Peter C. Gerszten, MD, MPH, FACS

- Associate Professor

- Department of Neurological Surgery and Radiation Oncology

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

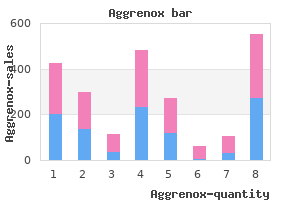

The trial medications 142 aggrenox caps 25/200 mg lowest price, with a cohort of 414 patients symptoms 6 days post iui order 25/200mg aggrenox caps visa, was powered to exclude a 3% probability of detecting a patient during surveillance only treatment of tuberculosis generic aggrenox caps 25/200mg amex, with a relapse presenting already-metastatic disease with ‘intermediate’ or ‘poor’ prognosis features symptoms dust mites 25/200 mg aggrenox caps with amex. If a relapse occurs treatment of chlamydia aggrenox caps 25/200mg online, it is generally in the chest symptoms 3 weeks pregnant order aggrenox caps, neck or at the margins of the surgical field. The need for repeated and long-term assessment of the retroperitoneum is still not clear. In 15-20% of cases there is nodal radiological involvement at the level of the retroperitoneum and only 5% of patients present with distant metastasis. The relapse rate varies between 1% and 20% depending on the post-orchiectomy therapy chosen. Consequently, in most cases, measurement of blood markers will not be a reliable test for follow-up [231]. The treatment options post-orchiectomy in stage I seminoma are surveillance or adjuvant carboplatin chemotherapy. The rate of relapse is 1-2% and the most common time of presentation is within 18 months of treatment [90, 233-235], although late relapses have also been described [210]. The site of relapse is mainly at the supradiaphragmatic lymph nodes, mediastinum, lungs or bones. In a small proportion of cases, the tumour will relapse in the inguinal or external iliac nodes. The median time to relapse ranges from 12-18 months, but up to 29% of relapses can develop later than this [81, 243]. Due to the high and often late rate of relapse, close and active follow-up is mandatory for at least 5 years [238] (see Table 8. In general, this treatment is well tolerated, with only mild, acute and intermediate-term toxicity [238, 239]. In advanced metastatic germ-cell tumours, the extent of the disease correlates with the response to therapy and with survival. The combination of cisplatin-based chemotherapy and surgery (aggressive multimodality) achieves cure rates of between 65% and 85%, depending on the initial extent of disease [241, 242]. Complete response rates to chemotherapy are in the order of 50-60% [241]; another 20-30% of patients could be disease-free with post-chemotherapy surgery [248]. Patients should be informed before treatment of common long term toxicities, which are probably best avoided by adherence to international guidelines. During follow-up, patients should be screened and treated for known risk factors such as high blood pressure, hyperlipidaemia and testosterone deficiency. The following overview is not complete and interested readers are referred to review articles on this topic [250, 253, 254]. This is possibly due to long-term depression of the bone-marrow, but also complications of subsequent salvage treatment (which was not reliably registered) or extensive or subsequent surgical treatment might lie behind these numbers. Bleomycin-induced lung toxicity may affect 7% to 21% of patients in the long term, resulting in death in 1%-3% [265]. Intriguingly, pulmonary complications were associated with the cumulative cisplatin dose and not to the dose of bleomycin. Cisplatin is believed to contribute to cold-induced vasospasms, as Vogelzang et al. Application of five or more cycles increases the frequency of this symptom to 46%. Paclitaxel-induced acute neuropathy consists of an acute pain syndrome, which usually develops within three days of paclitaxel administration, or within a week. Both hearing impairment and tinnitus are considerably increased after application of 50 mg/m2 cisplatin over two days as compared to 20 mg/m2 over five days (odds ratio 5. Hopefully, increasing insight into the pathogenesis of and vulnerability for this complication will lead to more individualised treatment in the future. After one and two years, one third of patients reported an improvement in global QoL after chemotherapy, while one fifth of patients reported deterioration, with no difference between treatment groups. These tumours are most common in the third to sixth decade in adults, with a similar incidence observed in each decade. They are solid, yellow to tan in colour, with haemorrhage and/or necrosis in 30% of cases. Microscopically, the cells are polygonal, with eosinophilic cytoplasm and occasional Reinke crystals, regular nucleus, solid arrangement and capillary stroma. The cells express vimentin, inhibin, protein S-100, steroid hormones, calretinin and cytokeratin (focally) [25]. The proportion of metastatic tumours in all published case reports is less than 10%. In three old series with long follow-up, 18 metastatic tumours were found in a total of 83 cases (21. On rare occasions, these tumours may develop in patients with androgen insensitivity syndrome and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. The arrangement of the cells is tubular or solid; a cord-like or retiform pattern is possible. The stroma is fine with capillaries, but in some cases a sclerosing aspect predominates. The cells express vimentin, cytokeratins, inhibin (40%) and protein S-100 (30%) [300]. Hormonal disorders are infrequent, although gynaecomastia is sometimes seen [300]. Only the large cell calcifying form has a characteristic image with bright echogenic foci due to calcification [308]. In general, affected patients are older, tumours are nearly always palpable, and show more than one sign of malignancy [300]. The large cell calcifying form is diagnosed in younger men and is associated with genetic dysplastic syndromes (Carney’s complex [309] and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome [310] or, in about 40% of cases, endocrine disorders. Forty-four percent of cases are bilateral, either synchronous or metachronous, and 28% show multifocality with good prognosis [305]. It has been suggested that discrimination between an early and late onset type may define a different risk for metastatic disease (5. The sclerosing subtype is very rare, unilateral, with a mean age around 40 years and metastases are infrequent [307]. In patients with symptoms of gynaecomastia or hormonal disorders, a non-germ-cell tumour should be considered and immediate orchidectomy avoided. In cases with germ-cell tumour in either frozen section or paraffin histology, orchidectomy is recommended as long as a contralateral normal testicle is present. When diagnosed and treated early, long-term favourable outcomes are seen at follow-up in Leydig cell tumours, even with its potential metastatic behaviour. Tumours that have metastasised to lymph nodes, lung, liver or bone respond poorly to chemotherapy or radiation and survival is poor [312]. It is the most frequent congenital testicular tumour and represents about 1-5% of all prepubertal testicular neoplasms. The typical morphology is a homogeneous, yellow-grey tumour, with elongated cells with grooves in microfollicular and Call-Exner body arrangements [317]. Lymphovascular invasion, necrosis, infiltrative borders and size > 4 cm may help in identifying cases with aggressive behaviour. There is limited experience with incompletely differentiated sex cord/gonadal stromal tumours and no reported cases of metastasis [32]. However, the clinical behaviour most likely reflects the predominant pattern or the most aggressive component of the tumour [320]. If the arrangement of the germ cells is in a nested pattern and the rest of the tumour is composed of sex cord/gonadal stroma, the term gonadoblastoma is used. The prognosis correlates with the invasive growth of the germinal component [321, 322]. In the case of a diffuse arrangement of the different components, there are some doubts about the neoplastic nature of the germinal cells and some authors consider them to be entrapped rather than neoplastic [323]. Microscopically, the aspect is identical to their ovarian counterparts, and their evolution is similar to that of the different epithelial ovarian subtypes. Benign (adenoma) and malignant (adenocarcinoma) variants have been reported, with malignant tumours showing local growth with a mortality rate of 40% within one year [324]. Increasing incidence of testicular cancer in the United States and Europe between 1992 and 2009. Recent trends in the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors in the United States. Innovations in health care and mortality trends from five cancers in seven European countries between 1970 and 2005. German second-opinion network for testicular cancer: sealing the leaky pipe between evidence and clinical practice. Is surveillance for stage 1 germ cell tumours of the testis appropriate outside a specialist centre? Impact of the treating institution on survival of patients with “poor-prognosis” metastatic nonseminoma. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genito Urinary Tract Cancer Collaborative Group and the Medical Research Council Testicular Cancer Working Party. Population-based study of perioperative mortality after retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumors. Long-term oncological outcome after post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in men with metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumour. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome comprises some but not all cases of hypospadias and impaired spermatogenesis. A meta-analysis of the risk of boys with isolated cryptorchidism developing testicular cancer in later life. The association risk of male subfertility and testicular cancer: a systematic review. Familial testicular germ cell tumors in adults: 2010 summary of genetic risk factors and clinical phenotype. Tallness is associated with risk of testicular cancer: evidence for the nutrition hypothesis. Is increased body mass index associated with the incidence of testicular germ cell cancer? Early predicted time to normalization of tumor markers predicts outcome in poor prognosis nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Improved accuracy of computerized tomography based clinical staging in low stage nonseminomatous germ cell cancer using size criteria of retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Metastases to retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes: computed tomography and lymphangiography. Chest staging in testis cancer patients: imaging modality selection based upon risk assessment as determined by abdominal computerized tomography scan results. The role of positron emission tomography in the evaluation of residual masses after chemotherapy for advanced stage seminoma. Value of pre and post-orchiectomy serum tumor marker information in prediction of retroperitoneal lymph node metastases. Contralateral testicular biopsy procedure in patients with unilateral testis cancer: is it indicated? The International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: a new prognostic factor based staging classification for metastatic germ cell tumours. Ultrasonography as a diagnostic adjunct for the evaluation of masses in the scrotum. Clinicopathological study of regressed testicular tumors (apparent extragonadal germ cell neoplasms). Prevalence of contralateral testicular intraepithelial neoplasia in patients with testicular germ cell neoplasms. Carcinoma in situ of contralateral testis in patients with testicular germ cell cancer: study of 27 cases in 500 patients. Intratubular germ cell neoplasia of the contralateral testis in testicular cancer: defining a high risk group. Incidence of contralateral germ cell testicular tumors in South Europe: report of the experience at 2 Spanish university hospitals and review of the literature. Clinical course and histopathologic risk factor assessment in patients with bilateral testicular germ cell tumors. Prevalence of carcinoma in situ and other histopathological abnormalities in testes of men with a history of cryptorchidism. Radiotherapy with 16 Gy may fail to eradicate testicular intraepithelial neoplasia: preliminary communication of a dose-reduction trial of the German Testicular Cancer Study Group. Effect of graded testicular doses of radiotherapy in patients treated for carcinoma-in-situ in the testis. Carcinoma in situ testis, the progenitor of testicular germ cell tumours: a clinical review. Treatment of testicular germ-cell cancer: a cochrane evidence-based systematic review. Risk-adapted management for patients with clinical stage I seminoma: the Second Spanish Germ Cell Cancer Cooperative Group study. Risk factors for relapse in clinical stage I nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumors: results of the German Testicular Cancer Study Group Trial. Stage I non-seminomatous germ-cell tumours of the testis: identification of a subgroup of patients with a very low risk of relapse. Impact of cytotoxic treatment on long-term fertility in patients with germ-cell cancer. Pharmacology and clinical use of testosterone, in Testosterone-Action, Deficiency, Substitution. Feelings of loss and uneasiness or shame after removal of a testicle by orchidectomy: a population-based long-term follow-up of testicular cancer survivors. Multicenter study evaluating a dual policy of postorchiectomy surveillance and selective adjuvant single-agent carboplatin for patients with clinical stage I seminoma.

Syndromes

- Diarrhea, may be watery or bloody

- Find someone to help with shopping, cooking, paying your bills, and keeping your house clean.

- Vardenafil (Levitra)

- Centipede venom

- Male: 4.7 to 6.1 million cells/mcL

- Loss of muscle function that makes you unable to move your joints

- Weight

- Dialysis

- Eat a healthy diet that is high in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fish, and lean meats

- Nutritional assessment

For most people symptoms zinc deficiency purchase aggrenox caps uk, prevention of toxoplasmosis is not a serious concern symptoms kidney cancer cheap aggrenox caps 25/200 mg fast delivery, as infection generally causes no symptoms or mild symptoms symptoms kidney cancer purchase aggrenox caps with paypal. Pregnant women symptoms dehydration generic aggrenox caps 25/200 mg with visa, women who plan to become pregnant symptoms kennel cough purchase aggrenox caps with mastercard, and immunocompromised individuals who test negative for Toxoplasma infection should take precautions against becoming infected symptoms precede an illness purchase 25/200mg aggrenox caps otc. Precautions consist in measures such as consuming only properly frozen or cooked meats, avoiding cleaning cats’ litter pans and avoiding contact with cats of unknown feeding history. American trypanosomiasis: Chagas disease Chagas disease is a serious problem of public health in Latin America, and is becoming more important in developed nations owing to the high flow of immigrants from endemic areas. Chagas disease is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, a protozoan that it is transmitted by means of triatomine insects. Up to 8% of the population in Latin America are seropositive, but only 10–30% of them develop symptomatic disease (36). The disease is a major cause of congestive heart failure, sudden death related to chronic Chagas disease, and cerebral embolism (stroke). Neuroimaging usually demonstrates the location and extent of the cerebral infarct. Secondary prevention of stroke with long-term anticoagulation is recommended for all chagasic patients with stroke and heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias or ventricular aneurisms. Traditional control programmes in Latin American countries have focused on the spraying of insecticides on houses, household annexes and other buildings. National programmes aimed at the interruption of the domestic and peridomestic cycles of transmission involving vectors, animal reservoirs and humans are feasible and have proved to be very effective. A prime example is the programme that has been operating in Brazil since 1975, when 711 municipalities had triato mine-infested dwellings: 10 years later only 186 municipalities remained infested, representing a successful accomplishment of the programme’s objectives in 74% of the originally infested areas (37). African trypanosomiasis: sleeping sickness African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness, is a severe disease that is fatal if left untreated. The causative agents are protozoan parasites of the genus Trypanosoma, which enter the bloodstream via the bite of blood-feeding tsetse flies (Glossina spp. The acute form of the disease attributable to Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, widespread in eastern and southern Africa, is closely related to a common infection of cattle known as N’gana, which restricts cattle rearing in many prime areas of Africa. Tsetse flies can acquire parasites by feeding on these animals or on an infected person. Early symptoms, which include fever and enlarged lymph glands and spleen, are more severe and acute in T. Sleeping sickness claims comparatively few lives annually, but the risk of major epidemics means that surveillance and ongoing control measures must be maintained, especially in sub Saharan Africa where 36 countries have epidemiological risk. Control relies mainly on systematic surveillance of at-risk populations, coupled with treatment of infected people. In addition, reduc tion of tsetse fly numbers plays a significant role, especially against the rhodesiense form of the disease. In the past, this has involved extensive clearance of bush to destroy tsetse fly breeding 106 Neurological disorders: public health challenges and resting sites, and widespread application of insecticides. More recently, efficient traps and screens have been developed that, usually with community participation, can keep tsetse popula tions at low levels in a cost-effective manner (38). Schistosomiasis Schistosomiasis is an infection with a relatively low mortality rate but a high morbidity rate; it is endemic in 74 developing countries, with more than 80% of infected people living in sub-Sa haran Africa. Infection is caused by trematode flatworms (flukes) of the genus Schistosoma: in freshwater, intermediate snail hosts release infective forms of the parasite. There are five spe cies of schistosomes able to infect humans: Schistosoma haematobium (the urinary form) and S. If people are in contact with water where infected snails live, they become infected when larval forms of the parasites penetrate their skin. Later, adult male and female schistosomes pair and live together in human blood vessels. Systemic complications are bladder cancer, progressive enlargement of the liver and spleen, intestinal damage due to fibrotic lesions around eggs lodged in these tissues, and hypertension of the abdominal blood vessels. Death is most often caused by bladder cancer associated with urinary schistosomiasis and by bleeding from varicose veins in the oesophagus associated with intestinal schistosomiasis. Children are especially vulnerable to infection, which develops into chronic disease if not treated. Diagnosis is made by using urine filtration and faecal smear techniques, antigen detection in endemic areas and antibody tests in non-endemic areas. The disease is controlled through an integrated approach: drug treatment with praziquantel or oxamniquine (effective only against S. Hydatidosis Cystic hydatidosis/echinococcosis is an important zoonosis caused by the tapeworm Echino coccus granulosus. The parasite is distributed worldwide and about 2–3 million patients are estimated in the world (40). It causes serious human suffering and consider able losses in agricultural and human productivity. General lack of awareness of transmission factors and prevention measures among the population at risk, abundance of stray dogs, poor meat inspection in abattoirs, improper disposal of offal and home slaughtering practices play a role in the persistence of the disease. Large prevalence studies have been conducted in many countries: in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Morocco and Tunisia, the prevalence ranged from 1% to 2%. In the normal life-cycle of Echinococcus species, adult tapeworms (3–6 mm long) inhabit the small intestine of carnivorous definitive hosts, such as dogs, coyotes or wolves, and echinococcal cyst stages occur in herbivorous intermediate hosts, such as sheep, cattle and goats. In most infected countries there is a dog–sheep cycle in which grazing sheep ingest tapeworm eggs passed in the faeces of an infected dog. Dogs ingest infected sheep viscera, mainly liver and lungs, neurological disorders: a public health approach 107 containing larval hydatid cysts in which numerous tapeworm heads are produced. These attach to the dog’s intestinal lining and develop into mature adult tapeworms. Humans become infected by ingesting food or drink contaminated with faecal material containing tapeworm eggs passed from infected carnivores, or when they handle or pet infected dogs. Oncospheres released from the eggs penetrate the intestinal mucosa and lodge in the liver, lungs, muscle, brain and other organs, where the hydatid cysts form. To control the parasite, a number of antihelminthic drugs have proved to be effective against adult stages of E. The best drug currently available is praziquantel which exterminates all juvenile and adult echinococci from dogs. Several of the benzimidazole compounds have been shown to have efficacy against the hydatid cyst in the intermediate host. Echinococcosis can be controlled through preventive measures that break the cycle between the definitive and the intermediate host. These measures include dosing dogs, inspecting meat and educating the public on the risk to humans and the necessity to avoid feeding offal to dogs. Even with the advent of effective antibiot ics and vaccines, they still remain a major challenge in many parts of the world, especially in developing countries where the worst health indicators are found. Some diseases that had been found in the developed world but have virtually disappeared, such as poliomyelitis, leprosy and neurosyphilis, are still taking their toll in developing regions. Conversely, some of the protozoan and helminthic infections that are so characteristic of the tropics are now being seen with increas ing frequency in developed countries. Other major concerns are the development of drug-resistant organisms, the increasing number of immunocompromised populations and the rising number of diseases previously considered rare. Education, surveillance, development of new drugs and vaccines, and other policies are in constant evolution to fight against old and emerging infectious diseases of the nervous system. Some preventive measures have a more rapid impact and are more cost effective than others. Regular, large-scale treatment to prevent disease is cheap, by treating carriers. Large-scale treatment in humans can be combined for several diseases (the “preventive chemotherapy” concept), and can be packaged in domestic animals — such as dogs — with other interventions such as rabies vaccination. The basic idea is to deliver such public health treatment packages regularly, to enable people to avoid the worst effects of infection, even with an ongoing lack of water, sanitation and hygiene. It has to be said that environmental measures would eventually solve the problem, but require a much more substantial investment and commitment. Some diseases are easily controlled and prevented with basic, inexpensive measures that are available worldwide, but their effectiveness entails a massive education effort and steady surveillance. Conversely, some of the protozoan and helminthic infections that are so characteristic of the tropics are now being seen with increasing frequency in developed countries. A population based, case-control study of Taenia solium taeniasis and cysticercosis. New York, World Federation of Neurology and Demos Medical Publishing, 2006:49–62 (Seminars in Clinical Neurology, in press). The burden of the neurocognitive impairment associated with Plasmodium falciparum malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. Detection, screening and community epidemiology of taeniid cestode zoonoses: cystic echinococcosis, alveolar echinococcosis and neurocysticercosis. Manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. Prevalence, incidence, and etiology of epilepsies in rural Honduras: the Salama study. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. Malnutrition affects all age groups, but it is espe cially common among poor people and those with inadequate access to health educa tion, clean water and good sanitation. In addition, it touches briefly on the ingestion of toxic substances in food or alcohol, as these also contribute to neurological disorders. Most of the malnutrition-related neurological disorders can be prevented and therefore they are of public health concern. Raising awareness in the population, among leaders and decision-makers and in the international community is important in order to adopt an appropriate health policy. The macronutrients are the energy-yielding nutrients — proteins, carbohydrates and fat — and micronutrients are the vitamins and minerals. The macronutrients have a double function, being both “firewood” and “building blocks” for the body, whereas the micronutrients are special building items, mostly for enzymes to function well. The term “malnutrition” is used for both macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies. Macronutrient and micronutrient problems often occur together, so that the results in humans are often confounded and impossible to separate out. Minerals Iodine 150 μg Iodine deficiency disorders Iron 15 mg Delayed mental development in children Zinc 12 mg Delayed motor development in children, depression Selenium 55 mg Adverse mood states a Recommended daily allowance for an adult. As a rule, general malnutrition among adults does not cause specific neurological damage, whereas among children it does. Undernutrition can be assessed most commonly by measurement of the body weight and the body height. With these two measurements, together with age and sex, it will be possible to evaluate the energy stores of the individual. The aims of the anthropometric examination are: to assess the shape of the body and identify if the subject is thin, ordinary or obese; neurological disorders: a public health approach 113 to assess the growth performance (this applies only to growing subjects, i. A person who is too thin is said to be “wasted” and the phenomenon is generally called “wasting”. Children with impaired growth are said to be “stunted” and the phenomenon is called “stunting”. The percentage of wasted children in low income countries is 8%, ranging from 15% in Bangla desh and India down to 2% in Latin America (3). This presents a disturbing picture of malnutrition among children under five years of age in underprivileged populations. These children should be an important target group for any kind of nutritional intervention to be undertaken in these countries. The global average for stunting among children in low income countries is 32% (3). Increasing evidence shows that stunting is associated with poor developmental achievement in young children and poor school achieve ment or intelligence levels in older children. To continue to allow underprivileged environments to affect children’s development not only perpetuates the vicious cycle of poverty but also leads to an enormous waste of human potential. Long-term effects of malnutrition Apart from the risk of developing coronary heart disease, diabetes and high blood pressure later in life owing to malnutrition in early life, there is now accumulating evidence of long-term adverse effects on the intellectual capacity of previously malnourished children. It is methodologically difficult, however, to differentiate the biological effects of general malnutrition and those of the deprived environment on a child’s cognitive abilities. It is also methodologically difficult to dif ferentiate the effect of general malnutrition from the effect of micronutrient deficiencies, such as iodine deficiency during pregnancy and iron deficiency in childhood, which also cause mental and physical impairments. Malnourished children lack energy, so they become less curious and playful and communicate less with the people around them, which impairs their physical, mental and cognitive development. Two recent reviews highlight the evidence of general malnutrition per se causing long-term neurological deficits (4, 5). An increasing number of studies consistently show that stunting at a young age leads to a long-term deficit in cognitive development and school achievement up to adolescence. Episodes in young childhood of acute malnutrition (wasting) also seem to lead to similar impairments. The studies also indicate that the period in utero and up to two years of age represents a particularly vulnerable time for general malnutrition (4). In addition to food supplementation, it has been nicely demonstrated that stimulation of the child has long-term beneficial effects on later performance. One such study is from Jamaica, where stunted children who were both supplemented and stimulated had an almost complete catch-up with non-stunted children (6), see Figure 3. Treatment of severe malnutrition If a child becomes seriously wasted, this in itself is a life-threatening condition.

Occasionally symptoms dehydration generic aggrenox caps 25/200 mg otc, candidiasis may be responsible and treated using Fluconazole tabs 50mg x 7 days or equivalent medications heart failure generic 25/200 mg aggrenox caps visa. Definition of staging Limited stage: No universally accepted definition of this term is available treatment notes purchase aggrenox caps 25/200mg free shipping. Timing of Thoracic Radical Radiotherapy (consolidation) Several metanalyses have indicated superior survival rates when radical radiotherapy is used early on medicine administration buy 25/200mg aggrenox caps otc, within 1st or 2nd chemotherapy cycles4 symptoms 1dpo cheap 25/200 mg aggrenox caps mastercard. Further analysis suggests that the overall duration of the radiotherapy (to be completed within 4 weeks) has advantage over longer duration radiotherapy symptoms gluten intolerance purchase aggrenox caps 25/200 mg with amex. Cancer has spread outside of the lung to other tissues in the chest or to other parts of the body (metastasized). Current disease status Treatment regimen A Previously Limited disease Radical Chemoradiotherapy untreated amenable to radical Fractionated Cisplatin & Etoposide thoracic irradiation. Monitoring investigations required at each visit: physical examination, chest x-ray and tests as indicated. Follow-up: Patients will be seen 6 weeks after completion of treatment with subsequent follow up as per local policy. Patients with sensitivity or susceptibility to carboplatin side effects may occasionally be considered. Follow-up: Patients will be seen 6 weeks after completion of treatment and subsequently according to local protocol. Occasionally the Irinotecan dose can be 100 mg/m2 at cycle one; the Irinotecan dose may also be increased to 100 mg/m2 pending toxicity (discuss with consultant). If response seen at 4 cycles a further 2 may be given at discretion of treating physician (Mitomycin is omitted after 4 cycles completed). Follow-up: Patients will be seen 6 weeks after completion of treatment then according to local follow up protocols. Intravenous Topotecan is not recommended for people with relapsed small-cell lung cancer. It may be appropriate to start with 3 consecutive days’ therapy initially, increasing to the full 5 days subsequently. Follow-up: Patients should be reviewed every 3 weeks, as this is palliative treatment. Consider relevant clinical trial E Other protocols/drugs Protocols including vinorelbine with or without cisplatin and gemcitabine with or without carboplatin, may be appropriate on occasion. Palliative Paclitaxel and Carboplatin weekly regimen or 3 weekly regimen Elisabeth Quoix, Gérard Zalcman, Jean-Philippe Oster et al. Treatment: Erlotinib 150mg once daily orally until disease progression or emergence of intolerable toxicities. N Engl J Med 361:947-957, 2009 Treatment: Gefitinib 250mg once daily orally until disease progression or emergence of intolerable toxicities. Follow-up: Monthly until disease stabilisation or response established, then consider two monthly 10. Prospective randomised trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum based chermotherapy. People who have received Pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin as first-line chemotherapy cannot receive Pemetrexed maintenance treatment. People currently receiving treatment with Erlotinib, but for whom treatment would not be recommended according to section 1. Common symptoms of lung cancer Common symptoms of lung cancer include fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss, breathlessness, cough, haemoptysis, hoarseness, chest pain, bone pain, spinal cord compression, brain metastases and superior vena caval obstruction. Thoracic symptoms have been subdivided into dyspnoea (breathlessness), including malignant pleural effusion, non-obstructive airway symptoms (cough, haemoptysis, hoarseness and chest pain) and superior vena caval obstruction. Neurological symptoms include those arising from brain metastases and spinal cord compression. The treatment of bone pain and pathological fractures is covered under a section on bone metastases. No specific evidence on the treatment of pain has been reviewed as this is a general symptom of cancer and not specific to lung cancer which is outside the scope of this chapter. Many of these symptoms can be very debilitating and considerably reduce quality of life. Some treatments with palliative intent, in addition to relieving symptoms and improving quality of life, may increase survival; this is particularly so when the underlying cause is life-threatening. The symptoms’ underlying causal mechanisms and the stage and performance status of the patient also determine the treatment given. Palliative radiotherapy Patients who cannot be offered curative treatment, and are candidates for palliative radiotherapy, may either be observed until symptoms arise and then treated, or be treated with palliative radiotherapy immediately. Managing endobronchial obstruction When patients have large airway involvement, monitor (clinically and radiologically) for endobronchial obstruction to ensure treatment is offered early. Offer external beam radiotherapy and/or endobronchial debulking or stenting to patients with impending endobronchial obstruction. Every cancer network should ensure that patients have rapid access to a team capable of providing interventional endobronchial treatments. Other palliative treatments Pleural aspiration or drainage should be performed in an attempt to relieve the symptoms of a pleural effusion. Patients who benefit symptomatically from aspiration or drainage of fluid should be offered talc pleurodesis for longer-term benefit. Non-drug interventions for breathlessness should be delivered by a multidisciplinary group, coordinated by a professional with an interest in breathlessness and expertise in the techniques (for example, a nurse, physiotherapist or occupational therapist). Patients with troublesome hoarseness due to recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy should be referred to an ear, nose and throat specialist for advice. Stent insertion should be considered for the immediate relief of severe symptoms of superior vena caval obstruction or following failure of earlier treatment. Managing brain metastases Offer dexamethasone to patients with symptomatic brain metastases and reduce to the minimum necessary maintenance dose for symptomatic response. Hypercalcaemia, bone pain and pathological fractures For patients with bone metastasis requiring palliation and for whom standard analgesic treatments are inadequate, single-fraction radiotherapy should be administered. Managing other symptoms: weight loss, loss of appetite, difficulty swallowing, fatigue and depression Other symptoms, including weight loss, loss of appetite, depression and difficulty swallowing, should be managed by multidisciplinary groups that include supportive and palliative care professionals. Palliative Radiotherapy Palliative radiotherapy remains an important and commonly used form of treatment for patients with lung cancer. Palliative radiotherapy is used to treat symptoms arising from the primary cancer or sites of secondary spread. The primary cancer may be treated when it causes symptoms such as breathlessness due to endobronchial obstruction or vascular obstruction, persistent cough, haemoptysis and chest pain. Radiotherapy regimens vary from single to multiple fractions and are given in high dose where the aim is to substantially reduce the size of the cancer. Recommendation: Patients who cannot be offered curative treatment, and are candidates for palliative radiotherapy, may either be observed until symptoms arise and then treated, or be treated with palliative radiotherapy immediately. Management of endobronchial obstruction Endotracheal or endobronchial obstruction can be classified as intrinsic, extrinsic or mixed; intrinsic obstruction is caused by a cancer within the airway lumen and extrinsic obstruction from a cancer externally compressing an airway. Tracheal obstruction is a life-threatening condition and requires urgent assessment and treatment. There are a range of treatments to prevent or treat airway obstruction including conventional external beam radiotherapy, endobronchial surgical debulking of the cancer, stenting and endoscopic endobronchial treatments. Endobronchial surgical debulking of the cancer can be undertaken using either rigid or flexible bronchoscopy. Advantages of rigid bronchoscopic procedures under general anaesthesia include the ability to remove large pieces of cancer, maintain adequate ventilation, and allow control of large volume haemorrhage. These treatments are usually given to palliate symptoms and improve quality of life, but in some patients relief of endobronchial obstruction will allow assessment for subsequent treatment with curative intent. Endobronchial techniques available are either a) used to debulk the cancer (brachytherapy, electrocautery, cryotherapy, thermal laser ablation and photodynamic therapy) or b) used to maintain/re-establish airway patency (endobronchial stenting). It was noted that thermal laser ablation, surgical debulking and stent insertion were all favoured options where immediate relief of endobronchial obstruction is required, especially if there is a relatively large cancer. Endobronchial debulking procedures are generally not suitable in cases where the predominant cause of airway obstruction is extrinsic compression. In such cases airway stenting to maintain/re-establish airway patency and/or external beam radiotherapy aimed at treating the surrounding cancer may be considered. External beam radiotherapy is effective in around two-thirds of patients and is less invasive than the other endobronchial treatments. Please see table below: Description of endobronchial treatments: 58 Recommendations: When patients have large airway involvement, monitor (clinically and radiologically) for endobronchial obstruction to ensure treatment is offered early. Pleural Effusion Breathlessness due to pleural effusion may be relieved by removal of the fluid via needle aspiration or narrow-bore indwelling catheter. However, symptomatic benefit from simple drainage is generally short lived due to re-accumulation of the fluid over days or a few weeks. Pleural aspiration or drainage should be performed in an attempt to relieve the symptoms of a pleural effusion. Non drug treatment for breathlessness the cause of breathlessness in lung cancer is often multifactorial. A thorough evaluation is important to ensure correctable causes are addressed and that appropriate drug therapies are optimised. Non-drug measures include exploring the patient’s understanding of breathlessness and its meaning, providing explanation, breathing retraining and anxiety management. Non-drug interventions based on psychosocial support, breathing control and coping strategies should be considered for patients with breathlessness. Although this support may be provided in a breathlessness clinic, patients should have access to it in all care settings. Management of cough About 80% of patients with lung cancer experience cough and one-third haemoptysis. Other anticancer treatments can also bring relief such as palliative chemotherapy and some endobronchial treatments. Recommendation: Opioids, such as codeine or morphine, should be considered to reduce cough. Management of Hoarseness About 10% of patients with lung cancer experience some hoarseness of their voice. Teflon stiffening of the vocal cord can prevent paradoxical movement and lead to some improvement in the voice. Recommendation: Patients with troublesome hoarseness due to recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy should be referred to an ear, nose and throat specialist for advice. Patients who present with superior vena cava obstruction should be offered chemotherapy and radiotherapy according to the stage of disease and performance status. Corticosteroids reduce symptoms caused by cerebral metastases by reducing cerebral oedema. The median survival of patients with brain metastases from primary lung cancer is 1–2 months when treated with corticosteroids alone. Improvement in neurological symptoms is seen in half of patients after 2 weeks and three quarters after 4 weeks. About one-third of patients presenting with cerebral metastases have a solitary lesion. There is debate about the role of chemotherapy in the treatment of cerebral metastases. Recommendations •Offer dexamethasone to patients with symptomatic brain metastases and reduce to the minimum necessary maintenance dose for symptomatic response. Spinal Cord Compression 61 Compression of the spinal cord, typically by metastatic epidural cancer, can lead to neurological impairment and paraplegia. At the time of diagnosis the most common symptom is pain, followed by weakness, autonomic dysfunction or sensory loss. Hypercalcaemia, Bone Pain and Pathological Fractures Bone is one of the most frequent sites of metastasis in lung cancer and can result in pain and pathological fracture. Methods of treating bone metastases include radiotherapy, bisphosphonates and nerve blocks. Recommendation: For patients with bone metastasis requiring palliation and for whom standard analgesic treatments are inadequate, single-fraction radiotherapy should be administered. Other symptoms: weight loss, loss of appetite, difficulty swallowing, fatigue and depression A thorough assessment is important to guide appropriate management by members of the multidisciplinary team providing holistic supportive and palliative care. Recommendation: Other symptoms, including weight loss, loss of appetite, depression and difficulty swallowing, should be managed by multidisciplinary groups that include supportive and palliative care professionals. Holistic Needs Assessment Holistic needs assessment and subsequent care plan fully completed to capture rehabilitation needs at all key points in the patient pathway including diagnosis, start of treatment, during treatment, end of treatment, progressive disease and palliative/end of life care. Follow-up care of lung cancer patients Offer all patients an initial specialist follow-up appointment within 6 weeks of completing treatment to discuss ongoing care. Offer regular appointments thereafter, rather than relying on patients requesting appointments when they experience symptoms. Following Radical Radiotherapy the patient will be seen at least once during the treatment course and again on completion. Following Chemotherapy If this treatment is given as the sole therapy, the patient will have advanced disease. Best Supportive Care this is likely to be the largest (and most symptomatic group). Their care will be completely taken over by the community and this transfer of care must be communicated to the clinics. It is not the intention of these recommendations to state the duration of time that patients with advanced disease should attend the lung cancer clinics. Some clinics will be busier than others and time must be kept to discuss the diagnosis of treatment with new patients, and also to see old patients with sudden new problems. National Institute of Clinical Excellence, the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer (update), 2011 publications. Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery. Haematologica If Grade 4 then 1 l parameters withhold until Grade 2 then resume at dose of 200mg twice daily.

Some individuals will need a more detailed assessment for work or driving (Sections 4 symptoms of a stranger buy cheap aggrenox caps on line. Clinicians should note that the presence of cognitive impairment does not necessarily mean that the individual lacks mental capacity (Section 4 jnc 8 medications discount aggrenox caps 25/200 mg mastercard. Evidence to recommendations Cognitive research usually focuses on a specific impairment meaning there is little research into general cognitive rehabilitation anima sound medicine order aggrenox caps 25/200mg with visa. Schmidt et al (2013) evaluated a self-awareness intervention based on a meal preparation activity treatment hypothyroidism purchase 25/200 mg aggrenox caps with mastercard, comparing three groups: video with verbal feedback symptoms after miscarriage discount 25/200mg aggrenox caps visa, verbal feedback alone and no feedback treatment diabetic neuropathy generic aggrenox caps 25/200mg. Video with verbal feedback was superior to the other methods but the type of brain injury was unspecified and the relevance to stroke is unclear. Alvarez-Sabin et al (2013) evaluated citicoline (a complex nucleotide composed of ribose, pyrophosphate, cytosine and choline). They cautiously concluded that citicoline showed promise on a composite score derived from multiple cognitive tests, but larger trials with functional outcomes are needed. Routine screening should be undertaken to identify the person’s level of functioning, using standardised measures. B Any person with stroke who is not progressing as expected in rehabilitation should receive a detailed assessment to determine whether cognitive impairments are responsible, with the results explained to the person, their family and the multidisciplinary team. C People with communication impairment after stroke should receive a cognitive assessment using valid assessments in conjunction with a speech and language therapist. Specialist advice should be sought if there is uncertainty about the interpretation of cognitive test results. D People with cognitive problems after stroke should receive appropriate adjustments to their multidisciplinary treatments to enable them to participate, and this should be regularly reviewed. E People with acute cognitive problems after stroke whose care is being transferred from hospital should receive an assessment for any safety risks from persisting cognitive impairments. Risks should be communicated to their primary care team together with any mental capacity issues that might affect their decision-making. F People with stroke returning to cognitively demanding activities such as driving or work should have their cognition fully assessed. G People with continuing cognitive difficulties after stroke should be considered for comprehensive interventions aimed at developing compensatory behaviours and learning adaptive skills. H People with severe or persistent cognitive problems after stroke should receive specialist assessment and treatment from a clinical neuropsychologist/clinical psychologist. People with apraxia often have problems carrying out everyday activities such as dressing or making a hot drink despite adequate strength and sensation. They may also have difficulties in selecting the right object at the right time or in using everyday objects correctly. Evidence to recommendations In the absence of new evidence of sufficient quality the recommendations have not changed. One Cochrane review found insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of strategy training, transfer of training or gesture training (West et al, 2008). Case series research suggests that the types of observed action errors are important clues for the type of retraining needed (Sunderland et al, 2006). Future research needs to provide detailed descriptions of the interventions and measure the impact on everyday function. B People with apraxia after stroke should: ‒ have their profile of impaired and preserved abilities determined using a standardised approach; ‒ have the impairment and the impact on function explained to them, their family/carers, and the multidisciplinary team; ‒ be offered therapy and/or trained in compensatory techniques specific to the deficits identified, ideally in the context of a clinical trial. Disturbed alertness is common after stroke especially in the first few days and weeks, and more so in non-dominant hemisphere stroke. Attention problems may lead to fatigue, low mood and difficulty with independent living. Evidence to recommendations Recommendations have not changed as the only new evidence of sufficient quality is one Cochrane review of six small studies (Loetscher and Lincoln, 2013). This found limited evidence that cognitive rehabilitation interventions (attention process training, time pressure management and/or computer based training 60 packages) improved some aspects of attention in the short term, but insufficient evidence for any persisting effects. B People with impaired attention after stroke should have cognitive demands reduced by: ‒ having shorter treatment sessions; ‒ taking planned rests; ‒ reducing background distractions; ‒ avoiding activities when tired. C People with impaired attention after stroke should: ‒ have the impairment explained to them, their family/carers and the multidisciplinary team; ‒ be offered an attentional intervention. The ‘dysexecutive syndrome’ encompasses various impairments, including difficulties with problem solving, planning, organising, initiating, inhibiting and monitoring behaviour. It also includes impairments in cognitive flexibility, which is the ability to change cognitive or behavioural strategies to adapt to novel or evolving task demands. The Cochrane review identified 19 trials (and selected 13 for meta-analysis) but concluded that there was insufficient high quality evidence to guide practice. B People with an impairment of executive function and activity limitation after stroke should be trained in compensatory techniques, including internal strategies. Memory deficits can lead to longer hospital stay, poorer outcomes, risks to personal safety, and cause distress to people with stroke and their family. Memory loss is a characteristic feature of dementia, which affects about 20% of people after stroke, but this section is not directly concerned with the impairments associated with diffuse cerebrovascular disease. It should also be noted that subjective memory problems can result from attentional or executive difficulties. The compensation and restitution groups used more internal memory strategies than the control group but there was no difference in outcomes. Further research is needed to establish the clinical effectiveness (at the level of activities or participation) and acceptability of memory rehabilitation approaches, recruiting larger, more representative, groups of people with stroke. B People with memory impairment after stroke causing difficulties with rehabilitation should: ‒ have the impairment explained to them, their family/carers and the multidisciplinary team; ‒ be assessed for treatable or contributing factors. Perceptual functions include awareness, recognition, discrimination and orientation. Disorders of perception are common after stroke and may affect any sensory modality. However, visual perception has been the most widely studied, particularly visual agnosia (impaired object recognition). It is important to distinguish between deficits affecting the whole perceptual field (covered in this section) and unilateral deficits (Section 4. Evidence to recommendations A Cochrane review (Bowen et al, 2011) examined the evidence for the four main intervention approaches that are used, often in combination, in clinical practice: functional training, sensory stimulation, strategy training and task repetition. The updated literature search for the current guideline did not find any further trials of effectiveness. B People with agnosia after stroke should: ‒ have the impairment explained to them, their family/carers and the multidisciplinary team; ‒ have their environment assessed and adapted to reduce potential risks and promote independence; ‒ be offered a perceptual intervention, such as functional training, sensory stimulation, strategy training and/or task repetition, ideally in the context of a clinical trial. It is more common in people with non-dominant hemisphere stroke (typically causing left-sided neglect) and those with hemianopia. Behavioural symptoms include bumping into objects on the affected side or only reading one side of pages in newspapers or books. There is insufficient high-quality evidence to recommend any specific interventions to increase independence. However, there is some very limited evidence that cognitive rehabilitation may have an immediate beneficial effect on tests of neglect (Bowen et al, 2013). B When assessing problems with spatial awareness in people with stroke, clinicians should use a standardised test battery in preference to a single subtest, and the effect on functional tasks such as dressing and mobility should be included. C People with impaired awareness to one side after stroke should: ‒ have the impairment explained to them, their family/carers and the multidisciplinary team; ‒ be trained in compensatory strategies to reduce the impact on their activities; ‒ be given cues to draw attention to the affected side during therapy and nursing activities; ‒ be monitored to ensure that they do not eat too little through missing food on one side of the plate; ‒ be offered interventions aimed at reducing the functional impact of the reduced awareness. Aphasia affects about a third of people with stroke, and can have a significant impact on the lives of individuals and their family/carers. Aphasia can affect mood, self-image, well-being, relationships, employment, leisure and social opportunities. Problems with communication can also occur following damage to the non-dominant hemisphere. Most trials investigate one aspect of management – impairment-based face-to-face treatment. Benefits were not evident at follow up but there are too few trials to conclude this with confidence. Drop-out rates may provide important information on the acceptability of therapy for people with aphasia at different time points after stroke. Overall the evidence from trials is not straightforward and must be interpreted with caution. Well-designed case series support the use of semantic and phonological therapies for anomia (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, 2005) and there is some evidence that communication partner training can improve participation (Simmons-Mackie et al, 2010). B In the first four months after stroke, people with aphasia should be given the opportunity to practise their language and communication with a speech and language therapist or other communication partner as frequently as tolerated. C After the first four months, people with communication problems after stroke should be reviewed to determine their suitability for further treatment with the aim of increasing participation in communication and social activities. This may involve using an assistant or volunteer, family member or communication partner guided by the speech and language therapist, computer-based practice or other impairment-based or functional treatment. D People with communication problems after stroke should be considered for assistive technology and communication aids by an appropriately trained, experienced clinician. E People with aphasia after stroke whose first language is not English should be assessed and provided with information about aphasia and communication practice in their preferred language. G People with persistent communication problems after stroke that limit their social activities should be offered information about local or national groups for people with aphasia, and referred as appropriate. Impaired muscular control affects speech intelligibility, which is usually described as slurred or blurred. Dysarthria is common in the early stages of stroke, and is often associated with dysphagia (swallowing difficulties, Section 4. Bowen et al (2012) included a planned subgroup of 66 people with dysarthria and Mackenzie et al (2014) was a feasibility study of 39 people. Mackenzie et al (2014) involved people with chronic dysarthria, and there was no difference in outcomes between individuals who received only speech practice and those who received speech practice and oro-motor exercises, although both groups improved over time. Participants were compliant with both interventions and many completed daily independent practice and reported an increase in confidence with treatment. There is little evidence to support the interventions in common use but there is some evidence of qualitative benefits (Palmer and Enderby, 2007). B People with dysarthria after stroke which limits communication should: ‒ be trained in techniques to improve the clarity of their speech; ‒ be assessed for compensatory and augmentative communication techniques. It is usually associated with damage to the non-dominant hemisphere, and requires careful separation from aphasia and dysarthria. Interventions such as syllable level therapy and metrical pacing have been studied and the use of computers to increase intensity of practice has been suggested. Evidence to recommendations Studies in apraxia of speech are often small and the most recent Cochrane review (West et al, 2005) found no trials. There has been one recent crossover trial (Varley et al, 2016) which compared self-administered computerised communication therapy with a sham computerised treatment for people with chronic speech apraxia. Improvements in spoken word production (naming and repetition) were greater for the intervention group after the six week treatment but limited to trained single words. B People with severe communication difficulties but good cognitive and language function after stroke should be assessed and provided with alternative or augmentative communication techniques or aids to supplement or compensate for limited speech. Incontinence of urine greatly increases the risk of skin breakdown and pressure ulceration. Incontinence of faeces is associated with more severe stroke and is more difficult to manage. Constipation is common, occurring in 55% of people within the first month of stroke, and can compound urinary and faecal incontinence. Incontinence has a detrimental effect on mood, confidence, self-image and participation in rehabilitation and is associated with carer stress. Incontinence is an area of stroke that has received little research interest, despite its substantial negative impact. It needs to be managed proactively to allow people with stroke to fully participate in their own care and recovery both in the acute phase and beyond. Evidence to recommendations A 2013 review of bowel management strategies (Lim and Childs, 2013) identified three small studies of varying quality, and concluded that the evidence was limited but a structured nurse-led approach may be 67 effective. In a review of therapeutic education for people with stroke, Daviet et al (2012) concluded from small non-randomised studies that a nurse-targeted education programme may improve longer term continence. A small study by Guo et al (2014) examined the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the treatment of urinary incontinence over six months and found an improvement in nocturia, urgency and frequency. B People with stroke should not have an indwelling (urethral) catheter inserted unless indicated to relieve urinary retention or when fluid balance is critical. C People with stroke who have continued loss of bladder and/or bowel control 2 weeks after onset should be reassessed to identify the cause of incontinence, and be involved in deriving a treatment plan (with their family/carers if appropriate). The treatment plan should include: ‒ treatment of any identified cause of incontinence; ‒ training for the person with stroke and/or their family/carers in the management of incontinence; ‒ referral for specialist treatments and behavioural adaptations if the person is able to participate; ‒ adequate arrangements for the continued supply of continence aids and services. D People with stroke with continued loss of urinary continence should be offered behavioural interventions and adaptations such as: ‒ timed toileting; ‒ prompted voiding; ‒ review of caffeine intake; ‒ bladder retraining; ‒ pelvic floor exercises; ‒ external equipment prior to considering pharmaceutical and long-term catheter options. E People with stroke with constipation should be offered: ‒ advice on diet, fluid intake and exercise; ‒ a regulated routine of toileting; ‒ a prescribed drug review to minimise use of constipating drugs; ‒ oral laxatives; ‒ a structured bowel management programme which includes nurse-led bowel care interventions; ‒ education and information for the person with stroke and their family/carers; ‒ rectal laxatives if severe problems persist. F People with continued continence problems on transfer of care from hospital should receive follow-up with specialist continence services in the community. In a large survey of long-term stroke survivors half of the respondents reported fatigue and 43% of those with fatigue said they had not received the help they needed (McKevitt et al, 2011). The most common features of fatigue are a lack of energy or an increased need to rest every day, but fatigue is characteristically not relieved by rest. Both mental and physical activity can cause fatigue, and some people are affected more by one than the other. Many people with stroke have to make a greater effort to carry out their activities and this explanation can provide reassurance, as can the information that for many people fatigue decreases over time. Other factors associated with fatigue include side-effects of medication, disturbed sleep as a result of pain (Section 4. Fatigue can be assessed by the routine use of a structured assessment scales (Mead et al, 2007). Management strategies include the identification of triggers and re-energisers, environmental modifications and lifestyle changes, scheduling and pacing, cognitive strategies to reduce mental effort, and psychological support to address mood, stress and adjustment.

Aggrenox caps 25/200mg for sale. SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS OF GROUP B STREP FACTS.

References

- Bagshaw SM, Laupland KB, Doig CJ, et al. Prognosis for long-term survival and renal recovery in critically ill patients with severe acute renal failure: a population-based study. Crit Care. 2005;9:R700-R709.

- Staab ME, Nishimura RA, Dearani JA: Isolated tricuspid valve surgery for severe tricuspid regurgitation following prior left heart valve surgery: Analysis of outcome in 34 patients, J Heart Valve Dis 8:567-574, 1999.

- Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4210-4221.

- Seiler L, Rump LC, Schulte-Monting J, et al: Diagnosis of primary aldosteronism: value of different screening parameters and influence of antihypertensive medication, Eur J Endocrinol 150(3):329n337, 2004.

- Le Trong I, Aprikian P, Kidd BA, et al: Structural basis for mechanical force regulation of the adhesin FimH via finger trap-like beta sheet twisting, Cell 141:645n655, 2010.