James L. Whiteside, MD

- Assistant Professor, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Dartmouth Medical

- School, Lebanon, New Hampshire

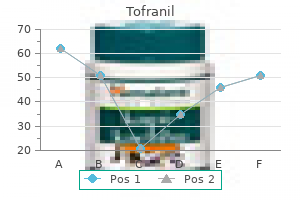

The American journal of fstulas with or without cerebral sinus roentgenology anxiety symptoms checklist 90 buy 50mg tofranil mastercard, radium therapy anxiety jaw clenching buy generic tofranil 50mg online, and thrombosis: analysis of 69 patients anxiety hypnosis cheap tofranil line. Dural arteriove Dural arteriovenous malformation sec nous fstula of the anterior fossa treated ondary to meningioma removal anxiety 5-htp cheap tofranil line. Cardiovascular and interventional out embolization for intracranial dural radiology anxiety symptoms 4 days tofranil 25mg with mastercard. They are not intended to define a standard of care and should not be construed as one anxiety symptoms in young males generic 25 mg tofranil with visa. In addition, they should not be interpreted as prescribing an exclusive course of management. Variations in practice will inevitably and appropriately occur when providers take into account the needs of individual patients, available resources, and limitations unique to an institution or type of practice. Every healthcare professional making use of these guidelines is responsible for evaluating the appropriateness of applying them in the setting of any particular clinical situation. Approximately 50, 000 Americans die each year following traumatic brain injury, representing one third of all injury-related deaths. Only a small sub-set of these patients (10%) experience post-injury symptoms of a long lasting nature. Due to numerous deployments and the nature of enemy tactics, troops are at risk for sustaining more than one mild brain injury or concussion in a short timeframe. Based on these efforts, the task force developed a consensus document that included definitions, classification and taxonomy. These protocols have been considered the seed for the development of this Evidence Based Practice Guideline. The literature identified by the search was critically analyzed and graded using a standardized format applying the evidence grading system used by the U. The algorithms serve as a guide that providers can use to determine best interventions and timing of services for their patients to optimize quality of care and clinical outcomes. This should not prevent providers from using their own clinical expertise in the care of an individual patient. Guideline recommendations are intended to support clinical decision-making but should never replace sound clinical judgment. Although this guideline represents the state of the art practice at the time of its publication, medical practice is evolving and this evolution will require continuous updating of published information. New technologies and increased ongoing research will improve patient care in the future. Future studies examining the results of clinical practice guidelines such as these may lead to the development of new practice-based evidence and treatment modalities. A recently developed program that has been created for post-deployment personnel and veterans experiencing head injury deserves mention here. The providers in these settings have received specialty training in this condition and treatment approaches. The role of neuropsychological and physiological testing, in an attempt to further characterize the injury, needs additional application and study. Therefore, in annotations for which there are evidence based studies to support the recommendations a section titled Evidence Statements follows the recommendations and provides a brief discussion of findings. In annotations for which there is not a body of evidence based literature there is a Discussion Section which discusses approaches defined through assessing expert opinion on the given topic. At least fair evidence was found that the intervention improves health outcomes and concludes that benefits outweigh harm. D Recommendation is made against routinely providing the intervention to patients. Evidence that the intervention is effective is lacking, or poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. The symptoms occur frequently in day to day life among healthy individuals and are also found often in persons with other conditions such as chronic pain or depression. Criteria for characterizing post-traumatic headaches as tension-like (including cervicogenic) or migraine-like based upon headache features. Progressively declining or disoriented to placeor disoriented to place 33 neurological examneurological exam 9. Pupillary asymmetry confused and irritableconfused and irritable NoNo evaluation andevaluation and 4. Assign case manager to:Assign case manager to: Follow-up and coordinate (remind) Follow-up and coordinate (remind) 99 NoNo future appointmentsfuture appointments Reinforce early interventions and Reinforce early interventions and Initiating symptom-based treatmentInitiating symptom-based treatment educationeducation [ B-8 ][ B-8 ] Address psychosocial issues Address psychosocial issues Consider case managementConsider case management (financial, family, housing or(financial, family, housing or (See sidebar 7)(See sidebar 7) school/work)school/work) 1010 Connect to available resources Connect to available resources Follow-up and reassess in 4-6Follow-up and reassess in 4-6 weeksweeks [B-9][B-9] 1212 1111 Are all symptomsAre all symptoms YesYes Follow-up as neededFollow-up as needed sufficientlysufficiently Encourage & reinforceEncourage & reinforce resolved Co-occurring conditions (chronic pain, Reassess symptoms severity andReassess symptoms severity and mood disorders, stress disorder, mood disorders, stress disorder, functional statusfunctional status personality disorder)personality disorder) Complete psychosocial evaluationComplete psychosocial evaluation 4. Unemployment or change in job status 33 Are symptoms andAre symptoms and functional statusfunctional status YesYes improved NoNo 77 44 Assess for possible alternativeAssess for possible alternative Initiate/continueInitiate/continue causes for persistent symptoms; causes for persistent symptoms; symptomatic treatmentsymptomatic treatment Consider behavioral componentConsider behavioral component Provide patient and familyProvide patient and family. External forces may include any of the following events: the head being struck by an object, the head striking an object, the brain undergoing an acceleration/deceleration movement without direct external trauma to the head, a foreign body penetrating the brain, forces generated from events such as a blast or explosion, or other forces yet to be defined. If a patient meets criteria in more than one category of severity, the higher severity level is assigned. Typical symptoms would be: looking and feeling dazed and uncertain of what is happening, confusion, difficulty thinking clearly or responding appropriately to mental status questions, and being unable to describe events immediately before or after the trauma event. The patient who is told s/he has "brain damage" based on vague symptoms complaints and no clear indication of significant head trauma may develop a long-term perception of disability that is difficult to undo (Wood, 2004). This led the Working Group to rely on expert opinion in determining recommendations for intervention. The most typical signs and symptoms after concussion fall into one or more of the following three categories: a. Physical: headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, fatigue, blurred vision, sleep disturbance, sensitivity to light/noise, balance problems, transient neurological abnormalities b. Signs and symptoms may occur alone or in varying combinations and may result in functional impairment. These symptoms occur frequently in day-to day life among healthy individuals and are often found in persons with other conditions such as chronic pain, depression or other traumatic injuries. These symptoms are also common to any number of pre existing/pre-morbid conditions the patient may have had. Each patient tends to exhibit a different mix of symptoms and the symptoms themselves are highly subjective in nature. Symptoms do not appear to cluster together in a uniform, or even in a consistent expected trend. The presence of somatic symptoms is not linked predictably to the presence of neuropsychiatric. Few persons with multiple post concussion symptoms experience persistence of the entire set of their symptoms over time. Annotation A-5 Is Person Currently Deployed on Combat or Ongoing Military Operation Management of service members presenting for care immediately after a head injury (within 7 days) during military combat or ongoing operation should follow guidelines for acute management published by DoD. Management of non-deployed service members, veterans, or civilian patients presenting for care immediately after a head injury (within 7 days) should follow guidelines for acute management. Algorithm A (Initial Presentation) describes a new entry into the healthcare system and is not dependent on the time since injury. It does not follow the traditional acute, sub-acute, and post-acute phases of brain injury. Algorithm C (Follow-up Persistent Symptoms) will apply to any service person/veteran for whom treatment of concussion symptoms previously had been started. Despite the long elapsed time since injury, the provider uses Algorithm A and B for the initial work-up to make the diagnosis and initiate treatment. If the symptoms do not remit within 4 to 6 weeks of the initial treatment, the provider follows Algorithm C to manage the persistent symptoms. Patients who continue to have persistent symptoms despite treatment for persistent symptoms (Algorithm C) beyond 2 years post-injury do not require repeated assessment for these chronic symptoms and should be conservatively managed using a simple symptom-based approach. Patients with symptoms that develop more than 30 days after a concussion should have a focused diagnostic work-up specific to those symptoms only. These symptoms are highly unlikely to be the result of the concussion and therefore the work-up and management should not focus on the initial concussion. Symptomatic individuals will frequently present days, weeks, or even months after the trauma. These delays are associated with the injured person discounting symptoms, incorrectly interpreting symptoms, guilt over the circumstances involved in the injury, and denial that anything serious occurred (Mooney et al. As a result, the important focus should be on treating the symptoms rather than on determining the etiology of the symptoms. This difficulty is due to the subjective nature of these symptoms, the very high base rates of many of these symptoms in normal populations (Iverson, 2003; Wang, 2006), and the many other etiologies that can be associated with these symptoms. Since post-concussive symptoms may occur as non-specific responses to trauma, studies compare patients with concussions to patients with other types of trauma. Therefore, not only are these symptoms non-specific responses to trauma, it is also unclear if timing of the onset of symptoms can be helpful in determining if they are due to the concussion (Boake et. The association of post-concussion syndrome with concussion has not met generally accepted epidemiological criteria for causation. A study that directly compared the two definitions showed poor correlation between them and there was no way to determine which one is more accurate (Boake et al. Various studies of persisting symptoms have employed various symptom checklists rather than uniform criteria-based diagnoses. As a result, large differences are reported in the frequency of patients meeting the diagnostic criteria sets. Some have argued that the rate of 15percent, initially reported by many, is incorrect and argued that the more accurate rate may be closer to 3-5 percent (Iverson, 2007; McCrea, 2007). Annotation A-8 Provide Education and Access Information; Follow-Up as Indicated 1. Patients should be provided with written contact information and be advised to contact their healthcare provider for follow-up if their condition deteriorates or they develop symptoms. This guideline recommends that these individuals will be first treated following the algorithm and annotations in Algorithms A and B. Patients managed in Algorithm B are service persons or veterans identified by post deployment screening, or who present to care with symptoms or complaints related to head injury. Patients presenting for care immediately after head injury (within 7 days) should follow guidelines for acute management and should not use this algorithm. Therefore, the purpose of the assessment may vary slightly based on the timing of the presentation following injury. For patients presenting immediately after the injury event, assessment will include the necessity to rule out neurosurgical emergencies. In patients who present with delayed injury-to assessment intervals, the assessment will include confirmation linking the symptoms to the concussive event. Obtaining detailed information of the injury event including mechanism of injury, duration and severity of alteration of consciousness, immediate symptoms, symptom course and prior treatment c. Evaluating signs and symptoms indicating potential for neurosurgical emergencies that require immediate referrals. A concussion is not a contraindication for referral to a substance abuse treatment program. A focused vision examination including gross acuity, eye movement, binocular function and visual fields/attention testing c. A focused musculoskeletal examination of the head and neck, including range of motion of the neck and jaw, and focal tenderness and referred pain. The biomarker that has been most widely studied, S-100B, is only detectable in the first few hours after injury. In addition, S-100B has not been shown to be related to the development of headaches at three months (Bazarian et al. Various neuroimaging modalities can be employed in helping to identify structural neuropathology. However, many of these modalities are still at the preliminary/research stage of development. A patient who presents with any signs or symptoms that may indicate an acute neurologic condition that requires urgent intervention should be referred for evaluation that may include neuroimaging studies. The presence of this potentially fatal complication may become apparent only after there is clinical deterioration. Other imaging techniques may be used to investigate persistent symptoms and deterioration.

Some institutions administer carbapenems (namely imipenem/cilastin and meropenem) to patients with penicillin allergy anxiety hypnosis order tofranil 25mg free shipping, as they felt that the potential for cross-reactivity 19 between carbapenems and penicillin is less than traditionally believed ms symptoms anxiety zone generic 75mg tofranil mastercard. The first 9 guidelines (published between 1955 and 1997) were based on low-level evidence; only more recently have the guidelines been stratified based on lifetime risk of infective endocarditis anxiety symptoms for hiv buy cheap tofranil 50 mg on-line. Consensus: Curently teicoplanin and vancomycin are reasonable alternatives when routine antibiotic prophylaxis cannot be administered papa roach anxiety buy tofranil 25 mg with amex. As vancomycin is more difficult to administer and has a shorter half-life and poorer tolerability profile than teicoplanin anxiety attack symptoms order 25mg tofranil free shipping, the latter 34 may be a better choice in these settings anxiety attack help tofranil 50 mg. Consensus: In a patient with a known anaphylactic reaction to penicillin, vancomycin or clindamycin should be administered as prophylaxis. Delegate Vote: Agree: 88%, Disagree: 10%, Abstain: 2% (Strong Consensus) Question 5B: What antibiotic should be administered in a patient with a known non anaphylactic penicillin allergy Penicillin skin testing may be helpful in certain situations to clarify whether the patient has a true penicillin allergy. Delegate Vote: Agree: 87%, Disagree: 9%, Abstain: 4% (Strong Consensus) Justification: When patients present with a penicillin allergy, further information should be obtained to determine whether an Immunoglobulin E(IgE)-mediated response (anaphylaxis) occurred. Vancomycin and clindamycin are recommended as alternative agents for patients who have a true type I lactam allergy, manifested by immediate urticaria, laryngeal edema, or 3 bronchospasm. Therefore a second agent should be considered (levofloxacine, moxi-floxacine) in addition to 8 vancomycin. The high cross-reactivity found in earlier studies may be due in part to 39, 40 contamination of the study drugs with penicillin during the manufacturing process. Twenty-seven articles on the topic of the cross-reactivity of penicillin and cephalosporin were reviewed, of which 2 were meta-analyses, 12 were prospective cohorts, 3 were retrospective cohorts, 2 were surveys, and 9 were laboratory studies. Moreover, laboratory and cohort studies indicate that the R1 side chain, not the lactam ring, is responsible for this cross-reactivity. For penicillin-allergic patients, the use of third or fourth generation cephalosporin or cephalosporins (such as cefuroxime and ceftriaxone) with 45 dissimilar side chains than the offending penicillin carries a negligible risk of cross allergy. The relative risk of an anaphylactic reaction to cephalosporin ranges from 1:1, 000 to 1:1, 000, 000 47 and this risk is increased by a factor of 4 in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Based on an analysis of 9 articles that compare allergic reactions to a cephalosporin in penicillin-allergic and non-penicillin-allergic subjects, Pichichero et al. The rate of presumed IgE-mediated adverse drug reactions to the cephalosporin among the cases was 2 50 (2%) of 85 compared to 1 (0. Delegate Vote: Agree: 93%, Disagree: 6%, Abstain: 1% (Strong Consensus) Justification: Current data suggest that the role of vancomycin in orthopaedic surgery prophylaxis should be limited. Several systematic analyses concluded that no clear benefit in clinical or cost effectiveness has been demonstrated for the routine use of vancomycin compared with cephalosporin for prophylaxis. The choice of drug prophylaxis should take into account the antibiotic resistance patterns in hospital systems. Thirty-three of the 194 infections were diagnosed within a month after the surgery. The cost-effectiveness review included 5 economic evaluations of glycopeptide prophylaxis. Only one study incorporated health-related quality of 66 life and undertook a cost-utility analysis. A trend toward more methicillin-resistant gram-positive infections was observed in the cefazolin group (4. In a prospective, multicenter study of 362 knee and 2, 651 hip arthroplasty cases, the authors reported a deep joint infection rate of 2. Of 1, 934 surgical cases (1, 291 orthopaedic surgeries) performed at a Veterans Administration hospital, a preoperative urine culture was obtained in 25% (489) of cases. Of these, bacteriuria 71 was detected in 54 (11%) patients, of which only 16 received antimicrobial drugs. Another retrospective analysis found 57 (55 asymptomatic, 2 symptomatic) of 299 arthroplasty patients had bacteriuria on admission. Question 10: Should the preoperative antibiotic choice be different in patients who have previously been treated for another joint infection In these patients, we recommend the use of antibiotic-impregnated cement, if a cemented component is utilized. Intraoperatively, frozen section for evidence of acute inflammation was used to guide decisions on whether the procedure was done as a single or staged procedure. There is no evidence to support the support the continued use of postoperative antibiotics when urinary catheter or surgical drains are in place. Prophylactic antibiotics should be discontinued within 24 hrs of the end of surgery. Of the 99 patients who completed the study, 14 patients (5 men, 9 women) developed postoperative bacteriuria. The indwelling catheter group had a bacteriuria rate of 24% (11/46) compared with 6% (3/53) in the 109 intermittent catheterization group (p=0. In a survey of the members of the American Society of Breast Surgeons regarding the use of perioperative antibiotics for breast operations requiring drains, respondents continued antibiotic prophylaxis for 2-7 days or until all drains were removed (38% and 39% respectively) in cases without reconstruction, while in reconstruction cases 33% of respondents continued antibiotic 112 prophylaxis for 2-7 days or until all drains were removed. A similar study surveying the American and Canadian societies of Plastic Surgeons regarding drain use and perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in cases of breast reconstruction found that 72% of plastic surgeons prescribed postoperative outpatient antibiotics in reconstruction patients with drains, with 46% 113 continuing antibiotics until drains were removed. Consensus: Postoperative antibiotics should not be administered for greater than 24 hours after surgery. Delegate Vote: Agree: 87%, Disagree: 10%, Abstain: 3% (Strong Consensus) Justification: Many studies across surgical specialties have been performed to compare durations of antibiotic prophylaxis and the overwhelming majority have not shown any benefit in 114-116 antibiotic use for more than 24 hours in clean elective cases. No deep infections developed in either the one-dose or 48-hour antibiotic protocol group. The authors recognized that as a result of the small sample sizes, the study lacked the power to compare the one dose and the 118 more than one dose categories. Delegate Vote: Agree: 96%, Disagree: 1%, Abstain: 3% (Strong Consensus) Justification: Guidelines based on individual institutional microbiological epidemiology should 124 be developed. Of the 248 isolated microorganisms, staphylococcus species was the most common genus encountered (53%), followed by gram-negative isolates (24%). Vancomycin and teicoplanin were the most effective antibiotics, with overall sensitivity rates of 100% and 96% respectively. The authors also noted an increase in antimicrobial resistance (24% resistance to gentamicin), which lead the authors to suggest that other antibiotics such as erythromycin or fusidic acid be added to bone cement during these 127 procedures. Timing of Infection: A retrospective analysis of 146 patients who had a total of 194 positive cultures obtained at time of revision total hip or knee arthroplasty was performed. The microorganisms were sensitive to cefazolin in 61% of cases, gentamicin in 88% of cases, and vancomycin in 96% of cases. The most antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains were from patients for whom prior antibiotic treatment had failed. Acute postoperative infections had a greater resistance profile than did chronic or hematogenous infections. Bacteria isolated from a hematogenous infection had a high sensitivity to both cefazolin and gentamicin. All chronic and acute postoperative infections with gram-positive bacteria and all cases in which a gram stain fails to identify bacteria should be managed with vancomycin. Infections with mixed gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria should be managed with a combination of vancomycin and third or fourth generation cephalosporin. In a retrospective review of 97 patients (106 infections in 98 hips), Tsukayama et al. The authors noted that most of the gram-negative isolates came from the early postoperative and late chronic infections, while isolates from the acute hematogenous infections were exclusively 130 gram-positive cocci. Most gram-negative isolates were resistant to cefuroxime and all were sensitive to meropenem. Consensus: the appropriate preoperative antibiotic for the second stage should include coverage of the prior organism(s). Delegate Vote: Agree: 66%, Disagree: 31%, Abstain: 3% (Strong Consensus) Justification: Patients undergoing reimplantation surgery following a two-stage exchange 132, 133 procedure are at risk of developing recurrent infection. The recurrent infection may be either due to incomplete eradication of the prior bacteria during the antibiotic spacer exchange or to a new infection. While there is no evidence to support 82 the practice, it makes theoretical sense to add antibiotics that are effective in treating the index infection. Of these, the infection was considered recurrent in 0%-18% of cases, while new infection rates varied from 0 to 31%. While the length of follow-up did not appear to influence the rate of recurrent infections, 134 the studies with <4 years of clinical follow-up had fewer new infections. Of this cohort, the isolated organism was different from the previous infecting organism in only one of 132 18 patients. At 60 minutes after the incision, blood loss correlated with cefazolin tissue concentrations (r=-0. A strong negative correlation was found between the intravenously 145 administered fluids and gentamicin concentrations in serum and tissues (p<=0. There was a modest inverse correlation between blood loss and the intraoperative serum half-life of vancomycin. Thus blood loss during orthopaedic procedures has a minimal effect on the intraoperative kinetics of vancomycin and administering 146 vancomycin every 8 to 12 hours seems appropriate for most patients. Consensus: Preoperative antibiotics have different pharmacokinetics based on patient weight and should be weight-adjusted. Delegate Vote: Agree: 95%, Disagree: 4%, Abstain: 1% (Strong Consensus) 87 Justification: Because of the relative unpredictability of pharmacokinetics in obese individuals, doses are best estimated on the basis of specific studies for individual drugs carried out in this population. Only a few antibiotics (aminoglycosides, vancomycin, daptomycin, and linezolid) have been studied in the obese population. Dose amount should be proportional to patient weight; for patients 2 >80 kg, the doses of cefazolin should be doubled. However, there is literature to support the use of higher doses of vancomycin, with emphasis that doses >4g/day have been associated with increased risk of nephrotoxicity. As a general rule, obese and morbidly obese patients require higher doses of cephalosporin to achieve similar outcomes; however, there are fewer absolute dosing recommendations. Blood samples were collected up to 4 hours post dosing to determine the total and unbound plasma cefazolin concentrations. Consensus: Until the emergence of further evidence, we recommend the use of routine antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing major reconstruction. Despite this there is insufficient evidence to suggest that a different perioperative antibiotic regimen is warranted. The authors convincingly demonstrated that megaprostheses coated with silver showed a significantly lower infection rate 173 (7% vs 47%, p<0. However, the authors note 94 that the operating time required for the proximal tibia replacement was significantly shorter in the silver-coated prosthesis group (p=0. Tsuchiya et al reported that iodine-supported implants were used to prevent infection in 257 patients with compromised status. The results indicate that iodine-supported titanium has 170 favorable antibacterial activity, biocompatibility, and no cytotoxicity. Reviewing 197 patients (77 patients with a cobalt chrome alloy system and 120 patients with a titanium alloy system) who underwent lower extremity reconstruction with a megaprosthesis, the authors reported a 31. When they performed a secondary analysis matching two identical subgroups, the cobalt chrome group was still associated with a significantly higher infection rate, with 5 174 infections of 26 megaprostheses vs one infection of 36 titanium megaprostheses (p<0. Additionally, bulk allografts are used most often in the setting of revision arthroplasty when there is frequently additional local soft tissue and vascular compromise, which compounds the risk for infection. Therefore, it would seem reasonable to want to modify the perioperative antibiotic protocol to protect these reconstructions. Unfortunately, there is insufficient literature to support altering antibiotic regimens, as most studies on the use of bulk allograft do not indicate or detail the antibiotic regimens utilized. Even if this data were available, it would not be accurate to properly compare the infection rates of different clinical series based on their perioperative antibiotic protocols because of the heterogeneity of patient populations. While there is no current literature applying this technology to the use of bone defects in infected revision arthroplasty, it may be a promising technique. In addition, no adverse effects were seen 180 and the incorporation of bone graft was comparable to unimpregnated grafts. In this study the authors reported using prophylactic antibiotics (cephalosporins) preoperatively and 3 doses postoperatively and added antibiotic powder (vancomycin and tobramycin) to the cement in 2 patients thought to be at high risk for 193 infection. The authors again used antibiotic (vancomycin)-impregnated bone cement in all cemented 196 cases. In this study, 203 perioperative prophylactic antibiotics were administered for 2 to 5 days. Analyzing 72 patients (77 joint replacements), the authors found that fibrotic hepatitis C patients had higher deep infection rates (21 vs 0%, p =0. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis should be the same for primary and uninfected revision arthroplasty. Delegate Vote: Agree: 89%, Disagree: 10%, Abstain: 1% (Strong Consensus) Question 21B: Should preoperative antibiotics be different for hips and knees Consensus: Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis should be the same for hips and knees. Following introduction of vancomycin to the routine preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis, the infection rate decreased from 7. Delegate Vote: Agree: 76%, Disagree: 8%, Abstain: 16% (Strong Consensus) Justification: There is an increasing awareness of the threat posed by K. Recommendations for the Use of Intravenous Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project.

McVary anxiety fever cheap tofranil 75 mg without a prescription, Eli Lilly(C) anxiety symptoms paranoia tofranil 50 mg with mastercard, Allergan(C) anxiety 24 hour hotline generic tofranil 50mg on-line, Watson Pharmaceuticals(C) anxiety 7 year old daughter tofranil 25mg, Neotract(C) anxiety symptoms after eating cheap 75 mg tofranil with amex, Ferring(C); Reginald C anxiety quotes images purchase tofranil 50 mg on-line. Roehrborn, American Medical Systems(C), GlaxoSmithKline(C), Lilly(C), Neotract(C), Neri(C), NxThera(C), Pfizer(C), Warner Chilcot(C), Watson(C); Steven A. As medical knowledge expands and technology advances, the guideline statements will change. Today these evidence-based guideline statements do not represent absolute mandates, but do represent provisional proposals for treatment under the specific conditions described in each document. For all these reasons, the guideline statements do not pre-empt physician judgment in individual cases. Also, treating physicians must take into account variations in resources, and in patient tolerances, needs and preferences. Lee C, Kozlowski J, Grayhack J: Intrinsic and extrinsic factors controlling benign prostatic growth. Auffenberg G, Helfan B, McVary K: Established medical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Reynard J: Does anticholinergic medication have a role for men with lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia either alone or in combination with other agents Wei J, Calhoun E, Jacobsen S: Urologic diseases in America project: benign prostatic hyperplasia. Di Silverio F, Gentile V, Pastore A et al: Benign prostatic hyperplasia: what about a campaign for prevention In: 6th International Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Prostate Diseases. Abrams P, Chapple C, Khoury S et al: Evaluation and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older men. Abrams P, Chapple C, Khoury S et al: Evaluation and Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Older Men. Caine M, Raz S, Zeigler M: Adrenergic and cholinergic receptors in the human prostate, prostatic capsule and bladder neck. Oshika T, Ohashi Y, Inamura M et al: Incidence of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome in patients on either systemic or topical alpha(1)-adrenoceptor antagonist. Amin K, Fong K, Horgan S: Incidence of intra-operative floppy iris syndrome in a U. Blouin M, Blouin J, Perreault S et al: Intraoperative floppy-iris syndrome associated with 1 adrenoreceptors Comparison of tamsulosin and alfuzosin. Cheung C, Awan M, Sandramouli S: Prevalence and clinical findings of tamsulosin-associated intraoperative floppy-iris syndrome. Takmaz T, Can I: Clinical features, complications, and incidence of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome in patients taking tamsulosin. Clark R, Hermann D, Cunningham G et al: Marked suppression of dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia by dutasteride, a dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor. Ju X, Wu H, Zhang W et al: the clinical efficacy of epristeride in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. McConnell J, Wilson J, Goerge F et al: Finasteride, and inhibitor of 5Reductase, suppresses prostatic dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Wurzel R, Ray P, Major-Walker K et al: the effect of dutasteride on intraprostatic dihydrotestosterone concentrations in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Kramer B, Hagerty K, Justman S et al: Use of 5-Reductase Inhibitors for Prostate Cancer Chemoprevention: American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Urological Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guideline Summary. Kramer B, Hagerty K, Justman S et al: Use of 5alpha-reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer chemoprevention: American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Urological Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guideline. Roehrborn C, Prajsner A, Kirby R et al: A double-blind placebo-controlled study evaluating the onset of action of doxazosin gastrointestinal therapeutic system in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Roehrborn C, Lukkarinen O, Mark S et al: Long-term sustained improvement in symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia with the dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor dutasteride: results of 4 year studies. Barkin J, Guimaraes M, Jacobi G et al: Alpha-blocker therapy can be withdrawn in the majority of men following initial combination therapy with the dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor dutasteride. Foley S, Soloman L, Wedderburn A et al: A prospective study of the natural history of hematuria associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia and the effect of finasteride. Haggstrom S, Torring N, Moller K et al: Effects of finasteride on vascular endothelial growth factor. Pareek G, Shevchuk M, Armenakas N et al: the effect of finasteride on the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and microvessel density: a possible mechanism for decreased prostatic bleeding in treated patients. Miller M, Puchner P: Effects of finasteride on hematuria associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: long-term follow-up. Delakas D, Lianos E, Karyotis I et al: Finasteride: a long-term follow-up in the treatment of recurrent hematuria associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Hahn R, Fagerstrom T, Tammela T et al: Blood loss and postoperative complications associated with transurethral resection of the prostate after pretreatment with dutasteride. Boccon-Gibod L, Valton M, Ibrahim H et al: Effect of dutasteride on reduction of intraoperative bleeding related to transurethral resection of the prostate. Sandfeldt L, Bailey D, Hahn R: Blood loss during transurethral resection of the prostate after 3 months of treatment with finasteride. Donohue J, Sharma H, Abraham R et al: Transurethral prostate resection and bleeding: a randomized, placebo controlled trial of role of finasteride for decreasing operative blood loss. Crea G, Sanfilippo G, Anastasi G et al: Pre-surgical finasteride therapy in patients treated endoscopically for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Athanasopoulos A, Gyftopoulos K, Giannitsas K et al: Combination treatment with an alpha blocker plus an anticholinergic for bladder outlet obstruction: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Wilt T, Ishani A, Stark G et al: Saw palmetto extracts for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review. Cimentepe E, Unsal A, Saglam R: Randomized clinical trial comparing transurethral needle ablation with transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: results at 18 months. Hindley R, Mostafid A, Brierly R et al: the 2-year symptomatic and urodynamic results of a prospective randomized trial of interstitial radiofrequency therapy vs transurethral resection of the prostate. Semmens J, Wisniewski Z, Bass A et al: Trends in repeat prostatectomy after surgery for benign prostate disease: application of record linkage to healthcare outcomes. Helfand B, Mouli S, Dedhia R et al: Management of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia with open prostatectomy: results of a contemporary series. Condie J, Jr, Cutherell L et al: Suprapubic prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia in rural Asia: 200 consecutive cases. Tubaro A, Carter S, Hind A et al: A prospective study of the safety and efficacy of suprapubic transvesical prostatectomy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Hill A, Njoroge P: Suprapubic transvesical prostatectomy in a rural Kenyan hospital. Gacci M, Bartoletti R, Figlioli S et al: Urinary symptoms, quality of life and sexual function in patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy before and after prostatectomy: a prospective study. Adam C, Hofstetter A, Deubner J et al: Retropubic transvesical prostatectomy for significant prostatic enlargement must remain a standard part of urology training. Varkarakis I, Kyriakakis Z, Delis A et al: Long-term results of open transvesical prostatectomy from a contemporary series of patients. Sotelo R, Spaliviero M, Garcia-Segui A et al: Laparoscopic retropubic simple prostatectomy. Hurle R, Vavassori I, Piccinelli A et al: Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate combined with mechanical morcellation in 155 patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Kuntz R, Lehrich K: Transurethral holmium laser enucleation versus transvesical open enucleation for prostate adenoma greater than 100 gm. Gilling P, Cass C, Cresswell M et al: Holium laser resection of the prostate: preliminary results of a new method for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Gilling P, Mackey M, Cresswell M et al: Holmium laser versus transurethral resection of the prostate: a randomized prospective trial with 1-year followup. Fu W, Hong B, Yang Y et al: Photoselective vaporization of the prostate in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Malek R, Kuntzman R, Barrett D: Photoselective potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vaporization of the benign obstructive prostate: observations on long-term outcomes. Saporta L, Aridogan I, Erlich N et al: Objective and subjective comparison of transurethral resection, transurethral incision and balloon dilatation of the prostate. Reihmann M, Knes J, Heisey D et al: Transurethral resection versus incision of the prostate: a randomized, prospective study. Wasson J, Reda D, Bruskewitz R et al: A comparison of transurethral surgery with watchful waiting for moderate symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Baumert H, Ballaro A, Dugardin F et al: Laparoscopic versus open simple prostatectomy: a comparative study. The expert Panel examined three overarching key questions for pharmacotherapeutic, surgical, and alternative medicine therapies: 1. What are the adverse events associated with each of the included treatments and how do the adverse events compare across treatments Are there subpopulations in which the efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse event rates vary from those in general populations Efficacy measures the extent to which an intervention produces a beneficial result under ideal conditions, such as clinical trials, whereas effectiveness measures the extent to which an intervention in ordinary conditions produces the intended result. All titles and abstracts from the bibliographic searches were reviewed by the Panel chair and the co-chair and the relevant articles were selected and then the full-text reviewed for inclusion. To update the search from January 2007 through February 2008, titles, abstracts and full-text were dual reviewed by either the Panel chair or co-chair and the methodologist, and consensus was achieved at the full-text level. The Panel chair and co-chair selected outcomes for abstraction and synthesis that were relevant to the clinician such as urinary flow and volume outcomes, as well as outcomes important to patients, such as symptoms and QoL. Also abstracted were data on adverse events for both pharmacotherapy and procedural interventions. For the latter, intraoperative, peri-operative, as well as short-term (<30 days) and longer-term adverse events were examined. Studies with an included other, including the strategy of watchful intervention compared to waiting. Different techniques for the same surgical intervention not included in procedure will be compared this 3. Significant morbidity Setting There were no restrictions based on geographic location of the study or on other study setting characteristics. Key Question 3: Subpopulations: study designs as noted above Minimum duration of follow-up 1. Studies with an English characteristics English abstract but non-English full text 2. Data Synthesis A qualitative analysis of the available evidence was performed on all interventions and outcomes. A narrative synthesis was presented, along with in-text tables summarizing important study and population characteristics, outcomes and adverse events. Forest plots of study effect sizes were prepared when there were at least three to four points for an intervention. Meta-analyses (quantitative synthesis) of outcomes of randomized controlled trials were planned; however, data were either sparse. The studies varied with respect to patient selection; randomization; blinding mechanism; run-in periods; patient demographics, comorbidities, prostate characteristics, and symptoms; drug doses; other intervention characteristics; comparators; rigor of follow-up; follow-up intervals; trial duration; timing of the trial; suspected lack of applicability to current practice in the United Sates; and techniques of outcomes measurement. Thus, the Panel and extractors were required to review the material in a systematic fashion rather than one with statistical rigor. Detailed efficacy, effectiveness and complications outcomes are found in Chapter 3 of the guideline. As in the previous Guideline, the guideline statements were graded with respect to the degree of flexibility in their application. Standard: A guideline statement is a standard if: (1) the health outcomes of the alternative interventions are sufficiently well known to permit meaningful decisions and (2) there is virtual unanimity about which intervention is preferred. Options can exist because of insufficient evidence or because patient preferences are divided and may/should influence choices made. A full description of the methodology is presented in Chapter 2 of this guideline. It speaks to diagnostic tests available to identify the underlying pathophysiology and help management of symptoms. The current literature for standard surgical options, as well as that on minimally invasive procedures is similarly reviewed. In some situations, the Panel, not surprisingly, was forced to recommend best practices based on expert opinion. A qualitative analysis of the available evidence was performed on all interventions and outcomes. A narrative synthesis was presented along with in-text tables summarizing important study and population characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness outcomes and safety outcomes. Studies were stratified by study design, comparator, follow-up interval and intensity of intervention. The studies varied with respect to patient selection; randomization; blinding mechanism; run-in periods; patient demographics, comorbidities, prostate characteristics and symptoms; drug doses; other intervention characteristics; comparators; rigor of follow-up; follow-up intervals; trial duration; timing of the trial; suspected lack of applicability to current practice in the United Sates; and techniques of outcomes measurement. These data limitations affected the quality of the materials available for review, making formal meta-analysis impractical or futile. The resulting evidence tables for each treatment alternative evaluated are presented in Appendix A8.

Purchase tofranil with a visa. Social Anxiety Affirmations | Daily Affirmations To Stop Social Anxiety.

Syndromes

- Multiple system atrophy

- Echocardiogram to check for heart defects (usually done soon after birth)

- Urine amino acid test

- Clubbing (thickening of the nail beds) on toes and fingers (late sign)

- Bleeding

- Argininosuccinic aciduria

- Prostate cancer

- National Kidney Disease Education Program - www.nkdep.nih.gov

- If you have had a recent or past infection such as mononucleosis or viral hepatitis

- 1 to 3 years: 6 mg/day

The strategy of community-based rehabilitation has been implemented in many low income countries around the world and has successfully inuenced the quality of life and participation of persons with disabilities in societies where it is in practice anxiety network generic 50mg tofranil with mastercard. A wide range of rehabilitation interventions anxiety 4th 9904 generic tofranil 75mg with visa, intervention programmes and services has been shown to contribute effectively to the optimal functioning of people with neurological conditions anxiety symptoms of going crazy purchase tofranil 75mg free shipping. He needs an assistive communication device he has no way of leaving his house to access community which is not provided by the health system and is not pos facilities anxiety worksheets buy tofranil 50mg without prescription, he cannot return to his previous job anxietyzone symptoms poll purchase tofranil mastercard, and he has sible for his family to purchase anxiety rings purchase 25mg tofranil fast delivery, so his family made a basic no relocation option in view. Behavioural problems can also become evident when the person affected realizes the severity of his or her limitations, and the fact that they may be permanent. Finally, on his own, Juan adapted his ered well from his physical limitations, except for a total tools to be able to function as a shoe-shiner in a park. At paralysis of his right arm and uncoordinated movements of his last appointment, he was newly wed and attended with his left arm and legs. He was nally happy with himself and ing medical treatment for his former addiction problem. Stigmatization of certain diseases and conditions is a universal phenomenon that can be seen across all countries, societies and populations. Important exceptions are epilepsy and dementia: stigma plays an important role in forming the social prognosis of people with these disorders. Stigma leads to direct and indirect discriminatory behaviour and factual choices by others that can substantially reduce the opportunities for people who are stigmatized. Stigma increases the toll of illness for many people with brain disorders and their families; it is a cause of disease, as people Box 1. Disruptiveness the degree of strain and difficulty stigma adds to interpersonal relationships. Moreover, stigmati zation is frequently irreversible so that, even when the behaviour or physical attributes disappear, individuals continue to be stigmatized by others and by their own self-perception. One of the most damaging results of stig matization is that affected individuals or those responsible for their care may not seek treatment, hoping to avoid the negative social consequences of diagnosis. Epilepsy carries a particularly severe stigma because of misconceptions, myths and stereo types related to the illness. In some communities, children who do not receive treatment for this disorder are removed from school. These mis conceptions cause people to retreat in fear from someone having a seizure, leaving that person unprotected from open res and other dangers they might encounter in cramped living conditions. Recent research has shown that the stigma people with epilepsy feel contributes to increased rates of psychopathology, fewer social interactions, reduced social capital, and lower quality of life in both developed and developing countries (22). Efforts are needed to reduce stigma but, more importantly, to tackle the discriminatory attitudes and prejudicial behaviour that give rise to it. Fighting stigma and discrimination requires a multilevel approach involving education of health professionals and public information campaigns to educate and inform the community about neurological disorders in order to avoid common myths and promote positive attitudes. Methods to reduce stigma related to epilepsy in an African community by a parallel operation of public education and comprehensive treatment programmes successfully changed attitudes: traditional beliefs about epilepsy were weakened, fears were diminished, and community acceptance of people with epilepsy increased (24). Governments can reinforce efforts with laws that protect people with brain disorders and their families from abusive practices and prevent discrimination in education, employment, housing and other opportunities. Legislation can help, but ample evidence exists to show that this alone is not enough. The emphasis on the issue of prejudice and discrimination also links to another concept where the need is to focus less on the person who is stigmatized and more on those who do the stigma tizing. The role of the media in perpetrating misconceptions also needs to be taken into account. Stigmatization and rejection can be reduced by providing factual information on the causes and treatment of brain disorder; by talking openly and respectfully about the disorder and its effects; and by providing and protecting access to appropriate health care. To reduce the global burden of neurological disorders, an adequate focus is needed on training, especially of primary health workers in countries where neurologists are few or nonexistent. Training manuals tailored to the needs of specic countries or regions must be developed. Primary care providers need to be trained to recognize the need for referral to more specialized treatment rather than trying to make a diagnosis. Training of physicians the points to be taken into consideration in relation to education in neurology for physicians include: core curricula (undergraduate, postgraduate and others); continuous medical education; accreditation of training courses; open facilities and international exchange programmes; use of innovative teaching methods; training in the public health aspects of neurology. The central idea is to build both the curriculum and an examination system that ensure the achievement of professional competence and social values and not merely the retention and recall of information. This is not necessarily undesirable because the curriculum must take into account local differences in the prevalence of neurologi cal disorders. Some standardization in the core neurological teaching and training curricula and methods of demonstrating competency is desirable, however. Continuous medical education is an important way of updating the knowledge of specialists on an ongoing basis and providing specialist courses to primary care physicians. Therefore training in public health, service delivery and economic aspects of neurological care need to be stressed in their curricula. The use of modern technology facilities and strategies such as distance-learning courses and telemedicine could be one way of decreasing the cost of training. It is a comprehensive approach that is con cerned with the health of the community as a whole. Specialist neurologists usually treat individual patients for a specic neurological disorder or condition; public health professionals approach neurology more broadly by monitoring neurological disorders and related health concerns in entire communities and promoting healthy practices and behaviours so as to ensure that populations stay healthy. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, 1946. Preventive medicine for the doctor in his community: an epidemiological approach, 3rd ed. Disabled village children: a guide for health workers, rehabilitation workers and families. Information on relative 30 Data presentation burden of various health conditions and risks to health is an important element in strategic 37 Conclusions health planning. The main purpose was to convert partial, often widely used frameworks for information on summary measures nonspecic, data on disease and injury occurrence of population health across disease and risk categories. Government and nongovernmental agencies alike have used these results to argue for more strategic allocations of health resources to disease prevention and control programmes that are likely to yield the greatest gains in terms of population health. These socioeconomic variables show clear historical relationships with mortality rates, and may be regarded as indirect, or distal, determinants of health. Mortality estimates were based on analysis of latest available national information on levels of mortality and cause distributions as at late 2003. Uncertainty in projections has been addressed not through an attempt to estimate uncertainty ranges, but through preparation of pessimistic and optimistic projections under alternative sets of input assumptions. The results depend strongly on the assumption that future mortality trends in poor countries will have the same relationship to economic and social development as has occurred in higher income countries in the recent past. If this assumption is not correct, then the projections for low income countries will be over-optimistic in the rate of decline of communicable and noncommuni cable diseases. If broad trends in risk factors are towards worsening of risk exposures with development, rather than the improvements observed in recent decades in many high income countries, then again the projections for low and middle income countries presented here will be too optimistic. It also lists the sequelae analysed for each cause category and provides relevant case denitions. Dashed lines represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The higher burden is also a reection of a higher percentage of population in low and lower middle income countries. They help in identifying not only the fatal but also the nonfatal outcomes for diseases that are especially important for neurological disorders. As a group they cause a much higher burden than digestive diseases, respiratory diseases and malignant neoplasms. In absolute terms, since most of the burden attributable to neu rological disorders is in low and lower middle income countries, international efforts need to concentrate on these countries for maximum impact. Some of the impact on poor people includes the loss of gainful employment, with the attendant loss of family income; the requirement for caregiving, with further potential loss of wages; the cost of medications; and the need for other medical services. The above analysis is useful in identifying priorities for global, regional and national attention. Traditionally, the allocation of resources in health organizations tends to be conducted on the basis of historical patterns, which often do not take into account recent changes in epidemiology and relative burden as well as recent information on the effectiveness of interven tions. A population-level analysis of cost-effectiveness of rst-line antiepileptic drug treatment is illustrated in the discussion on epilepsy (Chapter 3. Aspirin is the most cost-effective intervention both for treating acute stroke and for preventing a recurrence. The disease specic sections discuss in detail the various public health issues associated with neurological disorders. This chapter strengthens the evidence provided earlier that increased resources are needed to improve services for people with neurological disorders. It is also hoped that analyses such as the above will be adopted as an essential component of decision-making and will be adapted to planning processes at global, regional and national levels, so as to utilize the available resources more efficiently. The global burden of disease in 1990: summary results, sensitivity analyses, and future directions. For the most part, altering the pro gressive course of the disorder is unfortunately not possible. Alzheimer and other dementias have been reliably identied in all countries, cultures and races in which systematic research has been carried out, though levels of awareness vary enormously. In India, for example, while the syndrome is widely recognized and named, it is not seen as a medical condition. For the purpose of making a diagnosis, clinicians focus in their assessments upon impairment in memory and other cognitive functions, and loss of independent living skills. Common psychological symptoms include anxiety, depression, delusions and hallucinations. Single gene mutations at one of three loci (beta amyloid precursor protein, presenilin1 and presenilin2) account for most of these cases. A common genetic polymor phism, the apolipoprotein E (apoE) gene e4 allele greatly increases risk of going on to suffer from dementia; up to 25% of the population have one or two copies (4, 5). However, it is not uncommon for one identical twin to suffer from dementia and the other not. Depression is a risk factor in short-term longitudinal studies, but this may be because depression is an early presenting symptom rather than a cause of dementia (11). This may be because some environmental risk factors are much less prevalent in these settings. Conversely, some risk factors may only be apparent in developing countries, as they are too infrequent in the developed economies for their effects to be detected; for example, anaemia has been identied as a risk factor in India (16). This happens in a small number of cases in the developed world, but could be more common in developing countries, where relevant underlying physical conditions (including marked nutritional and hormonal deciencies) are more common. Its impact can depend on what the individuals were like before the disease: their personality, lifestyle, signicant relationships and physical health. The problems linked to dementia can be best understood in three stages (see Box 3. At the same time, one must not alarm people in the early stages of the disease by giving them too much information. Evidence from well-conducted, representative epidemiological surveys was lacking in many regions. Most people with dementia live in developing countries: 60% in 2001 rising to an estimated 71% by 2040. The person may: disease is gradual, it is difficult to especially of recent events and have difficulty eating be sure exactly when it begins. There is a clear and general tendency for prevalence to be somewhat lower in developing countries than in the industrialized world (18), strikingly so in some studies (19, 20). It does not seem to be explained merely by differences in survival, as estimates of incidence are also much lower than those reported in developed countries (21, 22).

References

- Chamberlain RS, Canes D, Brown KT, et al. Hepatic neuroendocrine metastases: does intervention alter outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:432-445.

- Hall JW 3rd, Brown DP, Mackey-Hargadine JR. Pediatric applications of serial auditory brainstem and middle-latency evoked response recordings. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1985;9(3):201-218.

- Naider, M., Ramesh, K., Anuradha, R. et al. (1991). Evaluations of phenytoin in rheumatoid arthritis: An open study. Drugs under Experimental and Clinical Research, 17, 71n275.

- Alken P: The telescope dilators, World J Urol 3:7-10, 1985.

- Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. A subpopulation of apoptosis-prone cardiac neural crest cells targets to the venous pole: multiple functions in heart development? Dev Biol 1999;207:271-286.