degree of subadditivity increases with the number of components in the explicit disjunction. This follows readily from support theory: Unpacking an implicit hypothesis into exclusive components increases its total judged probability, and additional unpacking of each component should further increase the total probability assigned to the initial hypothesis. Results of Experiments Testing Binary Complementarity: Average Total Probability Assigned to Complementary Pairs of Hypotheses, Between-Subjects Standard Deviations, and the Number of Subjects in the Experiment Note: Numbered studies with no citation refer to Tversky & Koehler, 1994. We considered only studies in which the hypothesis and its complement were evaluated independently, either by different subjects or by the same subjects but with a substantial number of intervening judgments. Binary complementarity indicates that people evaluate a given hypothesis relative to its complement. Moreover, it rules out alternative interpretations of subadditivity in terms of a suggestion effect or a confirmation bias.

C relatives C My brother is afraid of spiders hiv infection and aids pictures generic acivir pills 200 mg without prescription, roaches antiviral immune booster buy cheap acivir pills 200 mg on line, D interpretations and the like antiviral blog buy 200mg acivir pills with amex. Frost brings to life the which are as important as the poems hiv infection no fever purchase genuine acivir pills online, at times trees antiviral research impact factor 2015 buy discount acivir pills 200 mg line, mountains sore throat hiv infection symptoms acivir pills 200mg with amex, clifs, dirt burst with colors and at other times are sub roads, old fences, grassy felds, and abandoned dued with the pastel colors of fall and winter. Canto Familiar the Same Sky: A Collection of Poems from Around the World Gary Soto, the well-known writer for young adults, In her anthology, the Same celebrates the experience Sky: A Collection of Poems of growing up in a Mexican from Around the World, American community in Naomi Shihab Nye ofers Canto Familiar. Many of these up a large assortment of touching poems focus on poems from countries everyday tasks, such as wash in the Middle East, Asia, ing dishes or ironing clothes. Africa, India, and South Soto lovingly and humorously captures child and Central America. Both the joys debates with Stephen Douglas, and his strug and miseries of the immi gles as president during the years of the Civil gration process are captured in this historic War. A Great and Glorious Game the Harlem Renaissance Baseball was more than In the Harlem Renaissance, a game to A. Bartlett Veronica Chambers looks Giamatti; each game was back at a special time a drama that gave insight in American history. University through the period when he served Their work continues to infuence American cul as commissioner of baseball. Smartphone or Tablet To view documents from your smartphone or tablet, the free WinZip app is required. Non-Discrimination Aetna complies with applicable Federal civil rights laws and does not discriminate, exclude or treat people differently based on their race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability. Aetna provides free aids/services to people with disabilities and to people who need language assistance. If you need a qualified interpreter, written information in other formats, translation or other services, call 1-888-802-3862. If you believe we have failed to provide these services or otherwise discriminated based on a protected class noted above, you can also file a grievance with the Civil Rights Coordinator by contacting: Civil Rights Coordinator, P. Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Civil Rights Complaint Portal, available at ocrportal. Aetna is the brand name used for products and services provided by one or more of the Aetna group of subsidiary companies, including Aetna Life Insurance Company, Coventry Health Care plans and their affiliates (Aetna). It is one of three documents that together describe the benefits covered by your Aetna plan for in-network and out-of-network coverage. If you become covered, this booklet-certificate becomes your certificate of coverage under the group policy, and it replaces all certificates describing similar coverage that we sent to you before. The third document is the group policy between Aetna Life Insurance Company (Aetna) and your policyholder. Sometimes, these documents have amendments, inserts or riders which we will send you. Notice: the laws of the State of Georgia prohibit insurers from unfairly discriminating against any person based upon his or her status as a victim of family violence. Sometimes we use technical medical language that is familiar to medical providers. Coverage is not provided for any services received before coverage starts or after coverage ends. Family members can lose coverage for many reasons, such as growing up and leaving home. Eligible health services Doctor and hospitalservices are the base for many other services. They are health care services that meet these three requirements: x They appear in the Eligible health services under your plan section. Providers Our network of doctors, hospitals and other health care providers isthereto give you the careyou need. You can find network providersand see important information about them most easily on our online providerdirectory. You may go directly to network specialists and providers for eligible health services. You will find details on medical necessity and precertification requirements in the Medical necessity and precertification requirements section. For more information see the What the plan pays and what you pay section, and see the schedule of benefits. For more information see the When you disagree claim decisions and appeal procedures section. How your plan works while you are covered out-of-network You have coverage when you want to get your care from providers who are not part of the Aetna network. Your out-of-network coverage: x Means you may have to pay for services at the time they are provided. You may be required to pay the full charges and submit a claim for reimbursement to us. You are responsible for completing and submitting claim forms for reimbursement of eligible health services that you paid directly to a provider. You will find details on: x Precertification requirements in the Medical necessity and precertification requirements section x Out-of-network providersand any exceptions in the Who provides the care section x Cost sharing in the What the plan pays and what you pay section, and your schedule of benefits x Claim information in the When you disagree claim decisions and appeal procedures section How to contact us for help We are here to answer your questions. You can contact us by: x Logging on to your Aetna Navigator secure member website at. Aetna Navigator online tools will make it easier for you to make informed decisions about your health care, view claims, research care and treatment options, and access information on health and wellness. When you can join the plan As an employee you can enroll: x At the end of any waiting period your employer requires x Once each calendar yearduring the annual enrollment period x At other special times during the year (see the Special times you can join the plan section below) If you do not enroll when you first qualify for health benefits, you may have to wait until the next annual enrollment period to join. Who can be on your plan (who can be your dependent) If your plan includes coverage for dependents, you can enroll the following family members on your plan. See Adding new dependents and Special times you can join the plan for more information. Important note: You may continue coverage for a disabled child past the age limit shown above. See Continuation of coverage for other reasons in the Special coverage options after your coverage ends section for more information. Adding new dependents If your plan includes coverage for dependents, you can add the following new dependents to your plan: x A spouse If you marry, you can put your spouse on your plan. See Who can be on your plan (Who can be your dependent) section for more information. It will be on the date your Declaration of Domestic Partnership is filed or the first day of the month following the qualifying event date. It is usually the date of the adoption (or placement) or the first day of the month following adoption (or placement). A foster child is a child whose care, comfort, education and upbringing is left to persons other than the natural parents. It is usually the date you legally become a foster parent or the first day of the month following this event. It is the date of your marriage, declaration of domestic partnership or the first day of the month following the qualifying event date. It is usually the date of the court order or the first day of the month following the qualifying event date. Inform us of any changes It is important that you inform us of any changes that might affect your benefit status. We must receive your completed enrollment information from you within 31 days of the event or the date on which you no longer have the other coverage mentioned above. See the Eligible health services under your plan and Exceptions sections plus the schedule of benefits. Your plan pays for its share of the expense for eligible health services only if the general requirements are met. You will find the requirement to use a network provider and any exceptions in the Who provides the care section. The medical necessity requirements are in the Glossary section, where we define "medically necessary, medical necessity". Out-of-network: When you go to an out-of-network provider, you are responsible to obtain precertification from us for any services and supplies on the precertification list. The list of services and supplies that require precertification appears later in this section. Also, for any precertification benefit reduction that is applied, see the schedule of benefits Precertification benefit reduction section. For emergency services, precertification is not required, but you should notify us within the timeframeslisted below. This call must be made: You, your physician or the facility will: For non-emergency admissions Call and request precertification at least 14 days before the date you are scheduled to be admitted. For an emergency admission Call within 48 hours or as soon as reasonably possible after you have been admitted. An urgent admission is a hospitaladmission by a physician due to the onset of or change in an illness, the diagnosis of an illness, or an injury. For outpatient non-emergency medical services Call at least 14 days before the outpatient care is requiring precertification provided, or the treatment or procedure is scheduled. We will tell you and your physician in writing of the precertification decision, where required by state law. If your precertified services are approved, the approval is valid for 180 days as long as you remain enrolled in the plan. When you have an inpatient stay in a facility, we will tell you, your physician and the facility about your precertified length of stay. If your physician recommends that your stay be extended, additional days will need to be precertified. If precertification determines that the stay or services and supplies are not covered benefits, we will explain why and how our decision can be appealed. If you have questions about this section, see the How to contact us for help section. Your plan covers many kinds of health care services and supplies, such as physician care and hospital stays. But sometimes those services are not covered at all or are covered only up to a limit. For example: x Physician care generally is covered but physician care for cosmetic surgery is never covered.

For example hiv infection rates chicago buy generic acivir pills line, in nondeontic selection tasks the two systems lead to different responses hiv infection europe cheap acivir pills 200 mg mastercard. A deductive interpretation conjoined with an exhaustive search for falsifying instances yields the response P & not Q anti viral throat spray generic 200mg acivir pills free shipping. In deontic tasks hiv infection sore throat generic acivir pills 200mg on-line, both System 2 and System 1 processes (the latter in the form of preconscious relevance judgments antiviral in spanish best purchase for acivir pills, pragmatic schemas hiv infection rate in uae order acivir pills 200 mg without a prescription, or Darwinian algorithms; see Cheng & Holyoak, 1989; Cosmides, 1989; Cummins, 1996; Evans, 1996) operate to draw people to the correct response, thus diluting cognitive ability differences between correct and incorrect responders (see Stanovich & West, 1998a, for a data simulation). The experimental results reviewed here (see Stanovich, 1999, for further examples) reveal that the response dictated by the construal of the inventors of the Linda Problem (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983), Disease Problem (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981), and selection task (Wason, 1966) is the response favored by subjects of high analytic intelligence. The alternative responses dictated by the construals favored by the critics of the heuristics and biases literature were the choices of the subjects of lower analytic intelligence. These latter alternative construals may have been triggered by heuristics that make evolutionary sense (Cosmides & Tooby, 1994, 1996), but individuals higher in a more flexible type of analytic intelligence (and those more cognitively engaged, see Smith & Levin, 1996) are more prone to follow normative rules that maximize personal utility for the so-called vehicle, which houses the genes. Cognitive mechanisms that were fitness enhancing might well thwart our goals as personal agents in an industrial society (see Baron, 1998) because the assumption that our cognitive mechanisms are adapted in the evolutionary sense (Pinker, 1997) does not entail normative rationality. Thus, situations where evolutionary and normative rationality dissociate might well put the two processing Systems in conflict. These conflicts may be rare, but the few occasions on which they occur might be important ones. This is because knowledge-based, technological societies often put a premium on abstraction and decontextualization, and they sometimes require that the fundamental computational bias of human cognition be overridden by System 2 processes. An organism that could bring more relevant information to bear (not forgetting the frame problem) on the puzzles of life probably dealt with the world better than competitors and thus reproduced with greater frequency and contributed more of its genes to future generations. Evans and Over (1996) argue that an overemphasis on normative rationality has led us to overlook the adaptiveness of contextualization and the nonoptimality of always decoupling prior beliefs from problem situations. They note the mundane but telling fact that when scanning a room for a particular shape, our visual systems register color as well. They argue that we do not impute irrationality to our visual systems because they fail to screen out the information that is not focal. Our systems of recruiting prior knowledge and contextual information to solve problems with formal solutions are probably likewise adaptive in the evolutionary sense. The studies reviewed here indicate that those who do have the requisite flexibility are somewhat higher in cognitive ability and in actively open-minded thinking (see Stanovich & West, 1997). A conflict between the decontextualizing requirements of normative rationality and the fundamental computational bias may perhaps be one of the main reasons that normative and evolutionary rationality dissociate. The fundamental computational bias is meant to be a global term that captures the pervasive bias toward the contextualization of all informational encounters. All of these properties conjoined together represent a cognitive tendency toward radical contextualization. The bias is termed fundamental because it is thought to stem largely from System 1 and that system is assumed to be primary in that it permeates virtually all of our thinking. If the properties of this system are not to be the dominant factors in our thinking, then they must be overridden by System 2 processes so that the particulars of a given problem are abstracted into canonical representations that are stripped of context. In short, one of the functions of System 2 is to override some of the automatic contextualization provided by System 1. This override function might only be needed in a tiny minority of information processing situations (in most cases, the two systems interact in concert), but they may be unusually important ones. For example, numerous theorists have warned about a possible mismatch between the fundamental computational bias and the processing requirements of many tasks in a technological society containing many symbolic artifacts and often requiring skills of abstraction (Adler, 1984, 1991; Donaldson, 1978, 1993; Hilton, 1995). Einhorn and Hogarth (1981) highlighted the importance of decontextualized environments in their discussion of the optimistic (Panglossian/Apologist) and pessimistic (Meliorist) views of the cognitive biases revealed in laboratory experimentation. There is a caution in this comment for critics of the abstract content of most laboratory tasks and standardized tests. Evolutionary psychologists in the Apologist camp have concentrated on shaping the environment (changing the stimuli presented to subjects) so that the same evolutionarily adapted mechanisms that fail the standard of normative rationality under one framing of the problem give the normative response under an alternative. Their emphasis on environmental alteration provides a much-needed counterpoint to the Meliorist emphasis on cognitive change. The latter, with their emphasis on reforming human thinking, no doubt miss opportunities to shape the environment so that it fits the representations that our brains are best evolved to deal with. However, it is not always the case that the world willlet us deal with representations that are optimally suited to our evolutionarily designed cognitive mechanisms. Patterns of individual differences may alter our reflective equilibrium regarding the plausibility of the four alternative explanations for the normative/descriptive gap (performance errors, algorithmic limitations, wrong norm, and alternative construal). Different outcomes were obtained across the wide range of tasks we have examined in our research program. Of course, all the tasks had some unreliable variance and thus some responses that deviated from the response considered normative could easily be considered as performance errors. Finally, a few tasks yielded patterns of covariance that served to raise doubts about the appropriateness of the normative models applied to them or the task construals assumed by the problem inventors. Although many normative/descriptive gaps could be reduced by these mechanisms, not all of the discrepancies could be explained by factors that do not bring human rationality into question. The magnitude of the associations with cognitive ability left much room for the possibility that the remaining reliable variance indicates that there are systematic irrationalities in intentional-level psychology. A component of our research program mentioned only briefly has produced data consistent with this possibility. Specifically, once capacity limitations are controlled, the remaining variation from normative responding is not random (which would have indicated that the residual variance consisted largely of performance errors). In several studies, we have shown that there is significant covariance among the scores from a variety of tasks in the heuristics and biases literature after they are residualized on measures of cognitive ability (Stanovich, 1999). The residual variance (after partialling cognitive ability) is also systematically associated with questionnaire responses that can be conceptualized as intentional-level styles relating to epistemic regulation (Sa et al. These findings falsify models that attempt to explain the normative/descriptive gap entirely in terms of computational limitations and random performance errors. Instead, the findings support the notion that the normative/descriptive discrepancies that remain after computational limitations have been accounted for reflect a systematically suboptimal intentional-level psychology. Support Theory: A Nonextensional Representation of Subjective Probability* Amos Tversky and Derek J. Koehler Both laypeople and experts are often called upon to evaluate the probability of uncertain events such as the outcome of a trial, the result of a medical operation, the success of a business venture, or the winner of a football game. Such assessments play an important role in deciding, respectively, whether to go to court, undergo surgery, invest in the venture, or bet on the home team. Weather forecasters, for example, often report the probability of rain (Murphy, 1985), and economists are sometimes required to estimate the chances of recession (Zarnowitz, 1985). The theoretical and practical significance of subjective probability has inspired psychologists, philosophers, and statisticians to investigate this notion from both descriptive and prescriptive standpoints. Indeed, the question of whether degree of belief can, or should be, represented by the calculus of chance has been the focus of a long and lively debate. In contrast to the Bayesian school, which represents degree of belief by an additive probability measure, there are many skeptics who question the possibility and the wisdom of quantifying subjective uncertainty and are reluctant to apply the laws of chance to the analysis of belief. Besides the Bayesians and the skeptics, there is a growing literature on what might be called revisionist models of subjective probability. Recent developments have been reviewed by Dubois and Prade (1988), Gilboa and Schmeidler (1994), and Mongin (1994). Like the Bayesians, the revisionists endorse the quantification of belief, using either direct judgments or preferences between bets, but they find the calculus of chance too restrictive for this purpose. Consequently, they replace the additive measure, used in the classical theory, with a nonadditive set function satisfying weaker requirements. A fundamental assumption that underlies both the Bayesian and the revisionist models of belief is the extensionality principle: Events with the same extension are assigned the same probability. However, the extensionality assumption is descriptively invalid because alternative descriptions of the same event often produce systematically different judgments. The following three examples illustrate this phenomenon and motivate the development of a descriptive theory of belief that is free from the extensionality assumption. Although the car mechanics, who had an average of 15 years of experience, were surely aware of these possibilities, they discounted hypotheses that were not explicitly mentioned. Tversky and Kahneman (1983) constructed many problems in which both probability and frequency judgments were not consistent with set inclusion. For example, one group of subjects was asked to estimate the number of seven-letter words in four pages of a novel that end with ing. A second group was asked to estimate the number of seven-letter words that end with n. It appears that most people who evaluated the second category were not aware of the fact that it includes the first. Violations of extensionality are not confined to probability judgments; they are also observed in the evaluation of uncertain prospects. For example, Johnson, Hershey, Meszaros, and Kunreuther (1993) found that subjects who were offered (hypothetical) health insurance that covers hospitalization for any disease or accident were willing to pay a higher premium than subjects who were offered health insurance that covers hospitalization for any reason. Evidently, the explicit mention of disease and accident increases the perceived chances of hospitalization and, hence, the attractiveness of insurance. These observations, like many others described later in this article, are inconsistent with the extensionality principle. We distinguish two sources of nonextensionality: First, extensionality may fail because of memory limitation. As illustrated in Example 2, a judge cannot be expected to recall all of the instances of a category, even when he or she can recognize them without error. An explicit description could remind people of relevant cases that might otherwise slip their minds. Second, extensionality may fail because different descriptions of the same event may call attention to different aspects of the outcome and thereby affect their relative salience. Such effects can influence probability judgments even when they do not bring to mind new instances or new evidence. The common failures of extensionality, we suggest, represent an essential feature of human judgment, not a collection of isolated examples. They indicate that probability judgments are attached not to events but to descriptions of events. In this article, we present a theory in which the judged probability of an event depends on the explicitness of its description. This treatment, called support theory, focuses on direct judgments of probability, but it is also applicable to decision under uncertainty. Support Theory Let T be a finite set including at least two elements, interpreted as states of the world. We assume that exactly one state obtains but it is generally not known to the judge. This is a many-to-one mapping because different hypotheses, say A and B, may have the same extension. The following relations on H are induced by the corresponding relations on T :A iselementary if A T. If A and B are in H, and they are exclusive, then their explicit disjunction, denoted A B is also in H. A key feature of the present formulation is the distinction between explicit and implicit disjunctions. A is an implicit disjunction, or simply an implicit hypothesis, if it is neither elementary nor null, and it is not an explicit disjunction. Note that the explicit disjunction B C is defined for any exclusive B, C H, whereas a coextensional implicit disjunction may not exist because some events cannot be naturally described without listing their components. An evaluation frame (A, B) consists of a pair of exclusive hypotheses: the first elementA is the focal hypothesis that the judge evaluates and the second elementB is the alternative hypothesis. To simplify matters, we assume that when A and B are exclusive, the judge perceives them as such, but we do not assume that the judge can list all of the constituents of an implicit disjunction.

When these animals are born hiv infection rate south korea order acivir pills on line amex, they are studied to see whether their behavior differs from a control group of normal animals stages of hiv infection and treatment best buy acivir pills. Research has found that removing or changing genes in mice can affect their anxiety hiv and hcv co infection symptoms order acivir pills 200 mg without prescription, aggression hiv infection rate soars in uk buy acivir pills with american express, learning antiviral nanoparticles discount acivir pills amex, and socialization patterns hiv infection uk purchase acivir pills 200 mg free shipping. Research using molecular genetics has found genes associated with a variety of personality traits including novelty-seeking (Ekelund, Lichtermann, Jarvelin, & Peltonen, [10] [11] 1999), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Waldman & Gizer, 2006), and smoking [12] behavior (Thorgeirsson et al. Over the past two decades scientists have made substantial progress in understanding the important role of genetics in behavior. Behavioral genetics studies have found that, for most traits, genetics is more important than parental influence. And molecular genetics studies have begun to pinpoint the particular genes that are causing these differences. The results of these studies might lead you to believe that your destiny is determined by your genes, but this would be a mistaken assumption. Over time we will learn even more about the role of genetics, and our conclusions about its influence will likely change. Current research in the area of behavioral genetics is often criticized for making assumptions about how researchers categorize identical and fraternal twins, about whether twins are in fact treated in the same way by their parents, about whether twins are representative of children more generally, and about many other issues. Although these critiques may not change the overall conclusions, it must be kept in mind that these findings are relatively new and will certainly be [13] updated with time (Plomin, 2000). In fact, the major influence on personality is nonshared environmental influences, which include all the things that occur to us that make us unique individuals. These differences include variability in brain structure, nutrition, education, upbringing, and even interactions among the genes themselves. The genetic differences that exist at birth may be either amplified or diminished over time through environmental factors. The brains and bodies of identical twins are not exactly the same, and they become even more different as they grow up. As a result, even genetically identical twins have distinct personalities, resulting in large part from environmental effects. Because these nonshared environmental differences are nonsystematic and largely accidental or random, it will be difficult to ever determine exactly what will happen to a child as he or she grows up. Although we do inherit our genes, we do not inherit personality in any fixed sense. The effect of our genes on our behavior is entirely dependent upon the context of our life as it unfolds day to day. Based on your genes, no one can say what kind of human being you will turn out to be or what you will do in life. Because these differences are nonsystematic and largely accidental or random, we do not inherit our personality in any fixed sense. Do they seem to be very similar to each other, or does it seem that their differences outweigh their similarities. Behavioral genetics: An introduction to how genes and environments interact through development to shape differences in mood, personality, and intelligence. Sources of human psychological differences: the Minnesota study of twins reared apart. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Association between novelty seeking and the type 4 dopamine receptor gene in a large Finnish cohort sample. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Personalities are characterized in terms of traits, which are relatively enduring characteristics that influence our behavior across many situations. Psychologists have investigated hundreds of traits using the self-report approach. The utility of self-report measures of personality depends on their reliability and construct validity. The trait approach to personality was pioneered by early psychologists, including Allport, Cattell, and Eysenck, and their research helped produce the Five-Factor (Big Five) Model of Personality. The Big Five dimensions are cross-culturally valid and accurately predict behavior. The Big Five factors are also increasingly being used to help researchers understand the dimensions of psychological disorders. A difficulty of the trait approach to personality is that there is often only a low correlation between the traits that a person expresses in one situation and those that he or she expresses in other situations. However, psychologists have also found that personality predicts behavior better when the behaviors are averaged across different situations. People may believe in the existence of traits because they use their schemas to judge other people, leading them to believe that traits are more stable than they really are. The advantage of projective tests is that they are less direct, but empirical evidence supporting their reliability and construct validity is mixed. There are behaviorist, social-cognitive, psychodynamic, and humanist theories of personality. The psychodynamic approach to understanding personality, begun by Sigmund Freud, is based on the idea that all behaviors are predetermined by motivations that lie outside our awareness, in the unconscious. Freud proposed that the mind is divided into three components: id, ego, and superego, and that the interactions and conflicts among the components create personality. Freud also believed that psychological disorders, and particularly the experience of anxiety, occur when there is conflict or imbalance among the motivations of the id, ego, and superego and that people use defense mechanisms to cope with this anxiety. Freud argued that personality is developed through a series of psychosexual stages, each focusing on pleasure from a different part of the body, and that the appropriate resolution of each stage has implications for later personality development. Freudian theory led to a number of followers known as the neo-Freudians, including Adler, Jung, Horney, and Fromm. Humanistic theories of personality focus on the underlying motivations that they believed drive personality, focusing on the nature of the self-concept and the development of self-esteem. The idea of unconditional positive regard championed by Carl Rogers has led in part to the positive psychology movement, and it is a basis for almost all contemporary psychological therapy. Personality is not determined by any single gene, but rather by the actions of many genes working together. The role of nature and nurture in personality is studied by means of behavioral genetics studies including family studies, twin studies, and adoption studies. These studies partition variability in personality into the influence of genetics (known as heritability), shared environment, and nonshared environment. Although these studies find that many personality traits are highly heritable, genetics does not determine everything. In addition to the use of behavioral genetics, our understanding of the role of biology in personality recently has been dramatically increased through the use of molecular genetics, the study of which genes are associated with which personality traits in animals and humans. Robert scrutinized his face and body in the mirror for hours, finding a variety of imagined defects. Around this time, Robert had his first panic attack and began to worry that everybody could notice him sweating and blushing in public. His mother told the radio host, At the time we were really happy because we thought that finally we actually knew what we were trying to fight and to be quite honest, I must admit I thought well it sounds pretty trivial. However, a lighthearted comment from a friend about a noticeable vein in his forehead prompted a relapse. He then used injections on himself to try opening the vein again, but he could never completely reverse the first surgery. Describe the stigma of psychological disorders and their impact on those who suffer from them. About 1 in every 4 Americans (or over 78 million people) are affected by a psychological disorder during any one year (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & [1] Walters, 2005), and at least a half billion people are affected worldwide. People with psychological disorders are also stigmatized by the people around them, resulting in shame and embarrassment, as well as prejudice and discrimination against them. Thus the understanding and treatment of psychological disorder has broad implications for the everyday life of many people. We will review the major psychological disorders and consider their causes and their impact on the people who suffer from them. Then in Chapter 13 "Treating Psychological Disorders", we will turn to consider the treatment of these disorders through psychotherapy and drug therapy. Like medical problems, psychological disorders have both biological (nature) as well as environmental (nurture) influences. These causal influences are reflected in the bio-psycho-social model of [3] illness (Engel, 1977). The bio-psycho-social model of illness is a way of understanding disorder that assumes that disorder is caused by biological, psychological, and social factors (Figure 12. Particularly important are genetic characteristics that make some people more vulnerable to a disorder than others and the influence of neurotransmitters. The psychological component of the bio-psycho social model refers to the influences that come from the individual, such as patterns of negative thinking and stress responses. Thesocial component of the bio-psycho-social model refers to the influences on disorder due to social and cultural factors such as socioeconomic status, homelessness, abuse, and discrimination. To consider one example, the psychological disorder of schizophrenia has a biological cause because it is known that there are patterns of genes that make a person vulnerable to the disorder [4] (Gejman, Sanders, & Duan, 2010). But whether or not the person with a biological vulnerability experiences the disorder depends in large part on psychological factors such as how the individual responds to the stress he experiences, as well as social factors such as whether or not he is exposed to stressful environments in adolescence and whether or not he has support from people who care about him (Sawa & Snyder, 2002; Walker, Kestler, Bollini, & Hochman, [5] 2004). Although they share many characteristics with them, psychological disorders are nevertheless different from medical conditions in important ways. Current research is beginning to provide more evidence about the role of brain structures in psychological disorder, but for now the brains of people with severe mental disturbances often look identical to those of people without such disturbances. Because there are no clear biological diagnoses, psychological disorders are instead diagnosed on the basis of clinical observations of the behaviors that the individual engages in. Whether a given behavior is considered a psychological disorder is determined not only by whether a behavior is unusual. The focus on distress and dysfunction means that behaviors that are simply unusual (such as some political, religious, or sexual practices) are not classified as disorders. For each, indicate whether you think the behavior is or is not a psychological disorder. Charlie believes that the noises made by cars and planes going by outside his house have secret meanings. He is convinced that he was involved in the start of a nuclear war and that the only way for him to survive is to find the answer to a difficult riddle. He worries about driving on the highway and about severe weather that may come through his neighborhood. But mostly he fears mice, checking under his bed frequently to see if any are present.

Discount acivir pills 200 mg mastercard. How to Recognize and Understand HIV Symptoms - Health is Wealth.

References

- Caplan LR. Caudate hemorrhage. In: Kase CS, Caplan LR, editors. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1994.

- Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, et al: A randomized trial of intravesical doxorubicin and immunotherapy with bacille Calmette-Guerin for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, N Engl J Med 325:1205n1209, 1991.

- Vijayan A, Faubel S, Askenazi D, et al. Clinical Use of the Urine Biomarker [TIMP-2] x [IGFBP7] for acute Kidney Injury Risk Assessment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(1):19-28.

- Yazici H, Yurdakul S, Hamuryudan V. Behcet's syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1999;11(1):53-7.

- Gagnon JF, Bedard MA, Fantini ML, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia in Parkinsonis disease. Neurology 2002;59(4):585-9.

- Heilbrun MP, Olesen J, Lassen NA. Regional cerebral blood flow studies in subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1972;37: 36-44.

- Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, et al. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide versus autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone versus lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;16(16):1617-1629.