David Ashley, MBBS, PhD

- Professor of Neurosurgery

- Rory David Deutsch Distinguished Professor of Neuro-Oncology

- Professor of Medicine

- Professor in Pediatrics

- Professor in Pathology

- Member of the Duke Cancer Institute

https://medicine.duke.edu/faculty/david-ashley-mbbs-phd

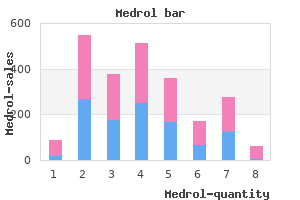

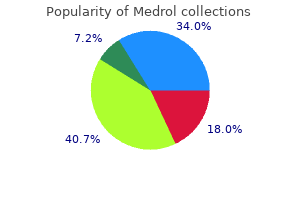

Intervention: the intervention group followed a 6-month physical Children activity stimulation program involving counselling through motivational interviewing rheumatoid arthritis presentation purchase medrol canada, home-based physiotherapy arthritis in fingers nodules generic medrol 16mg amex, and 4 months of tness training arthritis in dogs licking cheap medrol line. Outcome measures: Primary outcomes were walking activity (assessed objectively with an activity monitor) and parent-reported physical activity (Activity Questionnaire for Adults and Adoles cents) arthritis medication lung damage discount medrol 4 mg without a prescription. Results: There were no signi cant intervention effectsforphysicalactivityorsecondaryoutcomesatanyassessmenttime arthritis in the knee treatment exercises buy medrol 16 mg without a prescription. Positivetrendswerefoundfor parent-reported time at moderate-to-vigorous intensity (between-group change ratio=2 signs of arthritis in feet and legs purchase 4mg medrol amex. Conclusions: this physical activity stimulation program, that combined tness training, counselling and home-based therapy, was not effective in children with cerebral palsy. Further research should examine the potential of each component of the intervention for improving physical activity in this population. Introduction adulthood, 6 it is important to intervene at an early stage to prevent school-age children with cerebral palsy from becoming even less Maintaining physical activity is especially important for chil active during adolescence. A combination of tness baseline; at 4 months (ie, at the end of tness training, when only training and physical activity counselling may interrupt the vicious walking capacity, functional strength and tness were assessed); at cycle of deconditioning in people with disabilities. Design Intervention this multi-centre, parallel-group randomised controlled trial the intervention group followed the physical activity stim with concealed allocation and blinded assessments was conducted ulation program, which involved a lifestyle intervention and in paediatric physiotherapy practices and special schools for chil tness training followed by usual physiotherapy. The control group dren with disabilities in the Netherlands between September 2009 undertook only usual physiotherapy. In a previous publication we described the ventions are presented in Figure 1 and described in more detail study design extensively. Participants coachthechildrenandtheparentstoadoptmoreactivelifestyles, as were randomised 1:1 to the experimental or control intervention, well as home-based physiotherapy. Participants were informed interview technique is that the client indicates which goals are fea of group allocation following the baseline assessments. As a vention group followed a 6-month physical activity stimulation minimum, the coordinating researcher initiated three counselling program, involving a lifestyle intervention and 4 months of t sessions. The control group continued their usual paediatric Home-based physiotherapy, aimed at increasing the capacity for physiotherapy. Outcomes were assessed in the hospital: at daily activities in a situation relevant for the children, was tailored Group Component Month 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Exp Fitness training Motivational interviewing Home-based physiotherapy Usual physiotherapy Con Usual physiotherapy Exp = experimental group, Con = control group. Design of the experimental (physical activity stimulation program) and control group interventions. The t ber of lateral step-ups (left and right leg) and sit-to-stands ness training program was aimed at increasing lower-extremity achieved during 30seconds. On the same cycle ergometer, children ing children to start participating in other physical activities during performed the 20-second Wingate sprint test to determine mean the intervention, as a result of the counselling. For each training session physiotherapists recorded the sport clubs (seven statements), and the attitudes of the parents training load, the number of sets and repetitions of the exercises, and immediate family members towards the importance of sports and any adverse events. Walking height and weight were measured, and several family character activity was assessed for 1 week using an ankle-worn bi-axial istics were determined (siblings, parental marital status, parental accelerometer, a which registered accelerations in the frontal and educational level and sports frequency of the immediate fam sagittal plane at regular time intervals. Selective motor control was assessed with the modi ed Trost calibration, as previously described, 18 the accelerometer can test, during which the ability of children to dorsi ex the ankle accurately record strides (ie, complete gait cycles) for chil and extend the knee in an isolated movement was scored in four dren with cerebral palsy by measuring the steps of one leg. Parents also indicated the sports frequency of immedi were calculated in minutes. All representative days were used ate family members in ve categories (from 1=never to 5=daily), to calculate averages for schooldays, and weighted total values from which a mean score was calculated. Children then completed re ecting an average weekday, based on schooldays and week mobility capacity assessments and tness tests, after which the ca end days. Parent-reported physical activity was assessed using the librated accelerometer was provided to register walking activity child-adapted Activity Questionnaire for Adults and Adolescents for one week. Parents also indicated needed in each group to detect a clinically relevant difference of whether their child was being physically active as part of sports 1000 strides per day between groups. To allow for 10% loss to follow-up, 25 children the secondary outcomes included: mobility capacity (gross were included in each group. To correct for performing statistical Research 43 tests over multiple time points, the critical p-value was divided transformed back, providing a between-group change ratio. Variables with non-normally trol and sport frequency of the immediate family were included distributed residuals were logarithmically transformed prior to as covariates in the analyses when they changed the intervention performing linear regression analyses, after which the results were effect by more than 10%. Children with cerebral palsy assessed for eligibility (n = 110) Excluded (n = 60) Not interested (n = 22)a Too busy to participate (n = 24) Language or logistical problems (n = 7) Planned botulinum toxin treatment (n = 4) Wrong address; did not reply (n = 2) No diagnosis of cerebral palsy (n = 1) Signed informed consent and randomised (n = 50) 1 child signed informed consent, but dropped out before baseline, due to unexpected botulinum toxin treatment Measured physical activity, mobility capacity, fitness, fatigue, attitude towards sports Baseline (n = 25) (n = 24) Intervention group Control group Lost to follow-up counselling no counselling Lost to follow-up medical reason (n = 1) home-based no home-based medical reasons (n = 1) unmotivated to continue physiotherapy physiotherapy intervention (n = 1) fitness training (anaerobic usual exercises, muscle physiotherapy strength) Month 4 Measured one-minute walk test, functional muscle strength, and fitness only (n = 23) (n = 23) Intervention group Control group counselling no counselling home-based no home-based physiotherapy physiotherapy usual physiotherapy Month 6 Measured physical activity, mobility capacity, fitness, fatigue, attitude towards sports (n = 23) (n = 23) Intervention group Control group no counselling no counselling Lost to follow-up no home-based physiotherapy no home-based did not attend (n = 1) usual physiotherapy physiotherapy usual physiotherapy Month 12 Measured physical activity, mobility capacity, fitness, fatigue, attitude towards sports (n = 23) (n = 22) Figure 2. After taking rest (omitting two training sessions) and reduction of the training intensity, she was able In total, 110 children with cerebral palsy were invited to par to resume and complete the training program. Fifty children agreed, signed an cessful, with the assessor correctly guessing group allocation at informed consent form and were randomised to either the exper a rate similar to chance throughout the trial. Children were treated not complete all assessments on each occasion due to motivational at 13 paediatric physiotherapy practices (n=27) and three special problems or time constraints, as illustrated by the number of ana schools for children with disabilities (n=23). One child at 6 months, and four children group)droppedoutbeforebaselineassessmentsduetounexpected at 12 months did not wear the accelerometer. Three children (experimental group: n=2, control group: n=1) dropped out during the rst 4 months of Effect of intervention the intervention, and one child (control group) missed the 4-month and 12-month assessments. A trend in favour of the intervention group was identi ed at 6 months for parent-reported time at moderate-to Compliance with the trial method vigorous intensity (between-group change ratio 2. The families in the experimental group received a median of ve counselling sessions (range three to nine). An inventory of previously experienced mobility-related problems resulted in Secondary outcomes home-based physiotherapy for 14 of the 23 children in the experi No signi cant intervention effect was demonstrated for mobil mental group. For attitude the fourth to the last week according to the protocol, by reducing towardssports, whencomparedtothecontrolgroup, therewasalso the work:rest ratio from 1:4 to 1:3 when performing ve sets of a trend for reporting greater agreement with possible advantages Table 1 Characteristics of participants. Outcome Groups Difference between groupsa Difference between groupsa Baseline Month 6 Month 12 Month 6 minus baseline Month 12 minus baseline Month 6 minus Month 12 baseline minus baseline Exp Con Exp Con Exp Con Exp Con Exp Con Exp minus Con Exp minus Con Average weekday (n=23) (n=22) (n=20) (n=20) (n=19) (n=20) (n=20) (n=19) (n=19) (n=19) Strides (n/day) 5109 (1636) 5181 (1758) 5314 (2250) 6012 (1746) 4746 (1750) 4868 (1557) 268 (1108) 725 (1591) 162 (1312) 146 (1827) 858 (1819 to 104) 175 (1218 to 867) Medium to high stride rate 123 (43) 127 (49) 128 (59) 148 (48) 110 (45) 114 (40) 7 (31) 19 (44) 8 (36) 8 (49) 23 (50 to 3) 5 (31 to 22) (minutes/day) High stride rate 49 (22) 49 (23) 55 (37) 65 (26) 45 (24) 50 (25) 7 (22) 15 (26) 0 (21) 3. Table 3 Group averages for parent-reported physical activity for each group, difference within groups, and difference between groups. The intervention effect was not substantially confounded by age, sex, or selective motor control. Since changing physical activity behaviour is a complex pro Discussion cess, evaluatingtheeffectofthismulti-componentphysicalactivity stimulation program on other outcomes may provide valuable There was no signi cant effect of the intervention on phys information. Because the tness training incorporated gross motor ical activity, so the hypothesis that counselling, home-based activities, and the home-based physiotherapy was focused on physiotherapy and tness training would work synergistically practising mobility activities in the home, we expected that mobil to improve physical activity could not be con rmed. Although no signi cant effects of against our expectations, previous studies in cerebral palsy showed intervention were demonstrated, the positive trend for gross (non-signi cant) positive trends towards improving physical activ motor capacity, which is a highly relevant outcome measure in ity in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy after either this population, shows that this home-based activity approach counselling, 11 or tness training only. No evidence has been group seems substantial, since it exceeds the minimum clinical found for the effectiveness of family-based and community-based important difference reported by Oef nger et al33 No conclu physical activity interventions that combine exercise programs sions could be drawn about which component of the intervention with the provision of information. However, it is out that physical activity among typically developing children most likely that the individually tailored home-based physio can be increased by means of school-based interventions. This is supported by with positive effects on physical activity were characterised by the positive trend found for the 1-minute walk test, directly after a multicomponent intervention (education, focus on behavioural ending the tness program. Although two components of the change and involvement of parents) and a minimum intervention program may have potential to improve mobility capacity, the duration of one school year. Therefore, it is possible that our 6 added value of improving mobility capacity for increasing physi month program was too short to elicit changes in such a complex cal activity remains unclear. The reduction was planned to ical activity might be insuf cient contrast between groups, which limit the burden on parents and children, and to allow the chil could arise from three possible sources. First, the families who dren to develop physical activities in order to create a transitional chose to participate in the study were likely to be more inter period between the organised tness training and self-developed ested in (increasing) physical activity than those who refused to activities. This selection bias may have ceed in initiating further physical activities, resulting in insuf cient resulted in all families in the study stimulating physical activity of training volume to elicit a signi cant tness improvement. Second, physiothera ever, the bene cial effect of a higher tness training volume on pists participating in the study were interested in tness training physical activity is not yet clear. Possibly, they (unintentionally) ing program of four times per week only resulted in a positive trend changed the content of the physiotherapy treatment for the control in physical activity, despite an effect on tness. However, the small effect sizes for attitude towards sports in our the two measures of physical activity demonstrated contrast population, which is already very positive about sports, weaken the ing results: there was no change for walking activity assessed clinical relevance of these improvements. Also, envi but does not provide information about other types of activ ronmental barriers, such as lack of transportation and availability ities performed. However, self-reports are prone to recall improving physical activity should assess the presence of environ bias and socially desired answering. Physical motivational skills and training facilities might have in uenced the activity for the chronically ill and disabled. Dev Med Child In conclusion, a physical activity stimulation program combin Neurol. Aerobic capacity in children and adolescents with physiotherapy and tness training was not effective for increasing cerebral palsy. Ambulatory physical activity performance in youth with cerebral palsy and youth who are develop nent of the program for improving physical activity. Gross motor capability and bral palsy have lower levels of physical activity and tness performance of mobility in children with cerebral palsy: a comparison across compared to their typically developing peers. Activity, activity, activity: rethinking our physical therapy approach to cerebral palsy. Studies of interventions to promote physical activity in school children with spastic cerebral palsy: effects on daily activity, fat mass this population have shown favourable, but non-signi cant, and tness. What this study adds: A physical activity stimulation Exercise training program in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a program consisting of tness training, counselling and home randomized controlled trial. An internet-based physical activity based therapy was not effective in children with cerebral palsy. Home programmes in paediatric occupational ther apy for children with cerebral palsy: where to start Grant providers were not involved in muscle strength and mobility in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, manuscript controlled trial. Dev Med Child Source(s) of support: this project is part of the Dutch national Neurol. Validity of a 1minute walk test for therapists of the paediatric physiotherapy practices (Kinderfysio children with cerebral palsy. Reliability of hand-held dynamometry and functional strength tests Bos-Lunnemann Fysiotherapiepraktijk, Fysiotherapie Hoep-Zuid, for the lower extremity in children with cerebral palsy. Intrasession and intersession reliability piepraktijk Het Rendier, Fysiotherapie Zwanenlaan, Fysiothera of handheld dynamometry in children with cerebral palsy. Cross-validation of the 20 Tuindorp Oostzaan, Gezondheidscentrum Holendrecht, Maatschap versus 30-s Wingate anaerobic test. Assessment of physical torial validity and invariance of questionnaires measuring social-cognitive activity in youth. Identi cationoffacilitatorsand Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and tness in chil barriers to physical activity in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Short Definitions of Different Types of Questions Intervention/Therapy: Questions addressing the treatment of an illness or disability. Diagnosis: Questions addressing the act or process of identifying or determining the nature and cause of a disease or injury through evaluation. Prognosis/Prediction: Questions addressing the prediction of the course of a disease. Sample Questions: Intervention: In African-American female adolescents with hepatitis B (P), how does acetaminophen (I) compared to ibuprofen (C) affect liver function (O) Therapy: In children with spastic cerebral palsy (P), what is the effect of splinting and casting(I) compared to constraint induced therapy (C) on two-handed skill development (O) Prognosis/Prediction: 1) For patients 65 years and older (P), how does the use of an influenza vaccine (I) compared to not received the vaccine (C) influence the risk of developing pneumonia (O) during flu season (T) Etiology: Are 30 to 50-year-old women (P) who have high blood pressure (I) compared with those without high blood pressure (C) at increased risk for an acute myocardial infarction (O) during the first year after hysterectomy (T) Meaning: How do young males (P) with a diagnosis of below the waist paralysis (I) perceive their interactions with their romantic significant others (O) during the first year after their diagnosis (T) Cerebral palsy is a descriptive term for a problem of motor control caused by an irreversible structural difference or damage to the brain that happens before birth, around the time of birth or in the first 2 years of life. Although the brain injury does not get any worse as the child gets older, the difficulties it causes can change in the growing child.

Diseases

- Chronic spasmodic dysphonia

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Rhabdomyosarcoma 1

- Functioning pancreatic endocrine tumor

- Chromosome 4, trisomy 4q21

- Localized epiphyseal dysplasia

- Campylobacteriosis

- AIDS

- Hereditary amyloidosis

Patients with progressive disease on chemotherapy are not suitable candidates for secondary cytoreduction arthritis in fingers in 20s proven 4mg medrol, but patients with recurrent disease are occasionally candidates for surgical excision of their disease arthritis relief in knees 4 mg medrol. Complete resection is possible when there are only one or two isolated recurrences in patients without diffuse carcinomatosis (258) arthritis pain associates pg county purchase 16mg medrol with amex. Chemotherapy for Persistent-Recurrent Ovarian Cancer the majority of women who relapse will be offered more chemotherapy with the likelihood of benefit related to the initial response and the duration of response arthritis in neck dizziness medrol 4 mg without prescription. The goals of treatment include improving control of disease-related symptoms oa arthritis diet purchase cheap medrol line, maintaining or improving quality of life arthritis diet changes buy 4 mg medrol visa, delaying time to progression, and possibly prolonging survival, particularly in women with platinum-sensitive recurrences. Many active chemotherapy agents (platinum, paclitaxel, topotecan, liposomal doxorubicin, docetaxel, gemcitabine, and etoposide) and targeted agents (bevacizumab) are available, and the choice of treatment is based on many factors including likelihood of benefit, potential toxicity, and patient convenience. Patients who relapse within 6 months of completing first-line chemotherapy are classified as platinum-resistant and have a median survival of 6 to 9 months and a 10% to 30% likelihood of responding to chemotherapy. Patients who progress while on treatment are classified as having platinum-refractory disease. The potential adverse effects associated with chemotherapy in trials in women with recurrent ovarian cancer are well documented and should not be underestimated. The reported adverse effects associated with paclitaxel were alopecia in 62% to 100%, neurotoxicity (any grade) in 5% to 42% of patients, and severe leukopenia in 4% to 24% of patients. Topotecan is associated with significantly greater myelosuppression than liposomal doxorubicin or paclitaxel and is observed in 49% to 76% of patients. In both trials, a significant proportion of the patients did not receive paclitaxel as part of their initial chemotherapeutic regimen. The absolute 2-year survival advantage was 7% (57% versus 50%), and there was a 5-month improvement in median survival (29 versus 24 months). The toxicities were comparable, except for a significantly higher incidence of neurologic toxicity and alopecia in the paclitaxel group, while myelosuppression was significantly greater with the non-paclitaxel containing regimens. These data support the slight advantage of a second-line regimen containing both paclitaxel and a platinum agent compared with platinum-based therapy alone in patients who have not received paclitaxel in their primary chemotherapeutic regimen. There were two randomized trials comparing carboplatin alone to carboplatin and gemcitabine or liposomal doxorubicin (294, 295). There was a higher response rate with the combination therapy and a longer progression-free survival, but the studies were not powered to look at overall survival. Platinum-Resistant and Refractory Disease Patients with platinum-refractory and resistant ovarian cancer are treated with chemotherapy and may have a number of lines of therapy depending on response and performance status. Single-agent therapy is typically used because combination regimens are associated with more toxicity without any apparent additional benefit. There are a variety of potentially active drugs: paclitaxel, docetaxel, topotecan, liposomal doxorubicin, gemcitabine, oral etoposide, tamoxifen, and bevacizumab are the most frequently used. The results of a study comparing topotecan with liposomal doxorubicin demonstrate the low response rates and poor prognosis among women with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (265). There were two randomized trials comparing liposomal doxorubicin with either topotecan or paclitaxel. In a study of 237 women who relapsed after receiving one platinum-containing regimen, 117 of whom (49. The two treatments had a similar overall response rate (20% versus 17%), time to progression (22 versus 20 weeks), and median overall survival (66 versus 56 weeks). The myelotoxicity was significantly lower in the liposomal doxorubicin-treated patients than with those receiving topotecan. In a second study comparing liposomal doxorubicin with single-agent paclitaxel in 214 platinum-treated patients who had not received prior taxanes, the overall response rates for liposomal doxorubicin and paclitaxel were 18% versus 22%, respectively, and median survival durations were 46 and 56 weeks, respectively, and these were not significantly different (266). In practice, most patients are treated with a starting dose of 40 mg/m of liposomal doxorubicin every 4 weeks, because of the toxicity2 associated with the higher dose and the need to dose reduce when 50 mg/m is used. In2 a subset analysis of platinum-resistant patients, the median time to progression ranged from 9. It is not known whether the treatment improved symptoms control or quality of life because this was not specifically addressed. None of the efficacy end points showed a statistically significant difference between treatment groups. Some researchers attempted to treat patients with non-platinum drugs to prolong the platinum-free interval, hoping that would allow the tumor to become platinum-sensitive during the interval use of non-cross-resistant agents. The rationale for this approach is the belief that the platinum-free interval is equivalent to the treatment-free interval, and before the availability of other active drugs, these two terms were synonymous. There are no data to support the hypothesis that the interposition of another drug can produce an increased platinum sensitivity as a result of a longer interval since the last platinum treatment. Weekly paclitaxel is active, and the toxicity, especially myelosuppression, is less than with the every 3-week regimens. Although there was a 22% objective response rate, the median response duration was only 2. With the 5-day dosing schedule, approximately 70% to 80% of patients have severe neutropenia, and 25% have febrile neutropenia with or without infection. In some studies, regimens of 5 days produce better response rates than regimens of shorter duration, but in others, reducing the dose to 1. In a study of 31 patients, one-half of whom were platinum refractory, topotecan 2 mg/m per day for 3 days every 21 days had a 32% response rate2 (285). Weekly topotecan administered at a dose of 4 mg/m per week for 3 weeks with a2 week off every month produced a response rate similar to the 5-day regimen with considerably less toxicity, and this is the preferred dose schedule in the recurrent setting (290). Oral topotecan, not available in the United States, results in similar response rates with less hematologic toxicity (286). The intravenous and oral formulations of topotecan were compared in a randomized trial of 266 women as a third-line regimen after an initial platinum-based regimen (291). One of the most important side effects of liposomal doxorubicin is the hand-foot syndrome, also known as palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia or acral erythema, which occurs in 20% of patients who receive 50 mg/m every 4 weeks2 (266). Most oncologists administer 40 mg/m and escalate only if there are no side effects. In a study of 89 patients with platinum-refractory disease, including 82 paclitaxel-resistant patients, liposomal doxorubicin (50 mg/m every 32 weeks) produced a response in 17% (1 complete and 14 partial responses) (268). In another study, an objective response of 26% was reported, although there were no responses in women who progressed during first-line therapy (265). The drug is used in doublet combinations with cisplatin or carboplatin with acceptable responses and toxicities, and in the triplet combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel (304). Oral Etoposide the most common toxicities with oral etoposide are myelosuppression and gastrointestinal: grade 4 neutropenia is observed in about one-fourth of patients, and 10% to 15% have severe nausea and vomiting (307, 308). A study of oral etoposide given for a prolonged treatment (50 mg/m daily for 21 days every 4 weeks) had a 27%2 response rate in 41 women with platinum-resistant disease, 3 of whom had durable complete responses (308). In 25 patients with platinum and taxane-resistant disease, 8 objective responses (32%) were reported. One of the principal advantages of this class of agents is its very low toxicity (317). Targeted Therapies Knowledge of molecular pathways within normal and malignant cells is leading to the development of cancer treatment agents with specific molecular targets. Bevacizumab is the first targeted agent to show significant single agent activity in ovarian cancer. A study of low-dose metronomic chemotherapy with 50 mg of cyclophosphamide daily and bevacizumab 10 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks showed significant activity in a study of 70 patients with recurrent ovarian cancer (320). The side effects of bevacizumab are well recognized and include hypertension, fatigue, proteinuria, gastrointestinal perforation or fistula, and uncommonly, vascular thrombosis and central nervous system ischemia, pulmonary hypertension, and bleeding and wound healing complications. The most common side effects are hypertension that is grade 3 in 7% of patients and is usually treatable. The most concerning side effect is bowel perforation and the study by Cannistra et al. It was suggested that the bowel perforation complication could be avoided by carefully screening patients. Their study included 25 patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer who were heavily pretreated, and they observed a response rate of 28% and no bowel perforations or any other grade 3 or 4 toxicities were reported. This highlights the importance of patient selection and suggests that increased experience with these agents will result in less toxicity. There are other oral agents that target angiogenesis through tyrosine kinase inhibition that are in clinical trial (323). Radiation Therapy Whole-abdominal radiation therapy given as a treatment for recurrent or persistent disease is associated with a high morbidity and is not used. The principal problem associated with this approach is the development of acute and chronic intestinal morbidity. As many as 30% of patients treated with this approach develop intestinal obstruction, which necessitated exploratory surgery with potential morbidity (324). The intestinal blockage can be corrected in most patients whose obstruction appears at initial diagnosis. The decision to perform an exploratory procedure to ease intestinal obstruction in patients with recurrent disease is more difficult. In those patients with a longer projected lifespan, features predicting a reasonable likelihood of correcting the obstruction include young age, good nutritional status, and the absence of rapidly accumulating ascites (326). For most patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and intestinal obstruction, initial management should include proper radiographic documentation of the obstruction, hydration, correction of any electrolyte disturbances, parenteral alimentation, and intestinal intubation. For some patients, the obstruction may be alleviated by this conservative approach. A preoperative upper gastrointestinal radiographic series and a barium enema will define possible sites of obstruction. If exploratory surgery is deemed appropriate, the type of operation to be performed will depend on the site and the number of obstructions. Multiple sites of obstruction are not uncommon in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. If multiple obstructions are present, resection of several segments of intestine is usually not indicated, and intestinal bypass and/or colostomy should be performed. A gastrostomy may be useful in this circumstance, and this can usually be placed percutaneously (336, 339). The need for multiple reanastomoses and prior radiation therapy increase the morbidity, which consists primarily of sepsis and enterocutaneous fistulae. Survival the prognosis for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer is related to several clinical variables. Including patients at all stages, patients younger than 50 years of age have a 5-year survival rate of about 40%, compared with about 15% for patients older than 50 years. In Twenty-sixth annual report of the results of treatment of gynaecological cancer. Survival of patients with borderline tumors is excellent, with stage I lesions having a 98% 15-year survival (30). When all stages of borderline tumors are included, the 5-year survival rate is about 86% to 90%. Nonepithelial Ovarian Cancers Compared with epithelial ovarian cancers, other malignant tumors of the ovary are uncommon. Nonepithelial malignancies of the ovary account for about 10% of all ovarian cancers (2, 3, 342). Germ Cell Malignancies Germ cell tumors are derived from the primordial germ cells of the ovary. Their incidence is about one-tenth the incidence of malignant germ cell tumors of the testis, so most of the advances in the management of these tumors are extrapolations from experience with the corresponding testicular tumors. Although malignant germ cell tumors can arise in extragonadal sites such as the mediastinum and the retroperitoneum, most germ cell tumors arise in the gonad from undifferentiated germ cells.

Curriculum differentiation involves processes of modifying arthritis in neck causes buy 16 mg medrol visa, changing arthritis pain relief liquid order medrol 16 mg line, adapting arthritis xiphoid process buy cheap medrol on line, extending arthritis in hips for dogs cheap 4mg medrol mastercard, and varying teaching methodologies arthritis in fingers and hand buy medrol 4mg amex, teaching and assessment strategies and the content of the curriculum (Department of Education arthritis diet reviews order on line medrol, 2011). Moreover, curriculum differentiation enables all learners in an inclusive classroom to learn according to their individual needs (Gordon, 2013). Multi level teaching considers the different types of learner needs within a classroom and provides learners with appropriate curricular and environmental modification to enable them to learn in ways that are appropriate to their learning style and academic goals (Gordon, 2013). In the sub-section that follows, I present different ways in which teaching and learning could be adapted to meet the needs of learners with dyslexia. When assigning a task, the teacher will divide learners into separate groups according to their different levels. The teacher will end the lesson with the whole class together in the application stage of the lesson (Department of Education, 2011; Engelbrecht, 2013a). Pavey (2007) suggests that the tasks ought to be both relevant and manageable for 34 learners with dyslexia as these learners need ways of displaying their knowledge. Curriculum differentiation and adaptation can be done at the level of content through differentiation in learning materials, the level of teaching methodologies through differentiation in methods of lesson presentation and lesson organisation, and the level of learning environment through differentiated assessments (Department of Education, 2011). Differentiation in learning materials Learners are provided with a wide range of learning materials that cater for different abilities, interests and learning styles. Teachers need to be aware that learning materials might need to be adapted for learners with learning difficulties. For example, a learner with poor vision or a learner experiencing reading difficulties might need a larger print to be able to read easily (Department of Education, 2011). Learners with dyslexia access information differently, and it is more likely that the learner will benefit if the information is presented in a variety of styles. Textbooks, lecturing, and notes could therefore be supplemented or replaced by music, movement, and visual elements such as pictures, diagrams, and charts (Gordon, 2013). Differentiation in methods of presentation Teachers can modify the format in which tasks are presented, for example, the complexity of graphs, diagrams, illustrations, and cartoons. Pictures or diagrams could be replaced or supplemented by written descriptions and explanations. Also, the amount of information could be reduced, and unnecessary pictures of diagrams could be removed (Department of Education, 2011). Differentiation in lesson organisation Teachers need to differentiate the way in which activities are planned in a lesson to ensure maximum involvement and participation of learners in the lesson. Building a collaborative network of support for teachers is imperative to successful curriculum differentiation. Through collaboration, teachers can learn from one another, support the tasks of one another, develop learning materials together, and serve as a resource to one another (Department of Education, 2011). Since inclusive classrooms become increasingly prevalent, it is anticipated that more and more teachers will need to meet the needs of learners with dyslexia. As already mentioned, dyslexia is a chronic, persistent specific learning difficulty and is neither a developmental lag nor outgrown (Shaywitz et al. According to the National Reading Panel (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000), aspects of teaching reading include decoding, fluency, and comprehension. The report of the National Reading Panel identified the use of explicit instruction of letter-sound relationships to teach decoding. Fluency was most effectively taught through guided, repeated oral reading, and comprehension was found to be best taught through both direct and indirect vocabulary instruction. Text comprehension was taught most effectively through the use of cooperative learning, monitoring, questions 36 answering, analysis, and summarisation (Marchand-Martella, Martella, Modderman, Petersen, & Pan, 2013). The implication concerning dyslexia is that reading problems must be recognised early and addressed (Shaywitz et al. Furthermore, metacognitive strategies assisting with word recognition and meaning of text reduce the base rates of at-risk learners to below 5% (Shaywitz et al. However, it appears that systematic, structured programmes can significantly improve core reading skills in the weakest readers at these ages (Allen, 2010). Normally these programmes include activities such as word recognition skills, word attack skills (the ability to make sense of an unknown word), word identification and fluency skills (Thompson, 2014). It is equally important that teachers are properly trained in phonological instruction and that this instruction is provided in a small group or one-to-one setting to better the outcomes for learner reading achievement (Allen, 2010; Williams, 2012). Investigations using remedial interventions that begin after the second grade indicate that it is more challenging to bring learners up to the expected grade levels once they fall behind. Although promising, interventions have yet to close the gap in the ability in learners experiencing dyslexia to read fluently because these learners often remain accurate but slow readers (Shaywitz et al. It is, however, imperative that primary school teachers should understand that 37 the longer it takes to identify learners with dyslexia, the more difficult it will be to teach them to read proficiently (Allen, 2010). Intervention does not only include specific language-based skill activities but also includes concessions, accommodations and modifications for the learner with dyslexia (International Dyslexia Association, 2012; Thompson, 2014). High-quality intervention (Farrell, 2012; Shaywitz, 2003; Snowling, 2013), strong oral language skills, ability to maintain attention as well as good family support are protective factors that lead to better outcomes for these learners (Bornman & Rose, 2010; Williams & Lynch, 2010). Therefore, teachers should be able to identify the specific barriers to learning which impede learners from developing their potential (Lessing, 2010). Teachers do not diagnose dyslexia because of its medical nature; they will rather label the learner as having a learning difficulty in reading (Williams, 2012). In the sub-section that follows, I present a few teaching and assessment strategies which could enable teachers to teach, support, and accommodate learners with dyslexia in an inclusive classroom. In general, there are three types of accommodations: (a) those that provide information through an auditory mode, by-passing reading difficulty, (b) those that provide assistive technologies, and (c) those that provide additional time so that learners with diffluent reading abilities can demonstrate their knowledge. Gordon (2013) and Jusufi (2014) hold the view that if teachers are aware of dyslexia and its manifestations, they might have better approaches towards learners with dyslexia. When teachers are knowledgeable and apply the appropriate strategies, they facilitate the academic and social success of learners with dyslexia as well as non-dyslexic learners who are also experiencing learning difficulties. With a more extensive knowledge of dyslexia, teachers can help learners with dyslexia in many ways without thinking that these learners only need professional intervention (Jusufi, 2014). Thompson (2014) supports the view of Gordon (2013) since most learners with dyslexia do not have access to personal, individualised and one-to-one intervention as they are not removed from the class setting in ordinary schools. It is, therefore, imperative that learners with dyslexia are provided with extra support and assistance especially in the language classroom (Erkan, K z laslan, & Dogru, 2012). Thus, when teachers understand the nature and characteristics of dyslexia, they are better able to address the needs of learners with dyslexia and assist them to learn optimally (Bornman & Rose, 2010; Williams & Lynch, 2010). Referring to Appendix A2: Addendum to Chapter 2: Literature Review, I present a summary of the areas of difficulty (Bell et al. The processes that may interfere with learning are complex, and sensitive teachers should notice when and in which tasks learners experience difficulties (Pavey, 2007). It is recommended that marking should be limited to a portion of the writing rather than the whole, and some teachers will avoid red ink as it represents connotations of failure (Pavey, 2007). Another strategy is to put a tick on a line where no errors are made and using a dot alongside the margin to indicate an error. Pavey (2007) also suggests that work should be marked in relation to the learning objective, which has been explained to the learners beforehand so that they understand what is being marked and why. Formal assessments and tests Learners with dyslexia may require assistance with test instructions. A variety of question types should be utilised, although lengthy test sections should be avoided. For learners with dyslexia, the testing time needs to be lengthened or the number of test items should be reduced. It is more comfortable for learners with dyslexia to write directly on the test, rather than using an answer sheet. The testing environment should be as stress-free as possible, and it might be necessary to allow the learner to complete the test in another room. Extra time and explicit instructions could ease anxiety and alleviate apprehension. Turning now to classroom management and classroom management strategies, I discuss the central role of teachers in skilfully managing their classrooms because the teaching and supporting of learners with dyslexia depends on the way in which teachers manage their classrooms. Classroom environments refer not only to the physical conditions within a classroom but also to the psychosocial climate that has a reciprocal influence on those physical learning conditions (Engelbrecht, 2013c). Thus, classroom management can be defined as everything that is under the direct control of the teacher (Plevin, 2013) which includes lesson planning, time management and discipline (Kendall, 2008). The holistic approach views learners as individuals with physical, cognitive, social, emotional and spiritual needs. For teachers to maintain a whole-child approach, they need a continuous approach that focuses on the full range of learner needs. Rather than being on the lookout for problems in the classroom, they look for solutions. They communicate that they are there to help learners rather than find fault with them. When problems do occur, the teacher seizes control of the situation and responds in a manner that conveys care, fairness and consideration (Plevin, n. Therefore, skilled classroom management can support or impede the learning process for learners (Bishop et al. As learners spend most of their time in the classroom and other school settings, they are expected to follow instructions and to participate in organised learning activities in a socially appropriate manner (Kendall, 2008). In her study, Kendall (2008) found that teachers have to change strategies all the time to successfully manage classroom discipline. Considering the above, the present study investigated the way in which Intermediate Phase teachers had managed their teaching styles and classroom management strategies to support the learner with dyslexia. To create a positive, learning-friendly classroom environment, Plevin (2008) offers a variety of possible scenarios and strategies. With reference to the Addendum to Chapter 2: Literature Review in Appendix A2, he suggests possible classroom strategies which teachers could apply to control the learning environment in their classrooms. As was pointed out in the introduction to this chapter, the next section is concerned with inclusive education and the possible challenges experienced by teachers in teaching and supporting learners with dyslexia. This implies that education for all children from ages seven to 15 years, including learners who are experiencing barriers to learning, is compulsory as mandated by the South African Schools Act Number 84 (Department of Basic Education, 1996) and the Education White Paper Six, Special Needs Education: Building an inclusive education and training system (Department of Education, 2001). Since classified as a learning impairment, dyslexia is accommodated within this legislation and policy. Inclusion requires changing the culture and organisation of the school in order to create sustainable systems which develop and support flexible approaches to learning (Swart & Pettipher, 2012). The challenges, however, do not lie in the design of policies around special needs but rather in the implementation thereof (Thompson, 2014). Cardona (2009) points out that successful implementation of inclusion policies depends largely on teachers having the knowledge, skills, and competency to make it work. Thus, the transformation in South African education practices presents teachers with new opportunities and challenges regarding the implementation of these policies (Bornman & Donohue, 2013). A few of the elements of educational change (Swart & Pettipher, 2012) and the associated challenges (Stofile & Green, 2007) thereof are discussed below. School principals have a responsibility to set the tone of the school and help the school to become and maintain a supportive and caring community (ibid. Furthermore, schools should organise courses for teachers to inform them about learning difficulties and to enable them to teach learners with dyslexia in a supportive teaching and learning environment (ibid. Similarly, Hodkinson (2006) suggests that barriers to inclusive education are located within the locus of individual schools. It has been reported that inclusion is being delayed because educational institutions are not able to include all learners due to a lack of knowledge, vision, resources, and morality (Hodkinson, 2006).

It is a fascia-lined space located inferiorly between the perineal skin and the pelvic diaphragm superiorly; it communicates with the contralateral ischiorectal fossa over the anococcygeal ligament arthritis in fingers pain relief best buy medrol. Superiorly arthritis lumps purchase medrol 4 mg visa, its apex is at the origin of the levator ani muscle from the obturator fascia rheumatoid arthritis thyroid best purchase for medrol. It is bound medially by the levator ani and the external sphincter with their fascial covering arthritis in neck physical therapy order medrol with a visa, laterally by the obturator internus muscle with its fascia arthritis in the knee home remedies order discount medrol on line, posteriorly by the sacrotuberous ligament and the lower border of the gluteus maximus muscle arthritis in back hereditary cheap 4mg medrol mastercard, and anteriorly by the base of the urogenital diaphragm. An ischiorectal abscess should be drained without delay, or it will extend into the anal canal. The cavity is filled with fat that cushions the anal canal and is traversed by many fibrous bands, vessels, and nerves, including the pudendal and the inferior rectal nerves. The perforating branch of S2 and S3 and the perineal branch of S4 also run through this space. The pudendal (Alcock) canal is a tunnel formed by a splitting of the inferior portion of the obturator fascia running anteromedially from the ischial spine to the posterior edge of the urogenital diaphragm. It contains the pudendal artery, vein, and nerve in their traverse from the pelvic cavity to the perineum. Blood Supply the blood supply to the anal triangle is from the inferior rectal (hemorrhoidal) artery and vein. Innervation the innervation to the anal triangle is from the perineal branch of the fourth sacral nerve and the inferior rectal (hemorrhoidal) nerve. Retroperitoneum and Retroperitoneal Spaces the subperitoneal area of the true pelvis is partitioned into potential spaces by the various organs and their respective fascial coverings and by the selective thickenings of the endopelvic fascia into ligaments and septa (Fig. It is imperative that surgeons operating in the pelvis be familiar with these spaces, as discussed below. The Mackenrodt ligament extends from the lateral cervix to the lateral abdominal pelvic wall. The vesicouterine ligament originating from the anterior edge of the Mackenrodt ligament leads to the covering of the bladder on the posterior side. The sagittal rectum column spreads both to the connective tissue of the rectum and the sacral vertebrae closely nestled against the back of the Mackenrodt ligament and lateral pelvic wall. Between the firm connective tissue bundles is loose connective tissue (paraspaces). It is separated from the paravesical space by the ascending bladder septum (bladder pillars). Upon entering the prevesical space, the pubourethral ligaments may be seen inserting into the posterior aspect of the symphysis pubis as a thickened prolongation of the arcus tendineus fascia. With combined abdominal and vaginal bladder neck suspensory procedures, the point of entry is usually the Retzius space between the arcus tendineus and the pubourethral ligaments. Paravesical Spaces the paravesical spaces are fat filled and limited by the fascia of the obturator internus muscle and the pelvic diaphragm laterally, the bladder pillar medially, the endopelvic fascia inferiorly, the lateral umbilical ligament superiorly, the cardinal ligament posteriorly, and the pubic bone anteriorly. Vesicovaginal Space the vesicovaginal space is separated from the Retzius space by the endopelvic fascia. This space is limited anteriorly by the bladder wall (from the proximal urethra to the upper vagina), posteriorly by the anterior vaginal wall, and laterally by the bladder septa (selective thickenings of the endopelvic fascia inserting laterally into the arcus tendineus). A tear in these fascial investments and thickenings medially, transversely, or laterally allows herniation and development of a cystocele. Rectovaginal Space the rectovaginal space extends between the vagina and the rectum from the superior border of the perineal body to the underside of the rectouterine Douglas pouch. It is bound anteriorly by the rectovaginal septum (firmly adherent to the posterior aspect of the vagina), posteriorly by the anterior rectal wall, and laterally by the descending rectal septa separating the rectovaginal space from the pararectal space on each side. The rectovaginal septum represents a firm membranous transverse septum dividing the pelvis into rectal and urogenital compartments, allowing the independent function of the vagina and rectum and providing support for the rectum. It is fixed laterally to the pelvic sidewall by rectovaginal fascia (part of the endopelvic fascia) along a line extending from the posterior fourchette to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, midway between the pubis and the ischial spine (42). An anterior rectocele often results from a defective septum or an avulsion of the septum from the perineal body. Reconstruction of the perineum is critical for the restoration of this important compartmental separation and for the support of the anterior vaginal wall (43). Pararectal Space the pararectal space is bound laterally by the levator ani, medially by the rectal pillars, and posteriorly above the ischial spine by the anterolateral aspect of the sacrum. It is separated from the retrorectal space by the posterior extension of the descending rectal septa. Retrorectal Space the retrorectal space is limited by the rectum anteriorly and the anterior aspect of the sacrum posteriorly. It communicates with the pararectal spaces laterally above the uterosacral ligaments and extends superiorly into the presacral space. Presacral Space the presacral space is the superior extension of the retrorectal space and is limited by the deep parietal peritoneum anteriorly and the anterior aspect of the sacrum posteriorly. It harbors the middle sacral vessels and the hypogastric plexi between the bifurcation of the aorta invested by loose areolar tissue. Presacral neurectomy requires familiarity with and working knowledge of this space. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy involves dissection in the presacral space down to the anterior longitudinal ligament, which is the point of fixation for the tail of the Y-shaped mesh graft. The surgical space is bound superiorly by the bifurcation of the great vessels and laterally by the ureter on the right and the mesentery of the sigmoid colon and the left common iliac vein on the left. The left iliac vein lies medial to the left iliac artery bounding this space and is more prone to injury during laparoscopic entry or presacral dissection. Peritoneal Cavity the female pelvic organs lie at the bottom of the abdominopelvic cavity covered superiorly and posteriorly by the small and large bowel. Anteriorly, the uterine wall is in contact with the posterosuperior aspect of the bladder. The uterus is held in position by the following structures: the round ligaments coursing inferolaterally toward the internal inguinal ring the uterosacral ligaments, which provide support to the cervix and upper vagina and interdigitate with fibers from the cardinal ligament near the cervix the cardinal ligaments, which provide support to the cervix and upper vagina and contribute to the support of the bladder Anteriorly, the uterus is separated from the bladder by the vesicouterine pouch and from the rectum posteriorly by the rectouterine pouch or Douglas cul-de sac. Laterally, the bilateral broad ligaments carry the neurovascular pedicles and their respective fascial coverings, attaching the uterus to the lateral pelvic sidewall. The broad ligament is in contact inferiorly with the paravesical space, the obturator fossa, and the pelvic extension of the iliac fossa, to which it provides a peritoneal covering, and with the uterosacral ligament. Ureter In its pelvic path in the retroperitoneum, several relationships are of significance and identify areas of greatest vulnerability to injury of the ureter (Fig. The ovarian vessels cross over the ureter as it approaches the pelvic brim and lie in lateral proximity to the ureter as it enters the pelvis. As the ureter descends into the pelvis, it runs within the broad ligament just lateral to the uterosacral ligament, separating the uterosacral ligament from the mesosalpinx, mesovarium, and ovarian fossa. At about the level of the ischial spine, the ureter crosses under the uterine artery in its course through the cardinal ligament; the ureter divides this area into the supraureteric parametrium surrounding the uterine vessels and the infraureteric paracervix molded around the vaginal vessels and extending posteriorly into the uterosacral ligament. In this location, the ureter lies 2 to 3 cm lateral to the cervix and in proximity to the insertion of the uterosacral ligament at the cervix. This proximity warrants caution when using the uterosacral ligament for vaginal vault suspension (44, 45). The ureter then turns medially to cross the anterior upper vagina as it traverses the bladder wall. About 75% of all iatrogenic injuries to the ureter result from gynecologic procedures, most commonly abdominal hysterectomy (46). Distortions of pelvic anatomy, including adnexal masses, endometriosis, other pelvic adhesive disease, or fibroids, may increase susceptibility to injury by displacement or alteration of usual anatomy. Careful identification of the course of the ureter before securing the infundibulopelvic ligament and uterine artery is the best protection against ureteric injury during hysterectomy or adnexectomy. Even with severe intraperitoneal disease, the ureter can always be identified using a retroperitoneal approach and noting fundamental landmarks and relationships. Pelvic Floor the pelvic floor includes all of the structures closing the pelvic outlet from the skin inferiorly to the peritoneum superiorly. It is commonly divided by the pelvic diaphragm into a pelvic and a perineal portion (47). The pelvic diaphragm is spread transversely in a hammocklike fashion across the true pelvis, with a central hiatus for the urethra, vagina, and rectum. Anatomically and physiologically, the pelvic diaphragm can be divided into two components: the internal and external components. The external component originates from the arcus tendineus, extending from the pubic bone to the ischial spine. It gives rise to fibers of differing directions, including the pubococcygeus, the iliococcygeus, and the coccygeus. The internal component originates from the pubic bone above and medial to the origin of the pubococcygeus and is smaller but thicker and stronger (47). Its fibers run in a sagittal direction and are divided into the following two portions: Pubovaginalis fibers run in a perpendicular direction to the urethra, crossing the lateral vaginal wall at the junction of its lower one-third and upper two-thirds to insert into the perineal body. The intervening anterior interlevator space is covered by the urogenital diaphragm. Puborectalis superior fibers sling around the rectum to the symphysis pubis; its inferior fibers insert into the lateral rectal wall between the internal and external sphincter. The pelvic diaphragm is covered superiorly by fascia, which includes a parietal and a visceral component and is a continuation of the transversalis fascia (Fig. The parietal fascia has areas of thickening (ligaments, septae) that provide reinforcement and fixation for the pelvic floor. The visceral (endopelvic) fascia extends medially to invest the pelvic viscera, resulting in a fascial covering to the bladder, vagina, uterus, and rectum. It becomes attenuated where the peritoneal covering is well defined and continues laterally with the pelvic cellular tissue and neurovascular pedicles. Musculofascial elements (the hypogastric sheath) extend along the vessels originating from the internal iliac artery. Following these vessels to their respective organs, the hypogastric sheath extends perivascular investments that contribute to the formation of the endopelvic fascia so critical for the support of the pelvic organs. Thus, the parietal fascia anchors the visceral fascia, which defines the relationship of the various viscera and provides them with significant fixation (uterosacral and cardinal ligaments), septation (vesicovaginal and rectovaginal), and definition of pelvic spaces (prevesical, vesicovaginal, rectovaginal, paravesical, pararectal, and retrorectal). For its support, the pelvic floor relies on the complementary role of the pelvic diaphragm and its fascia resting on the perineal fibromuscular complex. It is composed of the perineal membrane (urogenital diaphragm) anteriorly and the perineal body joined to the anococcygeal raphe by the external anal sphincter posteriorly. This double-layered arrangement, when intact, provides optimal support for the pelvic organs and counterbalances the forces pushing them downward with gravity and with any increase in intra-abdominal pressure (Fig. Histologic studies reveal that the linings of the levator ani, piriformis, and obturator internus are genuine examples of pelvic fascia. There are no discrete capsules of fascia that separate the bladder and vagina from each other. The endopelvic fascia is a sheet of fibroareolar tissue following the blood supply to the visceral organs and acts as a retroperitoneal mesentery. The endopelvic or pubocervical fascia attaches the cervix and vagina to the lateral pelvic sidewall. It is composed of two parts: the parametrium, which is that part connected to the uterus. The parametrium and cardinal ligaments continue to the vaginal introitus and fuse directly to the supporting tissues associated with the vagina. The uterosacral ligaments are the posterior components of the cardinal ligaments, extending from the cervix and upper vagina to the lateral sacrum. Lateral pelvic support is provided by linear condensations of obturator and levator ani fascia termed the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis and the arcus tendineus levator ani, respectively. The arcus tendineus levator ani serves as a point of attachment for the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus muscles and lies on the fascia of the obturator internus muscle. The arcus tendineus fascia pelvis runs from the anterior pubis to the ischial spine as it joins with the arcus tendineus levator ani. Obturator Space the obturator membrane is a fibrous sheath that spans the obturator foramen through which the obturator neurovascular bundle penetrates via the obturator canal. The obturator internus muscle lies on the superior (intrapelvic) side of the obturator membrane. The origin of the obturator internus is on the inferior margin of the superior pubic ramus and the pelvic surface of the obturator membrane. Its tendon passes through the lesser sciatic foramen to insert onto the greater trochanter of the femur to laterally rotate the thigh. The obturator artery and vein originate as branches of the internal iliac vessels. As they emerge from the cranial side of the obturator membrane via the obturator canal and enter the obturator space, they divide into many small branches, supplying blood to the muscles of the adductor compartment of the thigh. Cadaver work contradicted previous reports that the obturator vessels bifurcate into medial and lateral branches (48). Rather, the vessels are predominantly small (< 5 mm in diameter) and splinter into variable courses. The muscles of the medial thigh and adductor compartment are (from superficial to deep) the gracilis, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, obturator externus, and obturator internus. In contrast to the vessels, the obturator nerve emerges from the obturator membrane and bifurcates into anterior and posterior divisions, traveling distally down the thigh to supply the muscles of the adductor compartment. With the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position, the nerves and vessels follow the thigh and course laterally away from the ischiopubic ramus.

Discount 16 mg medrol amex. Bcaa powder works great on dogs with arthritis.

References

- Balderramo DC, Pellise M, Colomo L, et al. Diagnosis of pleural malignant mesothelioma by EUS-guided FNA (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(6):1191-1192, dicussion 1192-1193.

- Ngan Kee WD. Laryngeal mask airway for radiotherapy in the prone position. Anaesthesia. 1992;47:446-7.

- Moriyama N, Akiyama K, Murata S, et al: KMD-3213, a novel alpha1Aadrenoceptor antagonist, potently inhibits the functional alpha1-adrenoceptor in human prostate, Eur J Pharmacol 331(1):39n42, 1997.

- Robbins WA, Meistrich ML, Moore D, et al. Chemotherapy induces transient sex chromosomal and autosomal aneuploidy in human sperm. Nat Genet 1997;16(1):74-78.

- Saint-Blancard P, Harket A, Defuentes G, et al. Primary pleural lymphoma: a late complication of pleural decortication for tuberculosis: two cases in western countries. Rev Pneumol Clin 2007;63:277-81 572.

- Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). NIH Publication No. 02-5215.

- Gielen V, Johnston SL, Edwards MR. Azithromycin induces anti-viral responses in bronchial epithelial cells. Eur Respir J 2010; 36: 646-654.