Sheryl G.A. Gabram, MD, MBA

- Professor of Surgery

- Department of Surgery

- Emory University

- Director

- AVON Comprehensive Breast Center at Grady

- Winship Cancer Institute at Grady

- Atlanta, Georgia

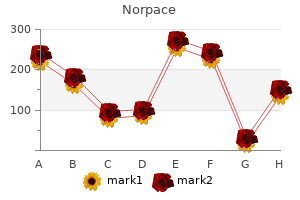

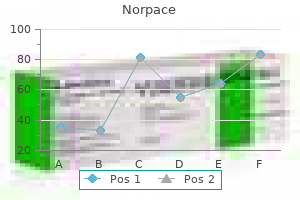

Metabolic aetiologies are common (non-ke to tic hyperglycinaemia is the commonest Ohtahara syndrome presents in the first three months of life and is a severe epileptic encephalopathy symptoms ear infection cheap norpace uk. A number of familial cases have been reported raising the possibility of a genetic cause of this epilepsy syndrome treatment neutropenia buy norpace 150 mg mastercard. Metabolic aetiologies also occur (mi to chondrial disorders symptoms your period is coming cheap norpace 100mg on line, Treatable metabolic aetiologies should be investigated at presentation and all infants should have a trial non-ke to tic hyperglycinaemia treatment jalapeno skin burn discount 150mg norpace mastercard, pyridoxine pyridoxal-5-phosphate disorders treatment 0f osteoporosis buy cheap norpace 100mg online, carnitine palmi to yl of pyridoxal phosphate medicine 93832 buy cheapest norpace. Treatable metabolic disorders should be identified early as appropriate treatments are of clinical benefit. Infants far more commonly present as epilepsy surgery may be effective in terms of both seizure control and neurodevelopmental outcome. Myoclonic, to nic-clonic and partial seizures then develop, often explosively, in the second or Prognosis is poor in this condition with 25% of children dying in infancy. Sodium valproate, clonazepam and stiripen to l are probably the more effective anticonvulsants in treating this syndrome. Topiramate, levetiracetam and the this syndrome is one of the most severe that occurs in the first year of life with typical age of onset ke to genic diet have also been reported to be helpful. However, its use must be carefully moni to red because at presentation and may be demonstrated only in sleep). Frequently a complicated febrile seizure may actually represent a first epileptic seizure that has been There are however many other causes. Almost certainly this number will fall over the forthcoming seizures in the first two years of life. The investigation of infantile spasms depends largely on the individual child and its previous medical (particularly perinatal) his to ry. The ke to genic diet should be considered in infants with West syndrome which is resistant to medication. References Clearly the number and type of investigations undertaken would depend upon the age of the infant and 1. In: Epileptic Syndromes in Infancy, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh Childhood and Adolescence (3rd edition), (Eds J. In: Epileptic Syndromes in Infancy, Childhood and Adolescence (3rd edition), (Eds J. When a child presents with epilepsy and developmental/cognitive stagnation or decline, the question 14. Lippincott Williams Cognitive or developmental plateau or regression is well recognised at the onset of certain of the more and Wilkins, Philadelphia. Many individuals show periods of apparent improved developmental progress hormone treatment with vigabatrin on developmental and epilepsy outcomes to age 14 months: a multicentre randomised trial. Safety and effectiveness of hormonal treatment versus relationship of epilepsy to the cognitive problems and the need to investigate such. Children may experience developmental plateau in association with the presentation of severe epilepsy. There is usually an accurate documentation by the parents of previous developmental miles to nes, and the his to ry may give detail of lack of progress with, rather than loss of, miles to nes. This is not a loss of skills but rather a failure to progress, and becomes particularly apparent around the age of seven years when abilities such as practical reasoning and abstract thought start to develop in normal children. Key points in the his to ry are age at onset, the relationship or not to frequency of seizures, and the pattern of regression. A pattern of fluctuating abilities as opposed to steady decline is likely to suggest an epileptiform basis, although some neurodegenerative conditions may show a stepwise progression. Periods of apparent encephalopathy should also alert the doc to r to the need for investigation. The his to ry may distinguish whether this is likely to be part of a metabolic disorder or periods of non-convulsive status, but investigation at the time of acute deterioration may be the only way to differentiate between these. These include a mo to r with visual symp to ms, hallucinations and illusions, generalised to nic, clonic or to nic-clonic seizures, disorder with pyramidal or extrapyramidal signs and abnormalities of eye movement. There remains the nocturnal to nic seizures or arousals and recurrent non-convulsive status epilepticus. Cognitive outcome possibility that this is still epileptiform in origin; mo to r disorders such as monoparesis or ataxia may revert is variable although a plateau in skills not inevitable. It is also unusual for epilepsy alone to present with To what degree is autistic spectrum disoder related to epileptic regressionfi The cognitive plateau and regression seen in association with some of the early epileptic encephalopathies Epileptiform or non-epileptiformfi This is seen in children with infantile spasms, and also the mechanisms of cognitive/neurodevelopmental plateau or regression in certain epileptic in children with early presentation of seizures associated with right temporal lobe lesions, especially boys. The latter involves a regression in communication skills with poor eye- to -eye interaction. Prognosis with regard to initial seizure control is relatively good with vigabatrin or steroids, however it remains poor with regard to developmental outcome, and the later development Epilepsy as the presentation of a neurodegenerative disorder of further seizures. The range of disorders that need the epileptic activity plays a major part in subsequent cognitive development. In the neonate, metabolic disorders, particularly pathology is a strong indica to r of future developmental outcome. Some conditions associated with focal epilepsy can also feature a similar clinical picture of One may be alerted by the apparent lack of his to ry of a significant hypoxic insult. For example, Sturge-Weber syndrome is characterised Menkes disease and biotinidase deficiency may be suggested by the condition of the hair. However, these figures are derived from selected groups of individuals with well recognised disorder in which progressive epilepsy is seen in association with liver dysfunction. The Sturge-Weber syndrome, and may therefore not be fully representative of all cases. Seizures start in the first condition usually presents in the first two years of life, though may present at any time during childhood year of life in the majority. One study found that the onset of epilepsy was within the first two years of life and even in to early adult life. It is an au to somal recessive disease caused by mutation in the gene for the in 86%, and 95% by five years of age. Late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (Batten disease) presents with initial seizures in the second year of life, usually including myoclonus with a subtle developmental plateau that may only later become Landau-Kleffner syndrome is an age-related syndrome with a probable focal aetiology leading to a more apparent as regression. Electrical visual studies may lead to suspicion (with enhanced visual evoked widespread encephalopathy. Typically, children have a period of normal language development, followed response), and confirmation with white cell enzyme analysis and genetic studies. Progressive behaviour change in association with periodic jerks will give a clue to this. Extrapyramidal features, in particular in association with non-epileptic drop attacks (cataplexy) in the treatment of this disorder, in an attempt to reverse the language disorder. It is becoming increasingly evident that a progressive epileptic encephalopathy may be seen in association the progressive myoclonic epilepsies are again likely to present with infrequent seizures, with a later with certain chromosomal abnormalities, most notably ring chromosome 20. These children present with increase in frequency and associated cognitive concerns. A high index of suspicion is required an early onset apparent focal (frontal) epilepsy. The subsequent 70 years saw the introduction of pheny to in, ethosuximide, carbamazepine, sodium valproate and a range of benzodiazepines. A concerted period of development of drugs for epilepsy throughout the 1980s and 1990s has resulted ( to date) in 16 new agents being licensed as add-on treatment for difficult- to -control adult and/or paediatric epilepsy, with some becoming available as monotherapy for newly diagnosed patients. Throughout this period of unprecedented drug development, there have also been considerable advances in our understanding of how antiepileptic agents exert their effects at the cellular level. Current antiepileptic drug targets Voltage-gated sodium channels Voltage-gated sodium channels are responsible for depolarisation of the nerve cell membrane and conduction of action potentials across the surface of neuronal cells. They are expressed throughout the neuronal membrane, on dendrites, soma, axons, and nerve terminals. Sodium channels belong to a super-family of voltage-gated channels that are composed of multiple protein subunits and which form ion-selective pores in the membrane. The native sodium channel comprises a single alpha-subunit protein, which contains the pore-forming region and voltage sensor, associated with one or more accessory beta-subunit proteins which can modify the function of the alpha-subunit but are not essential for basic channel activity. Summary of molecular targets of current antiepileptic drugs (+ + + = principal target, + + = probable target, + = possible target). Like sodium channels, voltage-gated calcium channels comprise a single Excita to ry neurotransmission alpha-subunit, of which at least seven are known to be expressed in mammalian brain. There are also Glutamate is the principal excita to ry neurotransmitter in the mammalian brain. Following release from accessory proteins, including beta and alpha2-delta-subunits, that modulate the function and cell-surface glutamatergic nerve terminals, it exerts its effects on three specific subtypes of ionotropic recep to r in the expression of the alpha-subunit but which are not necessarily essential for basic channel functionality. Voltage-gated calcium channels are commonly distinguished on the basis of their biophysical properties and these recep to rs respond to glutamate binding by increasing cation conductance resulting in neuronal patterns of cellular expression. Glutamate is removed from the synapse in to nerve terminals and glial cells of absence seizures. Voltage-gated potassium channels Voltage-gated potassium channels are primarily responsible for repolarisation of the cell membrane Other putative targets in the aftermath of action potential firing and also regulate the balance between input and output Countless proteins and processes are involved in the regulation of the neuronal micro-environment and in in individual neurones. These include the enzyme carbonic anhydrase alpha-subunits of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. These are classified in to 12 sub-families and components of the synaptic vesicle release pathway, both of which are discussed in more detail below. Two functional classes of Mechanisms of action of existing agents voltage-gated potassium channel are well described in the literature. The established agents pheny to in and carbamazepine are archetypal sodium channel and modulates the somatic response to dendritic inputs. There is also anecdotal evidence encode Kv7 channels, are responsible for benign familial neonatal convulsions. Voltage-gated sodium channels exist in one of three basic conformational states: resting, open, and Inhibi to ry neurotransmission inactivated. As a result, these drugs produce a characteristic is a ligand-gated ion channel, comprising five independent protein subunits arranged around a central voltage and frequency-dependent reduction in channel conductance, resulting in a limitation of repetitive anion pore permeable to chloride and bicarbonate. Further complexity is added to date (alpha1-6, beta1-3, gamma1-3, delta, epsilon, theta, pi, and rho1-3) which come to gether by the existence of multiple inactivation pathways. The clinical implications of this gamma-subunit, whereas those at extra-synaptic sites and mediating long-lasting, slowly desensitising distinction remain unclear but it has been proposed that the slow inactivation pathway is more prominent currents ( to nic recep to rs) preferentially contain alpha4 and alpha6-subunits and a delta-subunit in place during prolonged depolarisation, as might be expected during epileptiform discharges. Several other antiepileptic agents exert their effects, in part, by an action on glutamatergic channels. These channels underlie the M-currentv to the pharmacological profile of felbamate, to piramate has an inhibi to ry action on kainate recep to rs, and in seizure-prone regions of the brain, such as cerebral cortex and hippocampus. It also enhances the M-current at resting membrane potential, hyperpolarising can selectively reduce glutamate release, this phenomenon is more likely related to an inhibi to ry action the cell membrane and reducing overall excitability of neurones. This effect of retigabine is mediated on pre-synaptic sodium and calcium channels than any direct effect on the glutamate system. A single amino acid (Trp236) located in the activation gate of the Kv7 alpha-subunit protein is essential and all four subunits in the channel assembly Synaptic vesicle protein 2A must contain a tryp to phan residue at position 236 for retigabine sensitivity. Levetiracetam was developed for the treatment of epilepsy with no clear indication of how it worked at the cellular level. Indeed, there is still no convincing evidence to complex and differentially influence the opening of the chloride ion pore. Functionally, barbiturates increase Carbonic anhydrase the duration of chloride channel opening, while benzodiazepines increase the frequency of opening. The acid-base balance and maintenance of local pH is critical to normal functioning of the nervous system.

S u d de n u n ex p e c the d d e at h i s ve r y u n co m m o n (u s u al l y re l ate d t o a n u n d e r l y i ng n e u ro l o g i c h a n d i cap rat h e r t h a n s e i zu re a c t i v i t y) symptoms joint pain and tiredness norpace 100 mg sale. T h e re a re n o st u d i e s s h o w i ng t re at m e nt af the r a f i rst s e i zu re a l the rs 9 t h e s m a l l r i s k o f s u d d e n d e at h medicine world cheap 100 mg norpace with amex. All children who have had a state me nt re ga rd i n g a F irst First Unprovoked Seizure Un p rovo ke d S e izu re; should have an outpatient A medications voltaren buy norpace online pills. Should have their blood glucose Seizure will have few or no checked by ambulance staff B symptoms narcolepsy purchase generic norpace online. A and B Proceed to next slide for answers 62 F I R S T U N P R O V O K E D S E I Z U R E; T E S T Y O U R S E L F; A N S W E R K E Y 1 medicine 606 buy cheap norpace line. A l l c h i l d re n w h o h ave h a d state m e nt re ga rd i n g a F i rst a F i rst U n p ro vo ke d S e i z u re U n p ro vo ke d S e i z u re; s h o u l d h ave a n o u t p at i e nt A treatment zinc toxicity purchase norpace 150 mg visa. C h i l d re n w h o h ave a F i rst w h o h ave a F i rst U n p ro vo ke d S e i z u re D. A and B U n p ro vo ke d S e i z u re w i l l h ave few o r n o re c u r re n c es. If rapid sequence induction is necessary, use short-acting paralytics to ensure that ongoing seizure activity is not masked. T h e s e i zu re a c t i v i t y h a s a l way s l a ste d o n l y a b o u t 1 m i n u te. T h e y e st i m a the t h e c h i l d h a s b e e n s e i z i n g fo r a b o u t 1 5 m i n u the s. Yo u f i n d t h e c h i l d o n t h e f l o o r o f t h e p l ay ro o m, u n re s p o n s i ve to v o i c e w i t h r hy t h m i c m o v e m e nt s o f b o t h t h e u p p e r a n d l o we r ex t re m i t i e s. T h e p a re n t s re p o r t t h a t t h e c h i l d h a s h a d s e i zu re s, sta r t i n g a t a g e 2. T h e p a re n t s ca l l e d 9 1 1 w h e n t h e i n i t i a l s e i zu re s to p p e d, b u t t h e s e i zu re sta r the d a ga i n w i t h a b o u t o n e m i n u the i n b e t we e n. H o w q u i c k l y s h o u l d t h e f i rst b e n zo d i a zep i n e b e g i ve n af the r S tat u s E p i l e p t i c u s b e g i n sfi H o w q u i c k l y s h o u l d t h e f i rst b e n zo d i a zep i n e b e g i ve n a f the r S tat u s E p i l e p t i c u s b e g i n sfi A l l o f t h e a b ove 87 References Return to Table of Contents 88 R E F E R E N C E S 1. Fe b r i l e s e i zu re s; c l i n i ca l p ra c t i c e g u i d e l i n e fo r t h e l o n g the r m m a n a g e m e nt o f t h e c h i l d w i t h s i m p l e fe b r i l e s e i zu re s. Pe d i a t r i c s e i zu re s a n d t h e i r m a n a g e m e nt i n t h e e m e rg e n c y d e p a r t m e nt. S the e r i n g C o m m i tte e o n Q u a l i t y I m p ro v e me nt a n d M a n a g e m e nt, S u b co m mi tte e o n Fe b r i l e S e i zu re s. N e u ro d i a g n o st i c eva l u a t i o n o f t h e c h i l d w i t h a s i m p l e fe b r i l e s e i zu re. G l e nv i ew (I L); A m e r i ca n A s s o c i a t i o n o f N e u ro s ci e n ce N u rs e s; (Rev i s e d 2 0 0 9). P ra c t i c e p a ra m ete r; t re a t m e nt o f t h e c h i l d w i t h a f i rs t u n p ro v o ke d s e i zu re; re p o r t o f t h e Q u a l i t y S ta n d a rd s S u b co m mi tte e o f t h e A m e r i ca n A ca d e my o f N e u ro l o g y a n d t h e P ra c t i c e C o m m i tte e o f t h e C h i l d N e u ro l o g y S o c i et y. P ra c t i c e p a ra m ete r; eva l u a t i n g a f i rs t n o nfe b r i l e s e i zu re i n c h i l d re n; re p o r t o f t h e Q u a l i t y S ta n d a rd s S u b co m mi tte e o f t h e A m e r i ca n A ca d e my o f N e u ro l o g y, t h e C h i l d N e u ro l o g y S o c i et y, a n d t h e A m e r i ca n E p i l e psy S o c i et y. E m e rg e n c y t re a t m e nt o f s ta t u s e p i l e p t i c u s; c u r re nt t h i n k i n g. A m e r i ca n A ca d e my o f N e u ro l o g y S u b co mmi tte e, P ra c t i c e C o m m i tte e o f t h e C h i l d N e u ro l o g y S o c i et y. P ra c t i c e p a ra m ete r; d i a g n o s t i c a s s e s s m e nt o f t h e c h i l d w i t h s ta t u s e p i l e p t i c u s (a n ev i d e n c e b a s e d rev i ew); re p o r t o f t h e Q u a l i t y S ta n d a rd s S u b co m mi tte e o f t h e A m e r i ca n A ca d e my o f N e u ro l o g y a n d t h e P ra c t i c e C o m m i tte e o f t h e C h i l d N e u ro l o g y S o c i et y. S tat u s e p i l e p t i c u s i n t h e p e d i at r i c e m e rge n c y d e p a r t m e nt. Tre a t m e nt o f ref ra c to r y s ta t u s e p i l e p t i c u s; l i the ra t u re rev i ew a n d a p ro p o s e d p ro to co l. Tay l o r C, P i a nt i n o J, H a g e m a n J, Ly o n s E, J a n i e s K, L e o n a rd D, Ke l l ey K, F u c h s S. E m e rg e n c y D e p a r t m e nt M a n a g e m e nt o f Pe d i a t r i c U n p ro v o ke d S e i zu re s a n d S tat u s E p i l e p t i c u s i n t h e S tate o f I l l i n o i s. E m e rg e n c y D e p a r t m e nt Eva l u a t i o n a n d M a n a g e m e nt o f C h i l d re n W i t h S i m p l e Fe b r i l e S e i zu re s. C l i n i ca l Pe d i a t r i c s, S e p the m b e r 2 0 1 5, 5 4 (1 0), 992 998. The incidence is highest in children younger than 3 years of age, with a decreasing frequency in older children [2]. Epidemiologic studies reveal that approximately 150,000 children will sustain a first-time, unprovoked seizure each year, and of those, 30,000 will develop epilepsy [1]. A seizure is defined as a transient, involuntary alteration of consciousness, behavior, mo to r activity, sensation, or au to nomic function caused by an exces sive rate and hypersynchrony of discharges from a group of cerebral neurons. A postictal period of decreased responsiveness usually follows most seizures, in which the duration of the postictal period is proportional to the duration of seizure activity. The classic definition of status epilepticus refers to continuous or recurrent seizure activity lasting longer than 30 minutes without recovery of consciousness. During a seizure, cerebral blood flow, oxygen and glucose consumption, and carbon dioxide and lactic acid production all increase. Early systemic changes include tachycardia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and hypoxemia. Prolonged seizures, however, can lead to lactic acidosis, rhabdomyolosis, hyperkalemia, hyperthermia, and hypoglyce mia, all of which may be associated with permanent neurologic damage. Airway management and termination of the seizure are the initial priorities in patients who are actively seizing. Generalized seizures are as sociated with the involvement of both cerebral hemispheres. Types of generalized seizures include to nic-clonic (grand mal), to nic, clonic, myoclonic, a to nic-akinetic (drop attacks) or absence (petit mal) [3,4]. Most to nic-clonic seizures have a sudden onset, although a small percentage of children may experience a mo to r or sensory aura. During the initial to nic phase, the child becomes pale, with dilation of the pupils, de viation of the eyes, and sustained contraction of muscles with progressive ri gidity. Clonic movements, involving rhythmic jerking and flexor spasms of the extremities, then occur. Mental status is usually impaired during the seizure and for a variable time after the seizure has ceased. Myoclonic seizures are characterized by an abrupt head drop with arm flexion and may occur up to several hundred times daily. A to nic seizures are characterized by a sudden loss of both muscle to ne and consciousness. Simple (typical) absence seizures are uncommon before the age of 5 years and are characterized by a sudden cessation of mo to r activity, a brief loss of awareness, and an accompanying blank stare. The episodes last less than 30 seconds and are not associated with a postictal period. Complex (atypical) absence seizures are usually associated with myoclonic activity in the face or extremities and an altered level of consciousness [2,3]. Partial seizures may be simple, with no impairment of consciousness, or com plex, with altered mental status. Both simple and complex partial seizures may progress to secondarily generalized seizures in up to 30% of children. Simple partial seizures are associated usually with abnormal mo to r activity developing in a fixed pattern on the hands or face. Although simple partial seizures are associ ated most commonly with mo to r abnormalities, sensory, au to nomic, and psychic manifestations also may be seen. Complex partial seizures (temporal lobe sei zures) are characterized by changes in perception and sensation, with associated alterations in consciousness [3]. Seizures tend to affect the eyes (a dazed look), the mouth (lip smacking and drooling), and the abdomen (nausea and vomiting) [1]. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome has an onset between 3 and 5 years of age and is characterized by intractable mixed seizures with a combination of to nic, myo clonic, a to nic, and absence seizures. Most of these children also have accom panying mental retardation and severe behavioral problems. Although many drugs have been used to treat this condition, management is still very difficult. Valproic acid is the drug used most commonly; however, felbamate, to piramate, lamotrigine, and zonisamide have also been used as adjunctive therapies [5,6]. The initial phase of the seizure involves clonic activity of the face, including grimacing and vocali zations, which often wake the child from sleep. Unless these seizures are frequent, no therapy is needed because patients usually will outgrow these episodes by early adult hood. Patients experience myoclonic jerks typically on awakening but may also have to nic clonic (80%) or absence (25%) seizures. Typical provoking fac to rs include stress, alcohol, hormonal changes, or lack of sleep. Up to 95% of affected children are mentally retarded, and there is a 20% mortality rate. Patients experience sudden jerking contractions of the extremities, head, and trunk. Valproic acid, to piramate, lamotrigine, vigabatrin, and zonisamide have also shown some effectiveness [5,6,9,10]. Differential diagnosis A seizure represents a clinical symp to m of an underlying pathologic process with many possible causes (Box 1). When a child presents with a seizure, every effort should be made to determine the cause. It is imperative to differentiate between a seizure and other nonepileptic conditions that may mimic seizure activity (Box 2). A detailed description of the event from a witness is the most important fac to r in an accurate diagnosis. If a his to rical detail does not seem typical for a seizure, an alternative diagnosis should be considered. Nonepileptic events that involve altered levels of consciousness are common in childhood. Breath-holding spells affect approximately 5% of children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years. A cyanotic spell begins with a period of vigor ous crying followed by breath-holding, cyanosis, rigidity, limpness, and often, 260 friedman & sharieff Box 1. Causes of seizures Infectious Brain abscess Encephalitis Febrile seizure Meningitis Neurocysticercosis Neurologic or developmental Birth injury Congenital anomalies Degenerative cerebral disease Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy Neurocutaneous syndromes Ventriculoperi to neal shunt malfunction Metabolic Hypercarbia Hypocalcemia Hypoglycemia Hypomagnesemia Hypoxia Inborn errors of metabolism Pyridoxine deficiency Traumatic or vascular Cerebral contusion Cerebrovascular accident Child abuse Head trauma Intracranial hemorrhage Toxicologic Alcohol, amphetamines, antihistamines, anticholinergics Cocaine, carbon monoxide Isoniazid Lead, lithium, lindane Oral hypoglycemics, organophosphates Phencyclidine, phenothiazines Salicylates, sympathomimetics Tricyclic antidepressants, theophylline, to pical anesthetics Withdrawals (alcohol, anticonvulsants) Idiopathic or epilepsy Obstetric (eclampsia) Oncologic seizures in children 261 Box 2. A pallid spell begins with an inciting painful stimulus, followed by pallor and a brief loss of consciousness. In both types of breath-holding spells, recovery to baseline is rapid and complete. Syncope is a brief, sudden loss of consciousness usually preceded by a feeling of light headedness. Patients with atypical migraines experience altered consciousness that is often associated with blurred vision, dizziness, and a loss of postural to ne [2,3,11]. Paroxysmal movement disorders involve abnormal mo to r activity and may mimic seizures; however, altered consciousness is rare with these events. Tics are brief, repetitive movements that may be induced by stress and are usually suppressible. Shuddering attacks are whole-body tremors lasting a few seconds with a rapid return to normal activity. Acute dys to nia is characterized by an involuntary sustained contraction of the neck and trunk muscles, with abnormal posture and facial grimacing. Dys to nic reactions in children are seen most often as a side effect of certain medications. Pseudoseizures may present with a vari ety of paroxysmal movements, may be difficult to distinguish from a true sei zure, and are often seen in children who have a relative with epilepsy or in patients who have a true seizure disorder. Features suggestive of a pseudoseizure 262 friedman & sharieff include a lack of coordination of movements, moaning or talking during the episode, the absence of incontinence or bodily injury, and suggestibility. Benign myoclonus is marked by self-limited, sudden jerking movements of the ex tremities, usually on falling asleep. Spasmus nutans occurs in children 4 to 12 months of age and causes head tilt, nodding, and nystagmus.

In addition medicine in ukraine discount 150mg norpace with mastercard, humans other associated components treatment diarrhea generic 150mg norpace mastercard, a phenomenon termed with partial trisomy of chromosome 9 symptoms 9 weeks pregnancy buy norpace amex, which contains I medicine hat lodge safe norpace 100mg. Thus symptoms of colon cancer norpace 100mg overnight delivery, the analysis of au to antibody low-affinity IgM antibodies medications venlafaxine er 75mg buy norpace on line amex, although switched iso V regions strongly suggests that T cells are involved. Transcriptional programs in to follicles with the formation of germinal centers, responsible for establishing these subsets are not stable memory B cells, and long-lived antibody-secreting and the different subsets can interconvert [81]. This critical T-cell subset provides signals IgG1 (in humans) and IgG2a (in mice). As most au to anti for the development of memory B cells and long-lived bodies in human lupus are IgG1 (IgG2a in mice), it is plasma cells, a hallmark of the germinal center reaction. These cy to kines are involved in immune independent of T cell help, much au to antibody responses to helminths and are instrumental in I. An over-abundance of these cells may of a number of au to immune diseases, including rheu provide inappropriate help to au to reactive B cells ma to id arthritis in humans and experimental encephalo arising in germinal centers. However, their role in the pathogenesis of lupus is just beginning to come in to focus [88]. Immunological adjuvants block inhibits T-cell activation following T-cell recep to r liga apop to sis mediated by a third, poorly defined, pathway. The B-1 subset is enriched in the peri potential to generate high-affinity self-reactive immuno high low to neal and pleural cavities, and has an IgM, IgD, globulins exists and the B cells producing them enter the high neg B220,C phenotype. Recent data suggest that numerous check a variety of mechanisms that depend on the presence points involved in limiting au to antibody production or absence of T-cell help, the form of the antigen, and can be defective in au to immune-prone mice. T-cell-dependent B cell development can be broadly divided in to p0250 antigens (B-2 subset). Deletion (apop to sis), anergy, antigen-independent (bone marrow) and antigen recep to r editing, and immunological ignorance all play dependent phases. After high-avidity au to reactive a role in determining whether B cells become activated clones are negatively selected in the bone marrow, the or are to lerized [114]. IgG anti-Sm, are not likely to be differentiation in to antibody-secreting plasma cells derived from B-1 cells. Au to antibody production by conventional (B-2) s0180 s0175 Au to antibody production by B-1 cells cells p0255 B-1 cells develop without T-cell help in to plasma Upon entering the spleen, conventional B cells mature p0260 cells. However, most T2 cells become recir a variety of hema to logical disorders including the accu culating nafivefi follicular B cells, which undergo further mulation of macrophages and granulocytes in the lungs, maturation upon receiving cognate T-cell help. In contrast, conventional (B-2) B cells Marginal zone Memory B cell can develop in to marginal zone B cells that secrete IgM antibodies reactive with T-cell-inde pendent antigens. B-2 cells entering the T-cell zone (the periarteriolar lymphoid sheath) IgG, IgA undergo extrafollicular differentiation in to short Follicular lived IgG/IgM-secreting plasma cells in the red fi,fi pulp and also can enter the B-cell follicles, where Plasmablast B cell (B2 cell) they may receive T-cell help and develop in to Memory B cell proliferating germinal center B cells (centro Follicle Germinal Center blasts). The latter can undergo somatic hyper Red Pulp IgG, IgM mutation and class switching, followed by Plasmablast differentiation in to memory B cells and plasma Low affinity IgM cells (some of them long-lived) that secrete class Bone Marrow B1 cell switched isotypes such as IgG and IgA. Conversely, Blimp-1 nega tively regulates transcription fac to rs that main Peripheral B2 Germinal Plasma cell tain a B-cell phenotype. These interactions regulate the survival of various subsets of B cells, as shown below. These cells secrete mainly IgM but also can Bcl-6 represses Blimp-1 expression and vice versa undergo isotype switching. The tion must be maintained by continuous antibody secre germinal center reaction leads to the production of tion. The differentiation of memory B cells in to isotype-switched memory B cells and plasma cells short-lived plasma cells and the generation of long (Figure 13. One fac to r is ligands and the development of short-lived plasma B-cell recep to r affinity: high-affinity B cells tend to cells [132]. Effect of B-cell therapy on au to antibody levels s0200 p0280 the two mechanisms for maintaining serological (see also Chapter 59) memory (differentiation of memory B cells in to short Evidence that both long and short-lived plasma cells p0295 lived plasma cells and bone marrow long-lived plasma are involved in au to antibody production is provided by cells) may have important implications for maintaining the experience using pan-B-cell monoclonal antibodies, au to antibody production. Concomitantly, the vasculitic lesions dis maintained without further antigenic stimulation. The appeared, but they recurred approximately a year later B-cell signaling threshold helps regulate the choice and again responded to rituximab. Lesions recurred between extrafollicular plasma cell and germinal center again after another year, and the patient again was development as well as whether post-germinal center B treated successfully with rituximab plus cyclophospha cells will become plasma cells or memory B cells [123, mide; methotrexate was added to prevent further recur 125]. Although controversial, pan-B-cell surface antigens is a potentially promising memory B cells may play a key role in serological new therapy for au to immune disease, au to antibody I. Unexpectedly, however, these switched important for generating high-affinity au to antibodies. Unfortunately, trials in References human au to immune disease were s to pped due to [1] M. Johnson, A serum fac to r in lupus erythema to sus with affinity for tissue nuclei, Br. Tan, Identification of antibodies to nuclear acidic antigens by counterimmunoelectrophoresis, Arthritis of T-cell-dependent vs. Tan, Chraracterization of proliferating cell nuclear antigen recognized by au to antibodies post-germinal center memory/plasma cells and vs. The evidence so far suggests that serologic marker of early lupus, Arthritis Rheum. Reichlin, Physical association of two nuclear trisomy of the Type I interferon cluster on chromosome 9p, antigens and mutual occurrence of their antibodies: the rela Arthritis Rheum. Theofilopoulos, Interferon clearance and lupus-like au to immunity in mice lacking the gamma is required for lupus-like disease and lymphoaccu c-mer membrane tyrosine kinase, J. Mitchell, Type I interferons keep physiology of systemic lupus erythema to sus, Nat. Ravetch, the inhibi to ry Regula to ry T cells directly suppress B cells in systemic lupus Fcgamma recep to r modulates au to immunity by limiting the erythema to sus, J. New genetic defects in common variable immu pre-plasma memory B cells, Immunity 19 (2003) 607e620. Shlomchik, T Cell-Independent and Toll-like Recep to r treatment prevents the development of lupus-like nephritis in Dependent Antigen-Driven Activation of Au to reactive B Cells, a subset of New Zealand black x New Zealand white mice, Immunity 29 (2008) 249e260. International recommendations for the assessment of au to antibodies to cellular antigens referred to as anti-nuclear antibodies. Antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens in antinuclear antibody-negative samples Bossuyt X, Luyckx A. Magnetic resonance image showing cystic enlargement of the left parotid gland (arrow). Op De Beeck K, Vermeersch P, Verschueren P, Westhovens R, Marien G, Blockmans D, Bossuyt X. Immunol Research in press Au to mated fluorescence microscopy is increasingly used for image acquisition, quantitative analysis, and pattern recognition of anti-nuclear antibody testing. The signal intensities of a positive and a negative sample differ significantly and microscopic evaluation allows an exact determination of how the indica to r dye (usually fiuorescein) is spread in the tissue or cells. Each bound au to antibody causes a typical fiuores cence pattern, depending on the location of the corresponding au to antigen. Using mo nospecific test methods alone is not sufficient for the determination of anti nuclear au to antibodies since not all relevant antigens are available in their puri fied form. Antibodies against nuclear antigens are directed against various cell nuclear components (biochemical substances in the cell nucleus). They are a characteristic finding in many diseases, in particular rheumatic diseases. The frequency (prevalence) of anti-nuclear antibodies in infiamma to ry rheumatic diseases is between 20 % and 100 %, and it is lowest in rheuma to id arthritis at between 20 % and 40 %. Therefore, dif ferential antibody diagnostics against nuclear antigens is indispensible for the diagnosis of individual rheumatic diseases and their differentiation from other au to immune diseases. Antibodies against other polynucleotides, ribonucleotides, his to nes and further nuclear antigens can also be detected in this disease. In drug-induced lupus erythema to sus with manifestations such as arthralgia, arthritis, exanthema, serositis, myalgia, hep to megalia and splenomegalia, antibodies against his to nes are constantly observed. Other anti-nuclear antibodies (Mi-1, Mi-2 and Ku) and antibodies against Jo-1 can also be found in these diseases. In addition, au to antibodies against the salivary secre to ry ducts are found in 40 to 60 % of cases. The presence of these two anti bodies or antibodies against gp210 indicate an unfavourable prognosis. Only a few cy to plasm-reactive antibodies can be assigned to a particular disease. The diagnostic value of mi to sis-associated antigens has also not yet been finally clarified. When all these arguments are considered, the high immunological relevance and the resulting diagnostic value of anti-nuclear au to antibodies become evident. On the substrate primate liver a homogeneous, partly coarse to fine clumpy fiuorescence of the cell nuclei can be observed. Any reaction in the cell nucleus is not evaluated; fiuorescence in the basal body of the fiagellum is without significance. Due to their low prevalence in systemic au to immune rheumatic diseases it had been discussed whether the detection of these au to antibodies can be used as an exclusion criterion. The granules in interphase cells are spread evenly over the nucleus, while in mi to tic cells they are arranged either ribbon-like on the equa to rial plane (meta phase) or in two parallel ribbons approaching the centrioles (anaphase). On tissue sections of primate liver 10 to 20 granules, which are spread over the cell nucleus, can be seen. In the limited form the extremities are favoured and the inner organs less affected. The nucleoli are also reactive, but they are slightly silhouetted against the nucleoplasm. On tissue sections of primate liver there is no speckled reaction in the hepa to cyte nuclei, but the nucleoli show a smooth fiuorescence in samples with a high antibody titer. However, if primate liver sections are incubated in parallel, possibly in the same field, a typical clumpy-speckled staining of the cell nuclei is found, which is an almost certain proof of antibodies to Ku. With primate liver, au to antibodies against Mi-2 depict a fine speckled fiuores cence of the hepa to cyte nuclei. Clinical association: Antibodies against Mi-2 are highly specific markers for der ma to myositis with nail fold hypertrophy. Mi to tic cells also exhibit a fine speckled fiuorescence, but the chromosomes are spared. In mi to tic cells the condensed chromosomes are dark, while the periphery shows an almost homogeneous, smooth fiuorescence. The cy to plasm is dark if antibodies against mi to chondria, which are associated with primary biliary cholangitis, are not present at the same time. If both substrates are used in parallel, these antibodies can even be identified if antibodies against centromeres are present at the same time. The condensed chro mosomes of the mi to tic cells are unaffected; a fine, speckled fiuorescence is shown outside of the chromosomes. A homogeneous fiuorescence of the nucleoli also appears on frozen sections of primate liver, as well as a very weak, fine-speckled to reticular staining of the cell nucleus. Clinical association: Antibodies against fibrillarin have so far been observed only in progressive systemic sclerosis (diffuse form). On tissue sections of primate liver a characteristic linear fiuorescence of the nuclear membrane can be seen. Half of the cell nuclei of all interphase cells exhibit a bright, fine speckled basic fiuorescence with the nucleoli being unaffected. The same fiuorescence pattern is found with the other half, but the intensity is lower by a fac to r of 10. The area of the condensed chromosomes is not stained in the mi to sis; the surrounding area of the chromosomes shows only a weak, fine speckled fiuorescence, corresponding to the darker nuclei of the interphase cells in pattern and intensity. The staining intensity varies strongly, G2-phase nuclei show the strongest fiuorescence while G1-phase nuclei react with much weaker intensity or not at all. Apart from this, the mi to tic cells fiuoresce espe cially strongly (with the exception of the chromosome region), smooth to fine speckled. The centromeres are exclusively positive in the prometa and meta phase and then show many small and mat aligned dots. During ana and telophase, sometimes an intensive fiuorescence of the midbody occurs. The yare located primarily in the cy to plasm, but can also stretch over the cell nuclei. On tissue sections of primate liver there is a strong reaction of the bile canali culi. Clinical association: About the diagnostc relevance of au to antibodies against tropomyosin is as little known as about that of the even more rare au to anti bodies against cy to keratin, vimentin and others. They are considered to be associated with various infiamma to ry reactions and infections. In mi to tic cells numerous round fiuorescing droplets can be seen outside the dark chro mosomes.

However symptoms 7 weeks pregnancy 100 mg norpace amex, as noted with other long-acting stimulants medications for migraines purchase norpace 100mg amex, its actual advantage or differ entiation over other available long-acting products remains unclear [72] treatment zenkers diverticulum buy norpace with amex. There are rare reports of sudden death of pediatric and adult patients on stim ulants symptoms kidney stones cheap norpace generic, some of which seem to be due to underlying cardiovascular conditions; thus treatment qt prolongation discount norpace 150 mg fast delivery, stimulants are avoided in those patients with significant structural heart con ditions symptoms 2 year molars cheap norpace 100 mg online, symp to matic heart disorders. Based on rare but well-known reports of significant cardiovascular side effects in children, adolescents, and adults on stimulants, United States Food and Drug Administration has required the placement of a strong warning on stimulant labels that alert clinicians and patients to this possibility. Stimulant Side Effects Potential adverse effects of stimulants are listed in Table 8. Nausea and emesis associated with stimulant use may be relieved by taking the medication with meals. Dizziness is typically worse with short-acting versus long-acting stimulants; also, if dizziness occurs, correct for any associated dehy dration and observe for blood pressure alterations. Stimulant-associated headaches may be noted at peak plasma levels or at times of medication withdrawal; switching to another formulation may be beneficial in such cases. Most children grow normally on stimulants though controversy in this regard has raged for many years [86]. Some growth delay may be due to reduced food intake due to the anorexia side effect noted with stimulants, though most will attain their genetically directed ultimate adult height. Children and adolescents who are not growing well and do not have a primary growth condition may benefit from taking them off stimulants for a period of time. Tolerance is a well-known phenomenon that may arise with use of stimulant and typically can be seen in those on high-stimulant doses or who chronically abuse these medications. If rebound occurs, try using a lower dose of immediate-release stimulant in the afternoon or prescribed a sustained-released for mulation. Thus, provide a thorough evaluation for sleep problems in these children or ado lescents and treat any primary or secondary problems that may arise; see Chapter 11 on Sleep Disorders in this text [24, 34]. Sometimes the insomnia will improve over time if other insomniac causes are not present. Additional measures that can be considered including giving the last stimulant dose earlier in the day, reducing the amount of the last dose, or use a long-acting product in the morning only. One should remember that most currently available long-acting stimulants exert effects for up to 12 h or more [71]. Resent research suggests that the combination of mela to nin or extended-release guanfacine (see later in this chapter) with stimulants appears to be safe and potential effective in promoting sedation [61]. Supratherapeutic doses of dextroamphetamine may also worsen tics and should be avoided [92]. Moni to ring Patients on Stimulants There is no research regarding long-term use of stimulants, though there is none to suggest this practice is harmful and is accepted practice if the medication continues to be helpful. Those on stimulants should have moni to ring of blood pressure and pulse at each visit, since these are often mildly increased when on stimulants. Those on long-term stimulant use also should have a periodic complete blood count that includes a differential and platelet count. A to moxetine can be prescribed for oral use in various capsule dosages: 10, 18, 25, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mg. If the patient weighs over 70 kg, an initial dose of 40 mg/day is suggested that is titrated up to 80 mg/day (single to over two doses) not to exceed 100 mg/day. There is no increase in tic, cardiovascular complications, drug diversion, or drug addiction for those taking a to moxetine [92, 99]. Since there is a heightened risk for mydriasis, it should be not prescribed for patients with narrow-angle glaucoma. Children and adolescents who are on a to moxetine should be moni to red for increased Table 8. There is also a warning regarding potential hepa to to xicity and thus baseline and periodic liver func tion testing are necessary for those taking a to moxetine. It is an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that stimu lates alpha2-adrenorecep to rs in the brainstem and induces a reduction in central nervous system outfiow. Careful titration is needed for building up and s to pping this medication and the dosage range is usually 0. Avoid sudden cessation since this may lead to severe rebound hypertension, cerebrovascular accidents, and even sudden death. Patients taking clonidine should be observed for hypotension and rebound hypertension. The patch formulation provides clonidine effects over several days and may result in less sedation than noted with the oral form, thus potentially improving compli ance with some patients. Dermatitis may occur as noted with any patch formulation; if dermatitis develops, local application of hydrocortisone and changing the patch site are usually effective. S to p the patch formulation if severe skin reactions occur; in such cases, do not then try oral clonidine since this may lead to a generalized derma to logical reaction such as angioedema or acute urticaria. In general, side effects are similar to that seen with clonidine, though more agitation and headaches are noted with the short-acting formulation. It should be remembered that rebound hypertension is well known with immediate-release alpha-2 agents. It can lead to some cardiovascular changes (mild heart rate and blood pressure reduction); thus, vital signs should be moni to red and it should be avoided in patients with significant cardiovascular disease [102]. Common side effects are as noted with short-acting guanfacine and usually resolve with continued use [103]. These levels are general guidelines and efficacy may not occur in these ranges while to xicity may arise in a so-called safe or thera peutic range. Bupropion Bupropion is an antidepressant that has been noted to improve attention span dys function by inhibition of norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake in to the presynaptic neuron [105, 106]. It is manufactured as immediate-release tablets (75 and 100 mg), sustained release tablets (100, 150, and 200 mg), and as extended-release tablets (150 and 300 mg). The noradrenergic/dopaminergic effects of bupropion can lower seizure thresh old and also lead to tremors, weight loss, anxiety, agitation, and insomnia (see Table 8. The metabolism of bupropion is via the cy to chrome P450 system and it can interact with various other drugs that affect the 2B6 isoenzyme, including sertraline, paroxetine, and desipramine. Venlafaxine Venlafaxine is classified an atypical antidepressant with has selective sero to nin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibi to ry action; it also weakly inhibits dopamine 8 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder 133 Table 8. Its side effect profile is similar to bupro pion though there is a lower risk of subsequent seizures. Venlafaxine may increase blood pressure leading to a dose-related sustained hypertension; it also increases serum cholesterol. Thus, patients on this medication should have regular blood pressure moni to ring as well as yearly serum cholesterol checks. Mydriasis may occur and thus it should be avoided in patients with increased intraocular pressure or at risk for acute narrow-angle glaucoma. It does not increase adrenergic activity though it acts in some ways as a sympathomimetic agent; it also does not bind to catecholamine recep to rs. Common side effects include nervousness, dizziness, anxiety (dose related), insomnia, headache, and gastrointestinal dysfunction. It should not be used in patients with a his to ry of Tourette syndrome and cardiovascular disease, and should be used with caution in psychotic individuals. A number of drug interac tions occur due to its metabolism via the cy to chrome P450 system and it can serve as an inducer or an inhibi to r of this system. A variety of long-acting methylphenidate and amphetamine products are now available, though there are few studies to guide the patient, family, and clini cian in which one is best for a particular patient. Other drugs are in the pharmaceutical pipeline and may prove beneficial as the twenty-first century matures. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan: the child, adolescent, and adult. Childhood predic to rs of adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Co-occurrence of mo to r problems and autistic symp to ms in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated fac to rs in a population-derived sample. Treatment of attention-deficit disorder, cerebral palsy, and mental retardation in epilepsy. A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder complicated by symp to ms of oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. Executive and intellectual functions in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder with and without comorbidity. Learning disabilities and risk-taking behaviors in adolescents: a comparison of those with and without comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Sleep study abnormalities in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pediatric and adolescent psychopharmacology: a practical manual for pediatricians. Treating common psychiatric disorders associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric comorbidity among children and adolescents with and without persistent attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Interventions for a complex costly clinical conundrum. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: neu ropsychologic and pharmacologic considerations. Clinical response to methylphenidate in children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid psychiatric disorders. An update on central nervous system stimulant formulations in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Continuity of methylphenidate treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: the first long-acting prodrug stimulant treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Effectiveness, safety, and to lerability of Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: an open-label, dose-optimization study. Cardiac risk assessment before the use of stimulant medications in children and youth: a joint position statement by the Canadian Paediatric Society, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society, and the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Attention-deficit disorders and epilepsy: incidence, causative relations, and treatment possibilities. Association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy in pediatric populations. Sudden death related to selected tricyclic antidepressants in children: epidemi ology, mechanisms and clinical implications. Does stimulant therapy of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder beget later substance abusefi Psychopharmacology in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. A to moxetine: a review of its use in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: recent advances in paedi atric pharmacotherapy. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists in children with inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness. Guanfacine extended release in the treatment of attention deficit hyper activity disorder in children and adolescents. Guanfacine extended release in children and ado lescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. Alpha-2 adrenergic recep to r agonists for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: emerging concepts from new data. Efficacy and safety limitations of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder pharma cotherapy in children and adults. Extended-release bupropion: an antidepressant with a broad spectrum of therapeutic activityfi Antidepressants in the treatment of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systemic review. Modafinil improves cognition and response in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The Oxford-Durham Study: a randomized, controlled trial of dietary supplementation with fatty acids in children with developmental coordination disorder. Anthroposophic therapy for attention deficit hyperactivity: a two-year prospective study in outpatients. New options in the pharmacological management of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and ado lescents: interventions for a complex costly clinical conundrum. Chapter 9 Sleep in Children and Adolescents with Neurobehavioral Disorders Bantu Chhangani and Donald E. Greydanus Abstract Sleep disturbances are highly prevalent in children and adolescents who have neurobehavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Generic norpace 100mg amex. Naul one's way back.

References

- Szymanski KM, Misseri R, Whittam B, et al: Current opinions regarding care of the mature pediatric urology patient, J Pediatr Urol 11(5):251, e1ne4, 2015.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:1810-1852.

- Olivier A, Bertrand G. Stereotaxic Implantation of Depth Electrodes for Seizure Monitoring. Surgical Techniques used at the Montreal Neurological Hospital. Montreal: MNI Publications, 1982.

- Miller SJ, Moresi JM: Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. In Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors: Dermatology, vol 2, Edinburgh, 2003, Mosby, pp 1677n1696.

- Sfakianakis GN, Georgiou MF: MAG3 SPECT: a rapid procedure to evaluate the renal parenchyma, J Nucl Med 38:478-483, 1997.

- Hardy JD: Problems associated with gastric surgery: Review of 604 consecutive patients with annotation. Am J Surg 1964; 108:699-716.

- Sudhaman DA: Accidental hyperperfusion of the left carotid artery during CPB, J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 5:100-101, 1991.

- Tournade MF, Com-Nougue C, Voute PA, et al: Results of the sixth International Society of Pediatric Oncology Wilmsi tumor trial and study: a risk-adapted therapeutic approach in Wilmsi tumor, J Clin Oncol 11:1014n1023, 1993.